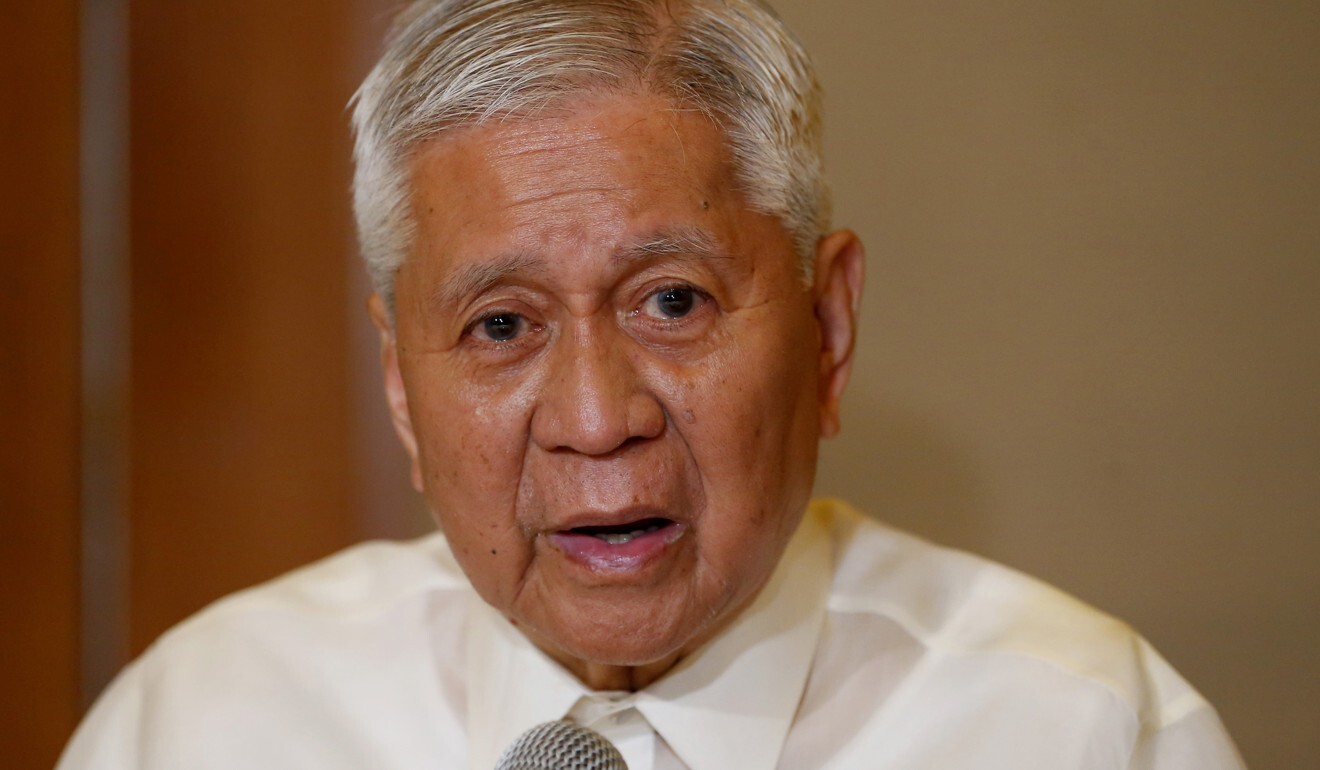

South China Sea: Beijing rushing code of conduct to undermine 2016 Hague ruling, claims Philippines’ Del Rosario

- Former foreign secretary and other experts allege Beijing has ulterior motive in claiming progress in long-running talks, and say final agreement is not likely this year or next

- Critics say two provisions China placed in the draft code will compromise Southeast Asian nations’ ability to partner foreign firms in military exercises and exploitation of energy resources. But some say compromise is needed

Talks on a code of conduct for the sea, where China and various Asean member states have several overlapping territorial disputes, have been going on for years, but appeared to have moved forward this month when Beijing claimed all sides had agreed to part of the text.

But Del Rosario and other experts taking part in Thursday’s lecture poured cold water on any suggestion of a breakthrough, saying the code was not likely to be finalised either this year or next.

Among the biggest obstacles, Del Rosario said, were suspicions that Beijing – which had previously delayed the talks for years on end – “appears to be rushing the conclusion”.

Del Rosario said this was because “China now sees the code of conduct as a way to undermine the 2016 ruling” by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. That ruling, in a case brought against China by the Philippines, rejected Beijing’s territorial claims to more than 90 per cent of the waterway.

Del Rosario’s talk, which was sponsored by the Carlos P. Romulo Foundation for Peace and Development and the Ateneo de Manila University, was timed to mark Asean’s 52nd founding anniversary.

03:23

The South China Sea dispute explained

Ian Storey, a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore who also spoke at the event, agreed with Del Rosario’s analysis and warned Asean’s credibility was on the line.

Storey pointed out that negotiations on the text of the code began only in 2014, about a year after Manila filed the case for arbitration.

In 2017, about a year after Manila won the case, the code of conduct negotiations sped up and by 2018 the parties had produced a single draft negotiating text that will be used in future negotiations.

Storey said the negotiating text included two provisions, introduced by China, that were “deeply troubling, that not only undermine the arbitral tribunal ruling but also violate the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea [UNCLOS]”.

The first of these provisions was that joint development of energy resources in the South China Sea should be restricted to partnerships between Chinese and Southeast Asian companies, to the exclusion of foreign firms.

