Philippine election: What does a Marcos Jnr presidency mean for Asean and democracy in the region?

- Eyes will be on whether his administration follows Duterte’s pivot away from the US in favour of China, and his approach to the South China Sea dispute, analysts say

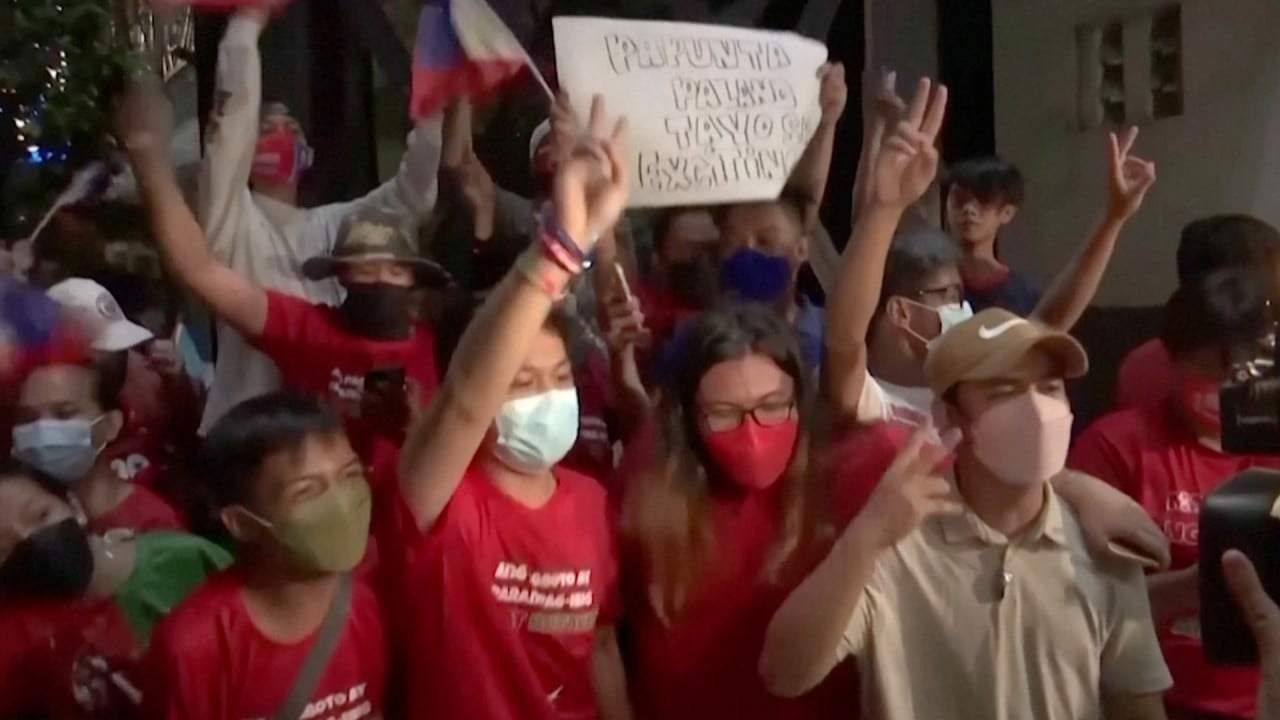

- Marcos Jnr’s victory also contributes to ‘regional democratic regression’, observers say, not least due to his refusal to admit his family’s wrongdoings and his campaign’s use of fake news to win the election

Marcos Jnr is the son and namesake of the late Philippine dictator whose family has been synonymous with kleptocracy in Southeast Asia for decades.

The senior Marcos was ousted by a “people power” revolution in 1986 following two decades of rule, during which he was accused of egregious human rights abuses and the plundering of more than US$10 billion from the country’s coffers. While some US$3 billion are said to have been recovered, about two dozen lawsuits are still pending to obtain another US$2 billion.

“There will be a fresh start,” Arugay said. “He can engage the US without the negative historical and personal baggage that Duterte had, and he can also ask China to negotiate with him.”

Manila “has been getting closer to the US in terms of defence cooperation, while China remains an important actor in the Philippines’ domestic economy”, Dermawan said, adding that maintaining Asean’s unity in the Indo-Pacific required the collective voices of its member states.

