50 years after Okinawa’s return to Japan from post-World War II US occupation, locals have no appetite to celebrate

- Locals say the US military presence has been the cause of numerous incidents of crime, environmental pollution and damage to the people of Okinawa

- 80 years since the end of World War II, locals say its time for the US to leave, stop work of a new base, and reduce the amount of American bases in Okinawa

Anger in Japan’s Okinawa as US bases blamed for Omicron spread

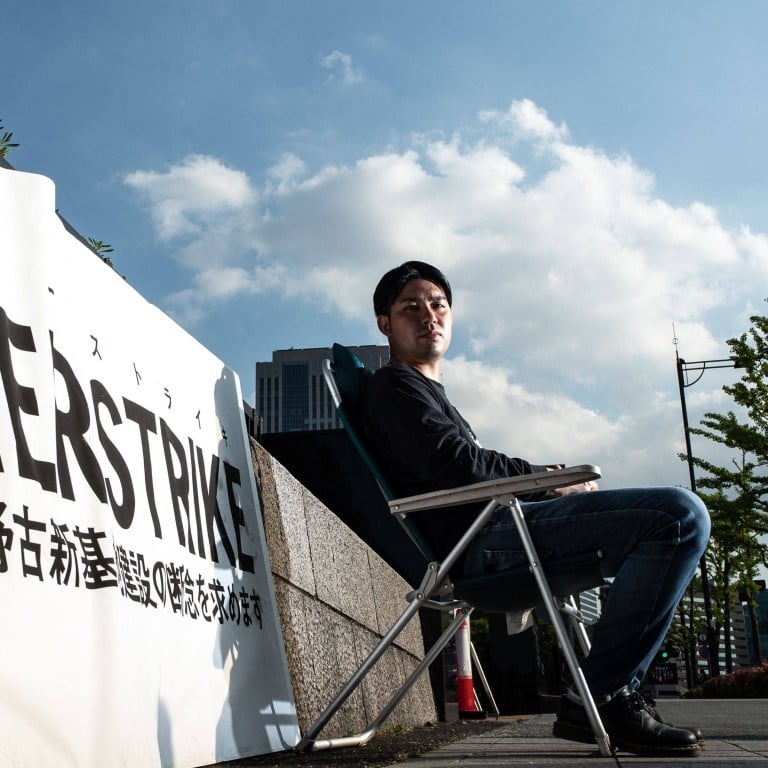

Jinshiro Motoyama is so incensed at how the voices of Okinawans have simply been ignored by political leaders in Tokyo and Washington that he began a hunger strike outside the Diet building in central Tokyo on May 9.

Motoyama has countless concerns about the plight of Okinawans but his one-man protest has one initial demand; a halt to the construction of a new military base on reclaimed land off the community of Henoko, in the north-east of the prefecture, to take over the functions of the US Marine Corps’ Futenma Air Station.

“My basic demand is the immediate termination of work on the new base at Henoko and a reduction in the total number of US bases in Okinawa,” said 30-year-old Motoyama, who is originally from the city of Ginowan in the prefecture but is presently completing a PhD at Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo.

“May 15 might mark the anniversary of the return of Okinawa to Japanese control, but local people do not see that as a reason to celebrate,” he told The Post. “The US military presence has been the cause of numerous incidents of crime, environmental pollution and damage to the people of Okinawa, yet the governments of Japan and the US have made no efforts to improve the situation.”

Five days into his hunger strike, Motoyama says he feels relatively healthy, but intends to listen to a doctor’s advice about how long he should continue his protest. But he is not optimistic that the Japanese government is listening.

“The defence minister, the chief cabinet secretary and the foreign minister have all come out and said that moving the US Marines to Henoko is the ‘only solution’ to the problem of Futenma. In 2003, then-US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said it was the most dangerous airbase in the world because it is right in the middle of the city,” he said. “So I don’t think they care very much about my hunger strike.”

Chinese aircraft carrier Liaoning sails near Japan’s Okinawa islands

Motoyama’s protest does, however, echo the position of the Okinawan Governor, Denny Tamaki.

Hugely popular for his willingness to stand up to the national government, Tamaki on Tuesday handed Prime Minister Fumio Kishida a written request that Tokyo do more to ensure the peace and prosperity of his prefecture. He also called on the national government to set up a forum for discussions with Okinawans about the future of the bases and finding a way to share the burden more equally across the nation.

An opinion poll conducted jointly by the Mainichi Shimbun and the Ryukyu Shimpo in the run-up to the anniversary determined that 69 per cent of Okinawans believed the concentration of US military facilities in the prefecture was “unfair”. Nationwide the figure was just 33 per cent. Critics say it shows residents of mainland Japan are relieved the bases are a long way from where they live and would oppose any transfer of US forces to mainland Japan.

Eric Wada, whose great-grandparents left impoverished Okinawa in 1903 to work in the plantations of Hawaii, says there are parallels between many of the islands of the Pacific that were colonised and still effectively remain under foreign control.

“We see it here, in Okinawa, Guam and elsewhere, with land taken under duress, colonial administrators coming in and keeping the local community under control through the education system and the economy,” said Wada, a professor at the University of Hawaii and an activist for Okinawans’ rights.

And while many Okinawans are unhappy at the problems they face, most are still at least reasonably satisfied with their day-to-day situations. That might change, Wada points out, which could trigger support for what is at present a very nascent movement for independence of Okinawa.

And while Motoyama has little confidence things will change for the better for the Okinawan people in the immediate future, he still holds out hope for further down the line.

“I hope that gradually, more of the bases will be returned to the Okinawan people who own the land,” he said. “I hope there will be fewer incidents involving the US military and less pollution of the islands.”

But in a time of worsening tensions and great power-rivalries in the Asia-Pacific region, he also has an overpowering fear.

“The worst possibility would be a conflict in the region as that would probably put Japan and the US on one side and China on the other, and with so many US bases on Okinawa, it would immediately become a target,” he said. “I have friends and family there and the last thing I want is for missiles to be aimed at the US bases. We need negotiations with the countries in the region to build our economies and share our cultures and have peace in East Asia.”