Why Sri Lanka’s ‘Aragalaya’ protesters are divided on backing President Ranil Wickremesinghe

- The debt-ridden country saw more than four months of protests this year over the mismanaged economy and major shortages of necessities

- Analysts said former protesters are divided on what to do next; some are keen to continue protesting, others want to give new leader a chance

Dushantha, 28, who set up the protest group Black Cap Movement in March with 1,000 members said he and his colleagues laid out “a series of demands related to constitutional reforms for the next six months”. “At this stage, we want to deal with the government and not disrupt it,” he added.

However, not everyone is happy to work with the new president. Maths tutor Thisara Anuruddha Bandara, also 28, was arrested twice during the months-long protests and left his job in May to be part of the movement 24/7.

“We, the ‘Galle Face protesters’, are soon going to reorganise the protests, which will be much bigger and more effective than the previous one,” he said.

Both Dushantha and Bandara were part of ‘Aragalaya’ (the struggle) that started in March, calling for the removal of Rajapaksa and his brother Mahinda, the former prime minister, because of a severe financial crisis that led to major shortages of fuel, food, and medicines.

China’s Xi offers Sri Lanka’s new president support amid crisis

But now the Rajapaksa brothers are no longer in charge, the protesters look divided, according to analysts.

Sociologist Kalinga Tudor Silva said that while the protests initially led to a rare “political” and “social” awakening and saw participation irrespective of class, caste, ethnicity, gender, religion and profession, Wickremesinghe had “divided” Aragalya protesters.

Many ordinary citizens have pointed out that the price of many necessities – including petrol, bread and rice – have tripled since early this year, and the cost of electricity is up by as much as 264 per cent for some, and say that the president is offering too little, too late.

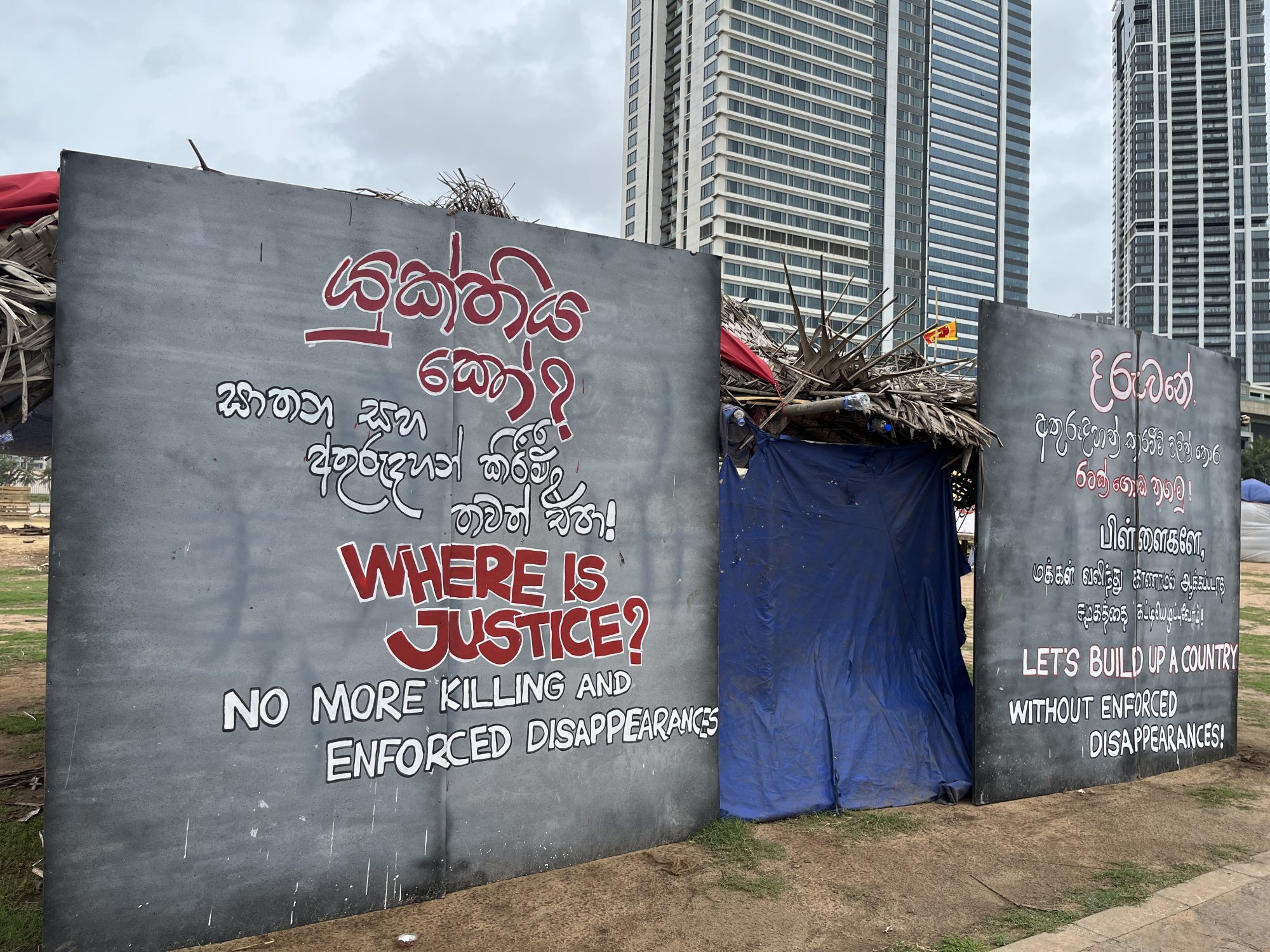

Not as many people are organising or taking part in larger protests as before due to severe police crackdowns, said Bandara.

