Amid Singapore’s reopening boom, city’s vaunted ‘affordable public housing’ leaves citizens feeling priced out

- Home affordability a key gripe among Singaporeans, with some in limbo after government imposed cooling measures to ease red-hot property market

- Measures expect to dampen demand and help keep public housing affordable, cool the private residential market, analysts note

Singapore’s recent policy tweak to taper demand in its sizzling public housing resale market has left some of its citizens feeling troubled.

Some middle-class Singaporeans had sold their private properties at a lucrative profit, with the aim of downsizing to a public housing flat – only to find out they couldn’t.

Singapore rents go through the roof again, up 9.9 per cent

This means the so-called downgraders would have to hunt for an alternative place to put up during that period, either by renting or staying with their relatives.

But property agents said not all who were affected had the intention of profiteering off the red-hot property market.

Clarence Foo, senior associate division director at Propnex Realty, said some elderly were just “getting cash out so they have money for retirement”.

“The older people don’t make money from doing this,” he said.

The new rules do not apply to people aged 55 and above seeking to downgrade to a three-bedroom or smaller resale flat, but Foo suggested others might not be so fortunate.

In one case, a couple in their late 40s were forced to sell their private property after losing their jobs. “It’s very real. The only way they could keep the family going is to sell their condominium,” Foo said.

The so-called downgraders – now temporarily frozen out of the public house market unless they receive waivers – are not the only ones wondering if the system is all that it is made to be.

Home affordability has become a key gripe, even among those meant to benefit from the public housing system.

Close to 80 per cent of Singapore’s population – its growing middle-class included – live in government flats built by the Housing and Development Board (HDB). These are sold to citizens at a considerably affordable price for a 99-year period.

In the city state, these flats have generally been viewed as assets that can either be sold for profit in one’s later years or inherited by the next generation.

Rising property prices

Singapore, which has held a flurry of activities and large-scale events since last month as part of its reopening, has experienced a boom in both its private and public property markets in recent months.

Government data in October showed that prices of resale public houses rose for the 10th consecutive quarter, with properties changing hands at higher sums. In this year alone, more than 260 public flats, mostly in mature and prime estates, have been sold for over S$1 million (US$699,000).