Is Southeast Asia waking up to the need for unity in South China Sea?

Storey said this “would undermine the right of coastal states” to partner foreign companies in exploiting the resources of their own exclusive economic zones.

The second provision put a similar limit on joint military exercises in the sea: while Asean members and China could hold joint exercises between themselves, if any external country wanted to take part, the prior consent of all 11 parties (China and the 10 Asean states) would be required.

Storey said the second provision would effectively give “China a veto over foreign military activities in the South China Sea”.

Storey urged Asean to remove these two provisions, which he said were aimed at legitimising China’s territorial claims and undermining Southeast Asian countries’ “defence relations with extra-regional powers”.

He added that given the complexity of the issues, “I don’t think we can realistically expect the code to be signed in 2022, more likely in 2025.”

Jay Batongbacal, director of the University of the Philippines’ Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea, agreed. He said finalising the code soon was “not likely” since agreement so far had been “limited to the preamble”.

Time to compromise?

Malaysian analyst Ngeow Chow Bing said Asean would have to make compromises if it wanted a code of conduct. He said Malaysia was committed to such a code, though it was a “least bad option” and likely to be flawed.

Ngeow, the director of the Institute of China Studies at the University of Malaya, said Asean states had to make some kind of compromise to break the impasse because asking China to comply with the arbitral ruling was unlikely to work.

China has said it neither accepts nor recognises the 2016 ruling.

It “would be almost impossible to ask [Beijing] to retreat all the way back to Hainan and give up all their claims”, said Ngeow, referring to the island off the south coast of mainland China.

Ngeow said he saw the Malaysian government maintaining a position of flexibility because it viewed the code of conduct as a building block that would evolve over time.

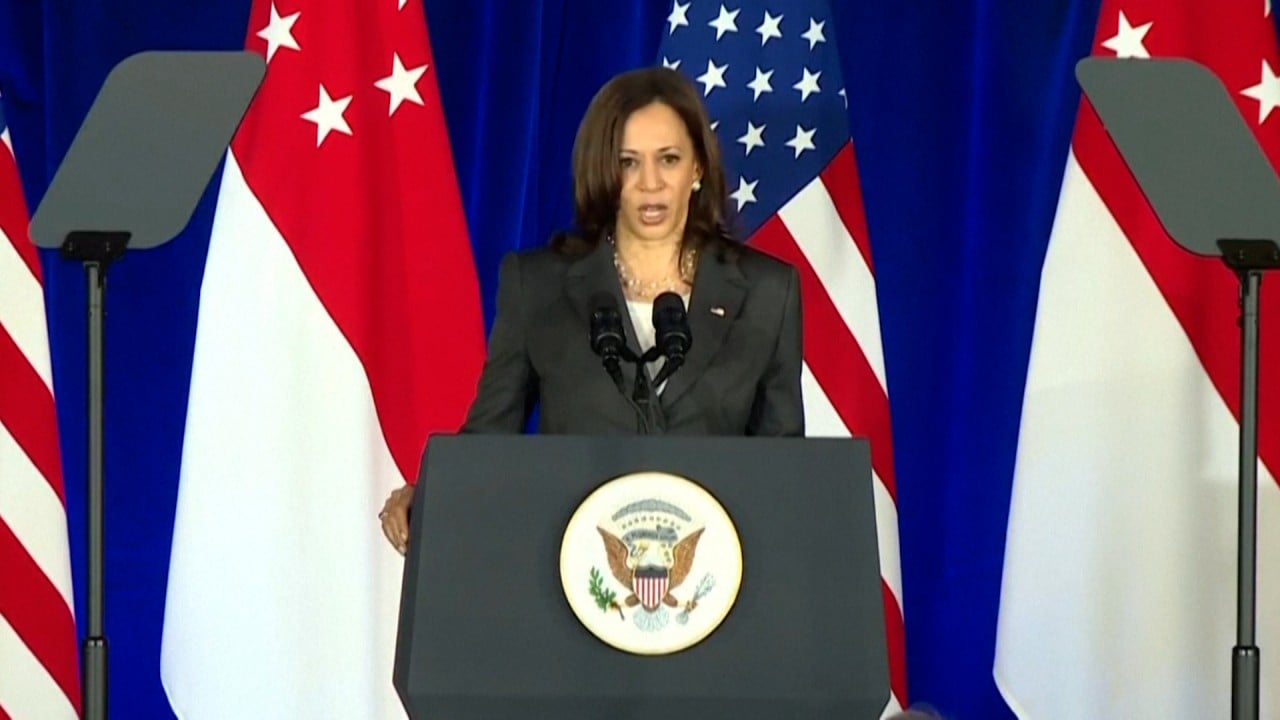

01:19

US Vice-President Kamala Harris: China continues to ‘coerce’ and ‘intimidate’ in South China Sea

Political science professor Alma Salvador, who teaches international relations at the Ateneo de Manila University, said given the challenges of the code of conduct negotiations Asean countries should go after the “low lying fruit” of agreements on fishing, the environment and a safety mechanism to manage incidents at sea.

Former Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans said Asean countries should not expect the United States to bear the full burden of maritime security in the region, even though it was seeking to counter China’s influence.

Evans said “the fiasco of the Afghanistan withdrawal” had highlighted the risks of relying solely on the US to keep the peace.

“I don’t think the United States will abandon its general commitment to the Indo-Pacific any time soon, but I don’t think any of us can assume that it would do all the heavy lifting itself. I don’t think any of us can assume that there is anything automatic about the support the allies and partners of the US can expect if we get into trouble,” Evans said.