Ukraine war: Malaysia diplomat’s remarks on allowing Russia semiconductor exports raise fears Kuala Lumpur could be hit by sanctions

- Kuala Lumpur’s envoy to Moscow suggested Malaysia would consider ‘any request’ from Russia for the sale of semiconductors

- A deal with Russia could potentially see Malaysia blacklisted for breaching sanctions imposed on Moscow for its invasion of Ukraine

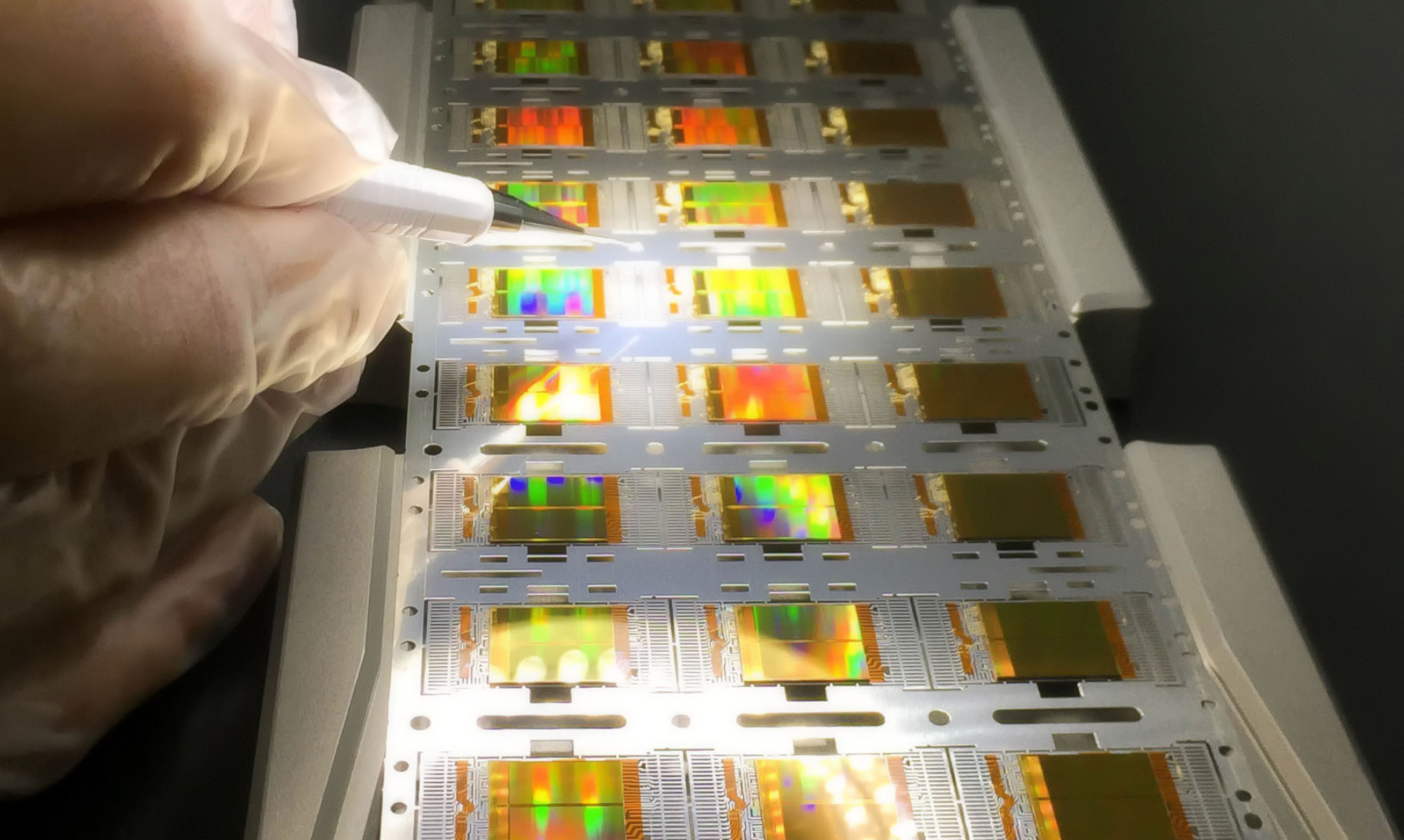

Malaysia has long had a little-known but crucial role in the global semiconductor industry. It is one of the main sites for assembly, testing and packaging for the likes of Toyota, Ford, General Motors and Skoda Auto.

Noting that Malaysia’s industries were “market oriented” Chandran said he was “quite sure that any request from the Russian side regarding the supply of such products will be considered”.

International relations expert Hoo Chiew Ping said that while Malaysia is indeed a major fabricator of electronics and semiconductors, it might not necessarily own the intellectual property for the parts, which could belong to US and Japanese companies who are major investors in the Malaysian market.

US sanctions pressure on Russia shows geopolitics now trumps economics

“Malaysia can be blacklisted for breaching the sanctions and IP rights. This will have dire consequences for its semiconductor manufacturing and export economy,” said Hoo, an expert on sanctions.

“When [the ambassador] suggested that Malaysia ‘would’ consider to sell semiconductors to Russia, however, it puts Malaysia at risk when other countries are banning trade with Russia,” said Tunku Mohar Tunku Mokhtar, a Malaysian political expert. Mokhtar believes the ambassador was just being diplomatic in his response, “but in doing so, it also shows opportunistic gestures since Taiwan has banned the export of such products to Russia”.

Understanding the severity of Malaysian companies being slapped with such action, geostrategic expert Azmi Hassan hopes the ambassador’s comment was just “to be nice to [the] Kremlin” as part of his capacity as Malaysia’s envoy.

“This is not the right time to conduct new businesses with Russia,” he said.

With the war in Ukraine dominating the news, Azmi said the diplomat should be more careful with what he says as it “would not look good for Malaysia”.

His reaction is echoed by Hoo.

“As Malaysia is trying to implement our foreign policy framework for post-pandemic recovery, we need to look after our reputation as a destination for foreign investment by threading these issues carefully,” she said.

But any past goodwill from Washington could be undone by Chandran’s interview, which was shared by Russian state-owned news media as well as the Russian embassy in Kuala Lumpur, and reflects Moscow’s intensified public relations, according to a report on pro-Russian sentiments by ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

Ukraine crisis: why Western sanctions are a double-edged sword

Both experts sense that many felt the need to support Russia, or at the very least, the invasion as a way to maintain “pragmatic neutrality” and condemned the act of directly dressing Russia down, which they saw as a breach of Malaysia’s “neutral position”.

“The rationale was that since Malaysia was not a party to the war, it should abstain from any verbal involvement in it,” they said.

The ambassador’s interview was received with mixed reaction by the Malaysian public, with some expressing disgust at the government for its penchant for “siding with dictators”.

Others however welcomed it, asserting Malaysia’s right as an independent nation to befriend whoever it chooses.

“Malaysia feels that this is a European thing, so we don’t want to get involved. It is also a superpower thing, nothing to do with the Muslim world,” said Chin.