Money woes or curbing dissent? Singapore’s academic community bemoans Yale-NUS college closure

- The city state’s first liberal arts institution, which was set up in 2011, will be merged with another programme to form a new entity

- While some students believed campus activism played a role in the decision, a board member cited ‘financial unsustainability’ and insisted the move was to make liberal arts education more inclusive

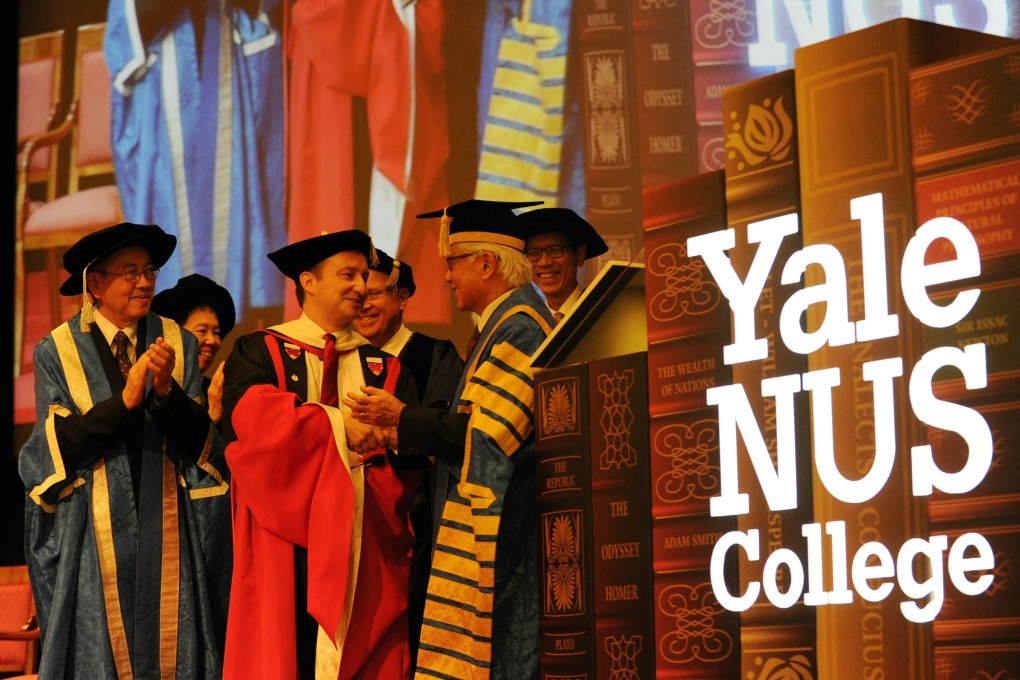

Primarily funded by the Singapore government, the college was hailed as epoch-making when it admitted its first students in 2013 with a double barrelled name that featured an Ivy League school and the island nation’s oldest university.

Yale, founded as a divinity school in 1701, said at the time the new college in Singapore would be the “first new college to bear the Yale name in 300 years”.

Eight years on, that experiment is coming to an end under controversial circumstances.

On August 26, students of the college were told that classes the next day would be cancelled and an online town hall would be held instead.

Administrators told students during that session that the National University of Singapore had decided to merge Yale-NUS College with another programme – the University Scholars Programme (USP) – to create a new college.