Two decades after 9/11: was Southeast Asia’s support of the US war on terror worth it?

- The region largely welcomed greater US cooperation after 9/11, with the war on terror helping some Asean states to further their own agendas

- But the US failed to make the most of the engagement, experts say, and its torture of detainees left mixed messages about the values it was seeking to promote

The deadly terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, prompted an outcry from around the world: “We are all Americans.” Washington’s policies realigned around fighting terrorism and bilateral relationships strengthened or crumbled depending on where other governments stood. In the sixth in a series about the legacy of September 11, Bhavan Jaipragas looks at Southeast Asia’s support of the US-led global counterterrorism effort.

Instead, much like the present-day top US government officials, Powell offered repeated assurances that the US was in fact a “Pacific nation” committed to advancing mutual interests by maintaining its economic and strategic presence in the neighbourhood.

These pacts were exceptions that did not serve US interests, but otherwise “people will see that we do want to participate in the larger world community”, Powell said.

Just how convinced Powell’s counterparts in Hanoi were by his charm offensive is unclear; but when the administration launched its “global war on terror” soon after the World Trade Center attacks, much of the region – including US sceptics – expressed a degree of endorsement for the effort.

The use of torture and CIA ‘black sites’ … came to stand as a symbol of Washington’s violations of the very same principles it expected others to adhere

With an eye on the threat posed by Islamist militants at home, the Philippines displayed the most enthusiastic reaction. President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo almost immediately granted the US access to airbases and other facilities. In exchange, the Bush administration made some US$100 million of military aid available when she visited Washington two months after September 11.

Singapore and Thailand, hosts of minor US military facilities, also offered their quiet backing, while Muslim-majority neighbours Indonesia and Malaysia tempered their sympathy for America’s losses by warning that US reprisals should not target Islam generally.

By and large, the region welcomed greater cooperation with the US in the months and years immediately after September 11, even if the dealings were mainly confined to security matters.

The legacy of the 9/11 terror attacks, 20 years on

Michael Vatikiotis, Asia director at the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, said the severity of the attacks meant cooperation “was swiftly established and reliably executed”.

The immediate outbreak of Islamic militancy in the region – starting with the 2002 Bali bombings – helped to “focus minds in the region on close cooperation with the US”.

“There was little hesitancy or argument – the US and certain Asean countries needed each other to contain the terror threat,” Vatikiotis said.

Could the US have capitalised on this milieu to broaden engagement in the region?

Asked to offer their thoughts on the legacy left by the US-led global war on terror in Southeast Asia, diplomatic observers who spoke to This Week in Asia suggested Washington failed to fully take advantage of opportunities to fortify its presence in the region during this period.

“The downside of this increased focus on terrorism was that it caused the US to adopt a narrow view of American interests and miss other opportunities for increased diplomatic engagement with Southeast Asia as a grouping,” said Murray Hiebert, a Southeast Asia expert at Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies.

What is the ‘Indo-Pacific’ and why does the US keep using this term?

03:25

What has Kamala Harris achieved during her week-long trip to Southeast Asia?

Winners and losers

Observers noted, nonetheless, that regional states would look back at the past two decades acknowledging that in the security realm they had reaped a net benefit from the global war on terror.

The consensus view was that the Philippines and Indonesia were the top beneficiaries of Bush’s post-September 11 call to arms.

Hiebert pointed to the inroads Manila had made in dealing with Islamist insurgencies in the restive Mindanao region with US help, as well as America’s key role in aiding local authorities to liberate the city of Marawi from a months-long occupation by pro-Islamic State militants.

Vatikiotis noted that America’s efforts in Indonesia were largely in the background with intelligence gathering and training for the task force set up to go after Islamist militants.

Thailand, which at the time was dealing with an intensified insurgency in its largely Muslim southern region, was also rewarded for its support of the war on terror. In October 2003, Bush declared Thailand a major non-Nato ally – an elite status that gave it priority access to US military exports.

