Ahead of historic US-Pacific meeting, climate change and China loom large, say analysts

- President Joe Biden will host first-ever summit with Pacific leaders in Washington next month, amid Beijing’s growing regional influence

- The islands ‘would be happy’ to work with either, say analysts, given the existential threat faced as the planet heats up and sea levels rise

“(The) meeting will be a historic opportunity with the United States and Pacific island countries to hear and listen, the Pacific way,” she said.

But while she talked of climate change being an “existential” threat to the Pacific, no concrete policies or aid schemes were announced during the trip, analysts noted.

Ying Zhu, director of the Australian Centre for Asian Business at the University of South Australia, said that without tangible outcomes, “it is hard to get real strong commitment from the Pacific islands towards the US”.

He said the region would show greater support if Washington could help Pacific nations tackle climate change, their most significant worry.

They are facing many related issues, ranging from rising sea levels, coastal flooding and erosion, to overfishing and the failure of subsistence crops.

While Sherman’s trip was timed to commemorate important battles during the second world war, other senior members of the US administration have also travelled to the Pacific this year, coming on the heels of similar visits by Chinese officials.

By April, the US had provided over US$32 million in funding to support the Pacific’s coronavirus response and pledged US$1 million in international disaster help.

The flurry of competing visits have prompted wariness by Pacific leaders on Washington’s agenda in engaging with the region.

Marc Lanteigne, associate professor at the University of Tromsø in Norway, said Washington had taken several steps in the right direction with its Pacific policies, including attempting to reverse “the de facto exclusion of the Pacific Islands region from American diplomacy” during former president Donald Trump’s administration.

Recent promises to open more US embassies in the region was a positive sign, Lanteigne said, referring to the bipartisan effort to introduce legislation aimed at establishing three new embassies in Vanuatu, Kiribati and Tonga.

“However, there will be a lot of pressure on the US government to follow through on these pledges as soon as possible,” Lanteigne said, noting that previous attempts by the Obama administration to include the Pacific into its “Asia-Pacific rebalancing” plans over a decade ago produced few results.

“Since then, China has increased its own diplomatic and economic footprint in the region, with the biggest concern being the Sino-Solomon Islands security agreement,” he added. It was signed in April, with island officials saying the deal would not result in Chinese military bases or a long-term presence.

Lanteigne said the decision by Solomons’ Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare to skip the US-organised August 7 commemorative event marking the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Guadalcanal should be “seen as a warning sign that there remain suspicions in some parts of the region about American efforts to restart its Pacific diplomacy”.

“Questions which Pacific leaders are likely now asking are whether these American initiatives are purely reactive in light of Beijing’s recent diplomatic moves, and whether these recently announced US investment plans will dissipate after this year’s midterm elections or a possible change in administration after 2024,” Lanteigne said.

Starting on August 7, 1942, the Guadalcanal campaign was a six-month series of battles fought between Allied forces and Imperial Japan on and around Guadalcanal, the largest land mass in the Solomon Islands.

Zhu said that while Washington “may have an agenda” of countering China at the White House meeting next month, Pacific Island countries were likely to push the US to do more on climate change.

