Philippine presidential race: why Bongbong’s bid may be sunk by a law his dictator father Ferdinand Marcos Snr made in the 1970s

- Ferdinand Marcos Snr brought in a law banning any government official convicted of tax fraud from holding public office. Decades later, that never-before-tested law has come back to bite his son

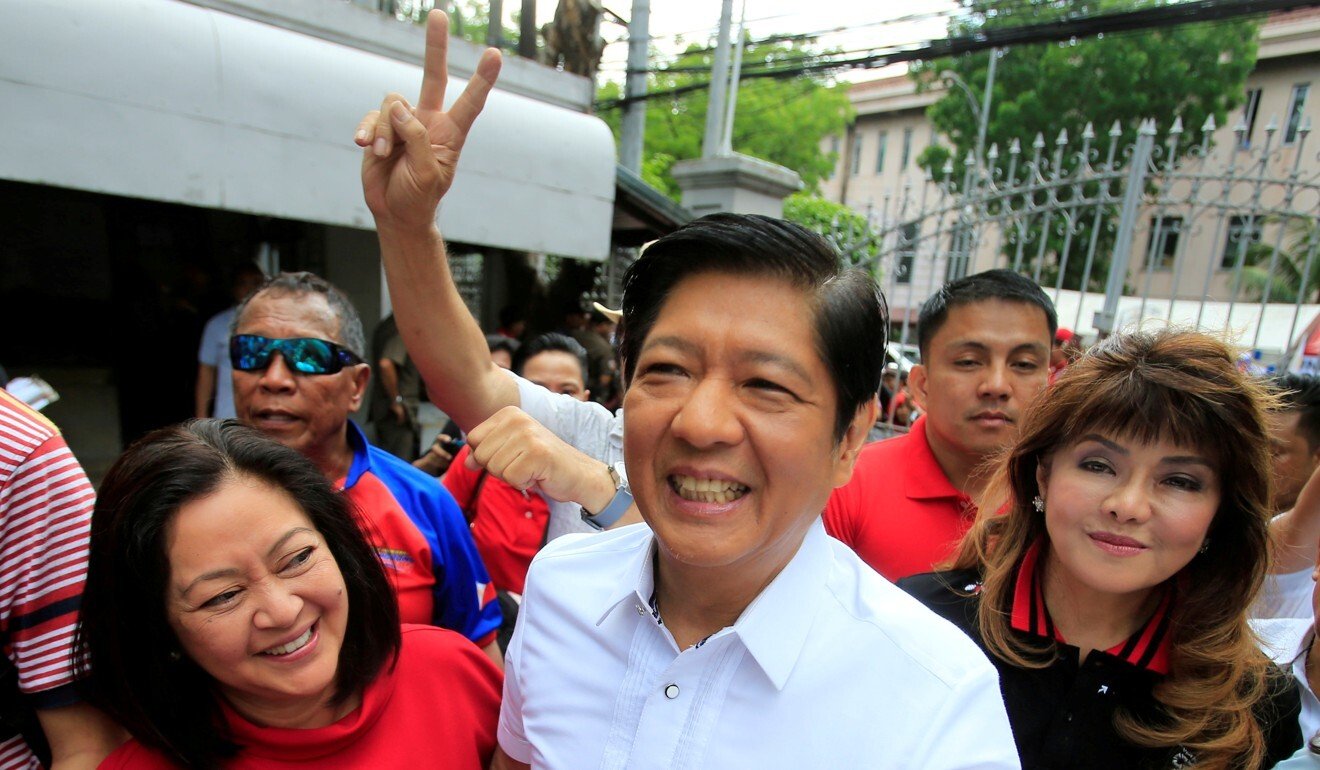

- Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jnr was found guilty of tax fraud on his return from exile in the 1990s, giving hope to his opponents that his presidential ambitions could be thwarted. But the Marcos camp is not giving up so easily

Ferdinand Marcos Snr had used his dictatorial powers in the 1970s to write a special clause into the National Internal Revenue Code banning any government official convicted of tax fraud from holding public office.

The law remains in force today – though the clause has never been used – and could derail the presidential ambitions of Marcos Jnr, who was found guilty of tax fraud on his return to the Philippines in the 1990s following the family’s exile in Hawaii.

“The irony is that it was Bongbong’s father who introduced the special disqualification clause and it is Bongbong who will be the first to suffer under that provision,” retired Supreme Court associate justice Antonio Carpio told This Week in Asia on Thursday.

“The son will be the first to suffer because of laws made by his father. That’s the karma of the family,” he added.

Marcos Jnr filed his papers to run in the 2022 election on October 6. Almost a month later, on November 2, victims of Marcos Snr’s regime filed a 57 page petition with the Commission on Elections demanding Marcos Jnr be disqualified due to his conviction.

Asked why the issue of the conviction had not been raised earlier, Carpio said that “everybody had forgotten about it”.