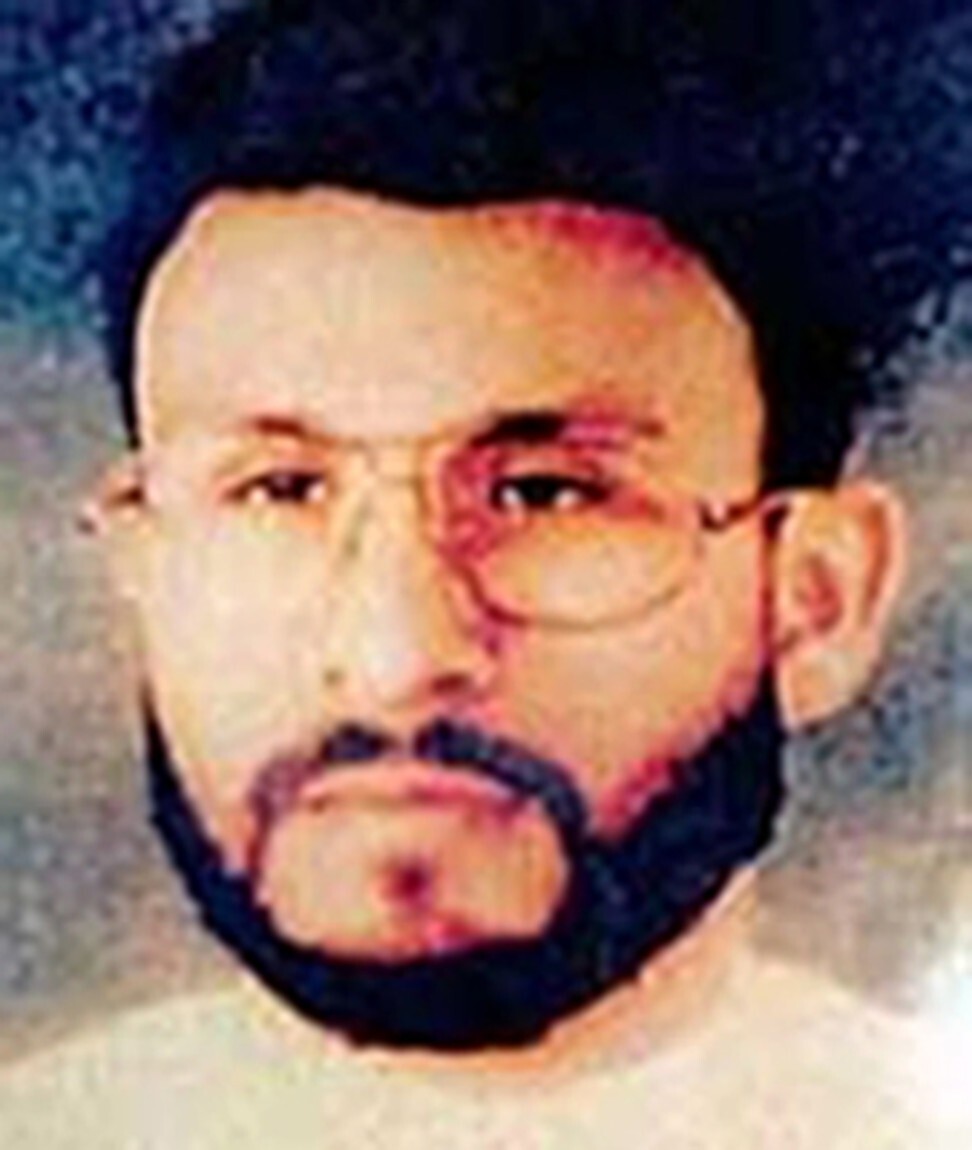

That development came months after Thai and US forces captured Hambali, the Indonesian mastermind of the 2002 Bali bombings, in the Thai city of Ayutthaya.

Thailand’s track record showed it was an “eager participant” in the war on terror with the Southern insurgency seen as among the reasons for this enthusiasm, said Paul Chambers from the Centre of Asean Community Studies at Thailand’s Naresuan University.