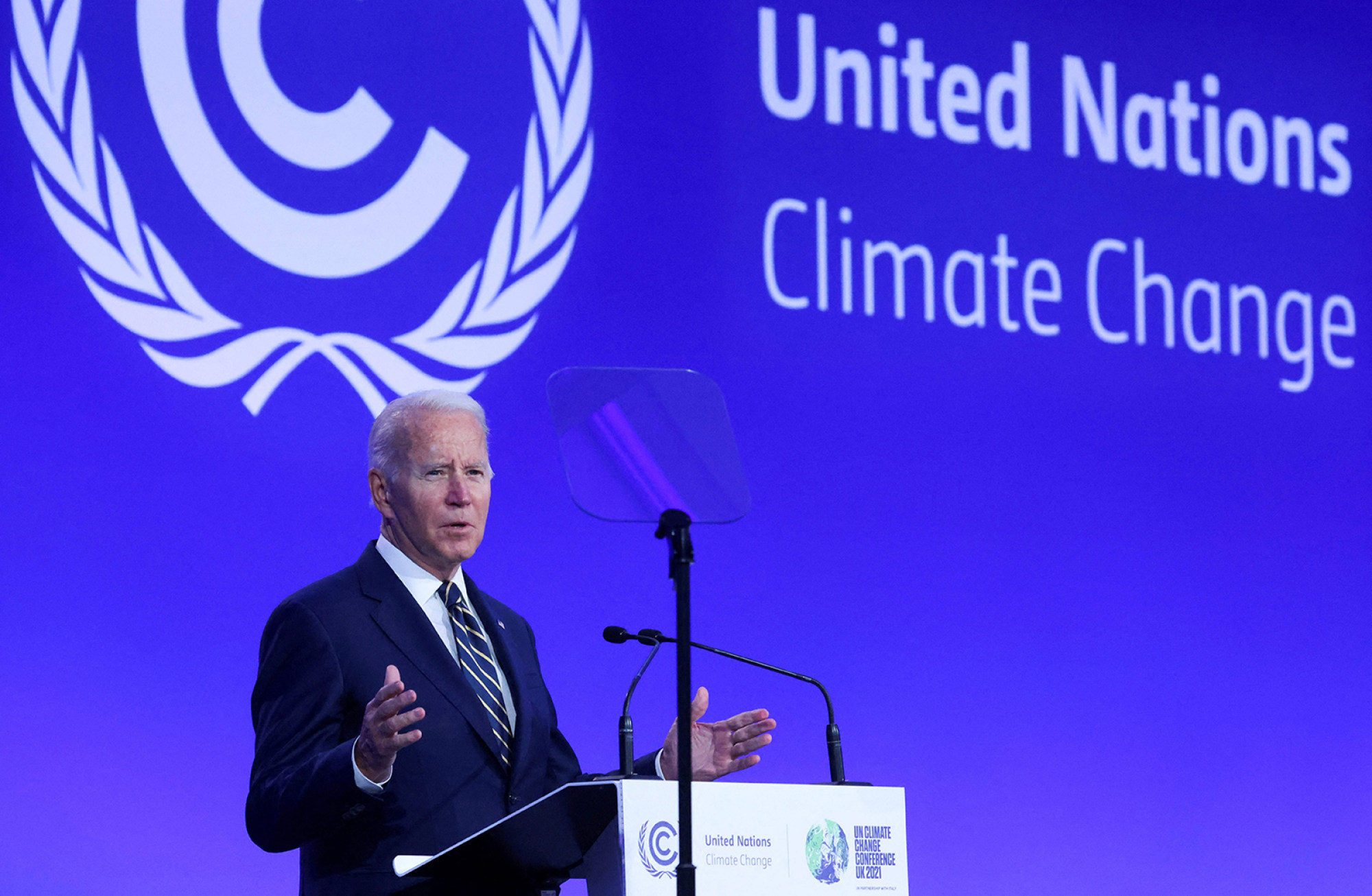

Noting that the US has often been seen as a global leader, Zhu said the perception would be eroded by its inability to provide “solid solutions for global crises, such as climate change, political and economic stability”.

He said the US “is on the track of declining in many different areas” and said its own economy “is not strong, with huge debt and inflation”.

But these are unlikely to be granted in view of increased protectionist tendencies in the US, with policymakers making it clear that the IPEF will focus instead on building connected and resilient economies.

Pacific nations don’t need West’s ‘lectures’ about China ties, Kevin Rudd says

Lanteigne said there were hopes that next month’s meeting between Biden and Pacific leaders would not simply be “a photo-op but rather a strong signal that the US is truly back in the region, and not just focused on the Pacific Islands as an arena for balancing China”.

Shiozawa noted that while the US had been providing help in the field, actual dialogue with Pacific countries had been lacking.

“It will be the first-ever US-Pacific leaders meeting in history,” he said, adding that the meeting was expected to lead to more robust relations between Washington and the islands.