The Marcos camp, however, has accused “yellow wannabe political assassins” of using “gutter politics” to take him out of the race. It argues that, while Marcos Jnr was found guilty of tax fraud, the size of his fine and the fact he eventually managed to avoid serving a jail term means that, under a separate law, the disqualification clause does not apply to him.

Marcos himself has been defiant, saying: “I am not afraid. I won’t retreat. I won’t withdraw.”

A law unto themselves

The National Internal Revenue Code was created by the elder Marcos in 1977. Section 252 of the law specifies that once a public officer or employee is convicted of violating any section of the Code, “the maximum penalty prescribed for the offence shall be imposed and, in addition, he shall be dismissed from the public service and perpetually disqualified from holding any public office, to vote and to participate in any election”.

About a month before the Marcos family fled the Philippines for Hawaii in February 1986, having been forced into exile by a bloodless People Power uprising, the dictator had amended the code to further emphasise the disqualification clause.

“Marcos really set a very high standard for government officials except for himself and his family,” Carpio said. “But they themselves were above the law” and never thought they would be ousted from power, he added.

Large scale tax fraud was among the many accusations levelled at the Marcos family after the fall of the dictator, whose reign – which included a lengthy stint under martial law – was infamous for corruption and brutality. In 2003, the Supreme Court ruled that Marcos Snr and his wife Imelda were guilty, among other offences, of tax fraud and ordered their Swiss Bank deposits of nearly US$700 million to be turned over to the government.

The trial of Marcos Jnr

Marcos Snr died in Hawaii in 1989. Two years later, his only son returned to the Philippines.

Arrest warrants for tax fraud awaited him at the airport. He quickly posted bail, waived his right to a pre-trial hearing and was arraigned on December 9, 1991, pleading not guilty.

On July 27, 1995, regional trial court judge Benedicto Ulep found Marcos Jnr “guilty beyond reasonable doubt” of violating the National Internal Revenue Code for tax deficiencies totalling 8,504.23 pesos (US$168), plus surcharge and interest, and not filing income tax returns while he was governor of his home province of Ilocos Norte from 1982 to 1985. (To put the figure in perspective, the daily minimum wage of the time in Manila was 37 pesos, or 32 pesos in plantations).

Marcos Jnr had claimed in court that he never received a single cent of his salary as governor because he had all the money placed “in a bank in the form of scholarship foundation for the poor”. He also claimed that his staff, including Paula Pastor, had never told him he had to file tax returns and he could therefore not recall filing any.

However, Paula Pastor testified that she had opened a bank account for Marcos Jnr in his name – not in the name of a foundation – and that all of his salary was deposited into this account.

‘Bongbong’ runs for president, sparking anger from his father’s victims

The court was also told that withdrawals had been made from this account while Marcos Jnr was exiled in Hawaii. Marcos Jnr said he did not know who had made these withdrawals and insisted he had not authorised anyone to do so on his behalf.

Unimpressed, the judge sentenced Marcos Jnr to a total of nine years in jail and ordered him to pay 72,000 pesos to cover the tax deficiencies plus “penalties, interests and surcharges” imposed by the Bureau of Internal Revenue.

Marcos never served a single day in jail. He immediately went to the Court of Appeals, where three judges removed the jail term from the sentence on the grounds he had not been given enough time to refute the charges. They also acquitted him of the charge of tax deficiencies, though ruled he should still pay the 72,000 pesos.

However, the Court of Appeals did find that he was “guilty beyond reasonable doubt” of failing to file his income tax returns for three years.

Marcos then went to the Supreme Court to argue his case, but later withdrew and the appeal court’s ruling “became final and executory” in 2001, Carpio said.

Carpio said he did not know whether Marcos ever paid the 72,000 pesos.

In the clear after all?

Still, the Marcos camp believe their man could yet be cleared to run. Buoying their optimism is another law, the Omnibus Election Code, which came into effect in 1985 and stipulates that the ban on public office applies only to those convicted of a crime “involving moral turpitude” with a sentence of more than 18 months in jail.

Victor Rodriguez, a spokesman for Marcos Jnr, has argued that the “small” fine imposed by the tax bureau, and the charge of non-filing of income tax returns do not amount to moral turpitude. He has also pointed out that the jail sentence for Marcos Jnr was dropped by the Court of Appeals.

Robredo to battle Marcos for Philippine presidency

The decision on whether Marcos Jnr can run or not now appears to lie with the Commission on Elections, though any ruling it makes could still be appealed at the Supreme Court.

Carpio, the retired justice, said he was confident that the various laws did not contradict each other and that Marcos Jnr’s presidential bid would therefore be found illegal.

He said that if that were indeed the case the only thing that could save Marcos Jnr’s bid would be for President Rodrigo Duterte to erase his tax convictions through a presidential pardon.