The Marcos family’s history – and outstanding US litigation against them – could complicate relations between Washington and Manila

“(It) would help Marcos score political points at home but perhaps create friction with some of Asean’s more pro-China members,” Dunst said, adding that Marcos Jnr was expected to run a more professional and predictable administration than predecessor Duterte, which could smoothen cooperation with Asean partners.

After taking office in 2016, Duterte pursued warmer ties with Beijing, setting aside a long-standing territorial feud over its claims in the South China Sea in exchange for billions of dollars of aid, loans and investment pledges.

Philippines’ Marcos sweeps to landslide win, in reversal of family’s fortunes

For now, a Marcos Jnr presidency is likely to spell continuity in the Philippines’ approach to regional politics, suggested Chong Ja Ian, an observer of China’s influence in Southeast Asia.

Marcos Jnr may wish to develop ties with China, he said, but may find complications in Beijing’s continued arming of reclaimed maritime features in the South China Sea and efforts to enforce its writ in the disputed waters. “That could spell continued momentum to develop security ties with the US.”

However, Dunst said the traditionally strong US-Philippines alliance had been “somewhat adrift” since Duterte took office, and Marcos Jnr may look to lean more towards Washington, especially given the popularity of the US among Filipinos.

Will Bongbong Marcos be the first Philippine president who cannot visit the US?

Yang Jinglin, an associate professor at the Center for China-Asean Studies at the Guangxi University for Nationalities, said Marcos Jnr was likely to “maintain a distance with the US and will continue with Duterte’s China policy, especially in the South China Sea”.

The incoming Philippine leader was likely to strengthen security cooperation within Asean, reduce military dependence on the US and seek to weaken the political influence of major powers within Southeast Asia, she said.

Asian democracy in peril?

Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, said Marcos Jnr’s victory was “terrible for democracy in the Philippines and adds to the regional democratic regression”.

“It shows impunity, there was never any real punishment for the Marcos family’s actions, and it is likely Marcos Jnr will further degrade Philippine democracy after Duterte,” he said, adding that the Marcos Jnr campaign appeared to have used disinformation as part of its election strategy.

Democracy has been in deficit in the region for a very long time

Arugay said Southeast Asian governments might have been more “uncomfortable” if rival Leni Robredo had won, judging from the democratic ideas that she represented. “Democracy has been in deficit in the region for a very long time,” he said.

“In the region, the Philippines used to be the last bastion of democracy,” he said. “That was taken away from us when we elected Duterte to power, and this will likely continue or might even worsen in the Marcos Jnr presidency.”

Arugay noted Marcos Jnr was not the only figure of concern. His running mate Sara Duterte-Carpio, the daughter of outgoing President Duterte, also secured a huge victory in the race for the vice-presidency. “Their alliance is the cartelisation of dynasties that is pretty much an existential threat to liberal democracy,” he said.

Is Bongbong Marcos’ win a sign of nostalgia for his father’s strongman rule?

The Asean Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) on Tuesday expressed concerns that the incoming Philippine administration may not include human rights in its agenda, given that Marcos Jnr had “systematically whitewashed the appalling human rights record of his father”.

Marcos Jnr and his camp had used social media to run large-scale disinformation campaigns during the presidential campaign, a strategy that enormously influenced the election outcome in a country with more than 92 million recorded social media users.

“The victory of the son of a dictator and the daughter of a human rights abuser, both of whom have staunchly defended the legacy of their fathers, do not bode well for the restoration of rule of law and respect for human rights in the country,” said Charles Santiago, APHR chairperson and a Malaysian parliamentarian.

On Tuesday, Marcos Jnr told the world to judge him based on his leadership, not his family’s past.

“Judge me not by my ancestors, but by my actions,” he said, according to a statement by his spokesperson Vic Rodriguez.

“This is a victory for all Filipinos, and for democracy,” spokesman Rodriguez said. “To those who voted for Bongbong, and those who did not, it is his promise to be a president for all Filipinos. To seek common ground across political divides, and to work together to unite the nation.”

Additional reporting by Reuters