Police and special forces also forcefully removed protesters sleeping in tents at the main anti-government demonstration site in Colombo and some were beaten and assaulted, said Amnesty International last month.

“The liberal rich believe Wickremesinghe is better than Rajapaksa. A lot of people have left the protests because they have either faith in Wickremesinghe or they are scared to face repression,” Silva said.

Human rights defender Ambika Satkunanathan said that the business and privileged class, who have always been supportive of Wickremesinghe, see “stability” as incompatible with protests and dissent.

Can Sri Lanka’s Ranil Wickremesinghe steer the country out of its crisis?

Sociologist Ahilan Kadirgamar said Wickremesinghe is carrying out a “counter revolution with tremendous repression,” which will eventually make it clear who is on which side.

Sections of the Colombo elite have thrown in their lot with the new prime minister, while the mass of people who are facing food inflation of around 90 per cent are bound to resist the repression and dispossession.

“But this repression may lead to another wave of powerful struggles,” said Kadirgamar, a senior lecturer at the University of Jaffna.

Adding that the “smaller section of people” who have left the movement to support the current government were mostly Wickremesinghe supporters and they had only wanted Gotabaya to resign, Bandara said there were a larger number of protesters who had earlier chanted “Gota, go home” and were now chanting “Go, Ranil, go.”

Wickremesinghe ... is not the people’s president, only another protector of the corrupt system

“These protesters never wanted Wickremesinghe to assume power because he is not the people’s president, only another protector of the corrupt system,” said Bandara.

Wickremesinghe, who once labelled the protesters “fascists”, is “shrewd” but does not have his ear to the ground, said Father Nandana Manatunga, head of the Kandy-based Catholic non-profit Human Rights Office. He said he thought the new leader should be grateful to protesters as he would have not been able to come to power without them.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa appointed Wickremesinghe as prime minister in May after Mahinda resigned. Last month, Rajapaksa’s Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) party, which has a majority in the 225-seat parliament, elected Wickremesinghe as president after Gotabaya fled to Singapore.

SLPP, however, now wants the new president to facilitate Rajapaksa’s safety upon his return to Sri Lanka.

Satkunanathan, a former commissioner at the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, is in favour of an election as soon as the constitution allows it since the public mood is still mostly against those in power.

She said that when protesters occupied public sites, including the president’s official residence, they symbolically reclaimed power and sent a message that they wanted a more “equitable, transparent and accountable” system.

Adding that they have asked the president to revoke emergency laws that give sweeping powers to the police to search and make arrests and the executive presidency, Dushantha said different groups were looking “at the future course of action differently”, wondering “how many people [in power] do we send back home” and “who will rule the country” until there is another election.

But protester Bandara said those who have had discussions with Wickremesinghe are welcome to join the protests again, as and when they understand that the new president cannot provide the changes they want.

Zero-Covid Bhutan bans vehicle imports to stave off a Sri Lanka-style crisis

Wickremesinghe, who has equated politics to a “hard game like rugby” in 2019 and ran unsuccessfully for president twice – in 1999 and 2005 – is a man known for keeping his cards close to his chest, analysts said.

Wickremesinghe was introduced to politics by his uncle, former president Junius Richard Jayewardene, who brought in the executive presidency in 1978 and passed the Prevention of Terrorism Act that led to gross human rights violations such as enforced disappearances and unlawful killings.

He has been elected prime minister six times but never completed a term. During his last term, between 2015 and 2019, his image was marred in a bank bonds scam involving a former schoolmate he hand-picked to be bank governor. In parliamentary elections in 2020, his United National Party did not win a single seat.

But, Silva said, what works in Wickremesinghe’s favour is that he is not seen as a “Sinhalese Buddhist nationalist”, like those in the Rajapaksa family.

“Plus, he doesn’t have children, so he won’t have interest in building up a lineage or accumulating wealth,” Silva added.

Arjuna Parakrama, an English professor at the University of Peradeniya, however, believed Wickremesinghe was using the crisis to push through a neoliberal agenda of privatisation, reduced subsidies and safety nets, and the destruction of free healthcare and education.

These policies have been the cornerstones of Sri Lanka’s development philosophy even during the depths of civil war.

Sri Lanka’s new president is a schemer, not the man to lead it out of crisis

Namal recently asked environment minister Naseer Ahamed to accommodate two people of his choosing in a subsidiary company of national entity the Geological Survey and Mines Bureau. Dushantha’s Black Cap Movement has vehemently opposed any move by the government to accommodate Namal in the new cabinet.

Kadirgamar said it is in the interests of the Rajapaksa family and Wickremesinghe to continue with the current arrangement until 2024 as “all of them are likely to get hammered” in any early election.

But, he added, the Rajapaksa family has been “banished from politics for the foreseeable future” and it would be difficult for Namal to make a comeback into any significant position in the next decade.