Chong Ja Ian, an Asian foreign policy scholar at the National University of Singapore (NUS), said he did not see the “benefits breaking down across states”.

Rather, regional states in general gained from using the US-led global counterterrorism effort to “gain prominence” over “real and potential domestic challengers”, he said.

Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand were able to diminish the roles of groups like Jemaah Islamiah, Abu Sayyaf and Islamic State that were deemed “extremist”, Chong noted.

Singapore, which did not experience the same acuteness of security concerns – though it has over the years held alleged militants in detention without trial – reaped benefits too, as it overtly backed the Bush administration.

Taliban’s return ‘boosts morale’ of militant groups in Southeast Asia

“The war on terror enabled Singapore to build on already extensive military and security cooperation with the United States, including deploying forces to Afghanistan and Iraq,” Chong said.

Hunter Marston, a non-resident WSD-Handa fellow with the Honolulu-based Pacific Forum think tank, said Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar did not gain much from Washington’s war on terror as they didn’t face the same problems from Islamist militants as their Southeast Asian neighbours.

He added that in the case of Vietnam and Laos, expanded security cooperation was limited by the fact that they were communist states, which the “US bombed and fought in the recent past”, while Myanmar was at the time under a military dictatorship and was the target of US sanctions.

Dark legacy

The US-led war on terror may have allowed Southeast Asian nations to add bulk to their security apparatuses to fight Islamic militancy, but that development more often than not hurt the region’s already precarious state of civil liberties, the experts said.

Chong noted that generally, there was “less restraint on the use of force on the part of the state, including detention without trial”.

In the Southeast Asian context, one particularly repulsive aspect of the post-September 11 years was Thailand’s hosting of a secret “black site”, where detainees were subject to so-called enhanced interrogation techniques.

The Thai site, whose existence Thai administrations have denied, was the first such base set up by the US Central Intelligence Agency.

An executive summary of a confidential, 6,000-page report by the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on the abuses named a site called Detention Site Green that major media outlets have identified as located in Thailand.

The torture techniques used on him did not produce actionable information.

A film dramatising the CIA’s use of torture on Abu Zubaydah and at least 38 others – as well as the US Senate Select Committee’s subsequent roadblock-ridden investigations – was released in 2019.

A total of 119 detainees were held in CIA black sites between 2002 and 2008, and at least three – including Abu Zubaydah – were subject to waterboarding, a torture technique that simulates drowning.

At least five were subjected to “rectal rehydration” – being forced-fed rectally – and at least one detainee, Afghan national Gul Rahman, died in custody, likely due to hypothermia, in 2002.

Hambali, who is currently standing trial, also claims he was tortured in detention.

Previously classified CIA guidelines reveal in-house medical personnel were complicit in torture

Writing in The Diplomat magazine this month, NUS professor Bilveer Singh said this aspect of the global war on terror caused Washington’s moral standing in the region to decline.

“The use of torture and CIA ‘black sites’ … [and] the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay came to stand as a symbol of Washington’s violations of the very same principles it expected others to adhere,” Singh wrote.

Analysts suggested this mixed legacy, coupled with the chaotic US pull-out from Afghanistan, would mean that Asean would look back at the last two decades with more questions than answers as to the true intent of America’s global presence.

This is despite the rhetoric by a long line of US officials, from Powell to vice-president Harris.

“Generally speaking, regional countries will remember this period as they view US policy more generally: with deep ambivalence,” said Marston, a Southeast Asia scholar at the Australian National University.

“During this time, Asean states welcomed renewed US attention to the region, even if it was misplaced or overemphasised counterterrorism,” he said. “But by and large, regional states have long seen Washington as distracted and more interested in its own agenda than in listening to regional views and interests.”

Singh of NUS wrote that taking into account the fact of the Biden administration’s Afghanistan withdrawal, the Taliban’s return to power and the continued existence of Islamic militancy in Southeast Asia, “it is difficult to conclude that the global war on terror was successful”.