Expatriates ditching Hong Kong stoke Singapore home rents to 2014 high

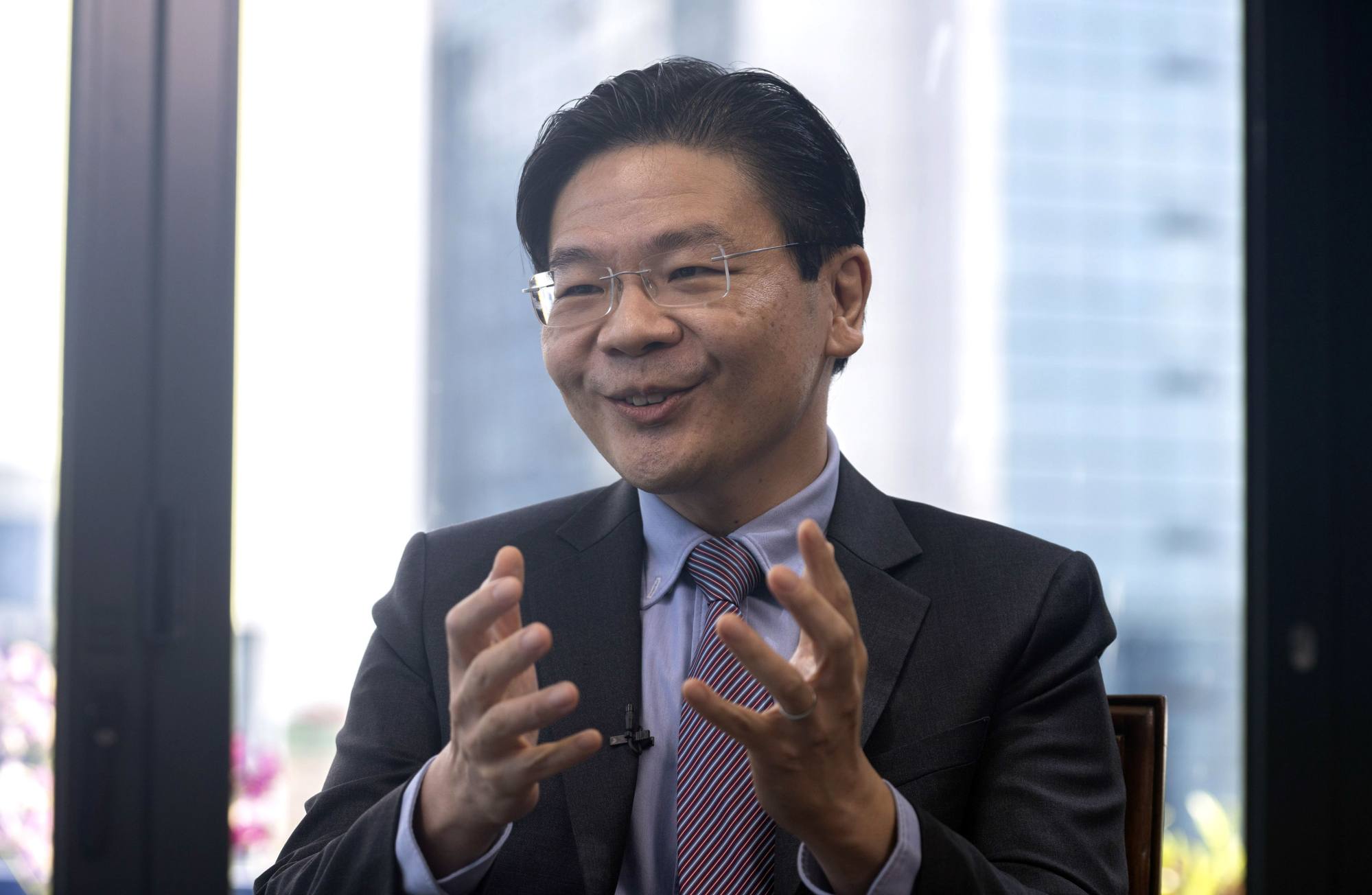

Minister for National Development Desmond Lee said factors behind soaring resale property prices included a wave of younger Singaporeans opting to buy their own homes instead of living with their parents, and more homebuyers turning to the resale market because of longer waiting times for newer flats.

There were also more private property owners who were riding on the red-hot market and cashing out for profits, he said, when explaining the measures in parliament. The number of private property owners buying resale flats had doubled in 2021 and the first three quarters of this year compared to 2019 and 2020.

Lee said the 15-month cooling-off period aimed to “moderate demand and slow the momentum of price increases” of resale flats by deferring demand from private property owners.

“We are committed to keeping public housing affordable and accessible to meet the housing aspirations of Singaporeans and to help Singaporeans own their own homes,” Lee added. “This is a key long-standing national priority and provides the basic foundation for us to raise our families, bring up our children and build strong communities.”

The government also sought to dampen borrowing by homebuyers by concurrently lowering the loan-to-value ratio and raising the medium-term interest rate floor used by banks, in the latest round of measures.

What Lee raised were issues that younger couples in Singapore were grappling with. Amanda Woon, a 26-year-old behavioural change researcher who recently bought a four-bedroom resale flat with her fiancé, pointed out that prices had risen “so rapidly” and were almost 30 per cent higher than two years ago.

Her flat, in the western Bukit Panjang neighbourhood, had cost her S$590,000.

“With the rising resale prices, we felt that many of those who were selling were looking to make big bucks out of the public housing market. I think there was this sense of disgruntled-ness towards the situation,” Woon said. “We realised that even for the neighbourhood we were looking at, where sale transactions were fairly low, the prices were jumping.”

Is Singapore still a ‘tenant’s haven’ as rents rise, Hong Kong expats arrive?

Woon had opted for a resale flat as she felt that competition was stiff for new builds and the waiting times were much longer. Currently, new flat buyers have to wait for about five years compared to three years before the pandemic.

She would also have more oversight over the flats she could buy in the resale market. “Essentially, we wanted to have more control over what we wanted. Things like where the flat is facing, the convenience of the area, the views and the layout,” she said.

With the strong demand for public housing units, the Singapore government has pledged to launch up to 23,000 new flats – more popularly known as Built-To-Order or BTO – this year and in 2023, up from the 17,000 in 2021. Lee, the minister, has said 100,000 flats could be launched from 2021 to 2025 if needed.

Dampening demand

Foo, the Propnex Realty director, expected the new measures – which kicked in on September 29 – to have an immediate impact in bringing down prices of larger resale flats.

The policy change would divert the cash-rich away from public housing and keep public flats affordable and within reach of their target market, such as “genuine downgraders” or young families looking for their first homes, added Catherine He, head of research at Colliers.

She suggested that the measures would also indirectly cool the private residential market. This is because the pool of public property upgraders profiting from higher resale prices would shrink. Mass-market projects, which target this group of upgraders, were most likely to be affected.

“There will probably be a knee-jerk reaction from buyers and developers as they adopt a wait-and-see stance for one or two quarters to evaluate how the measures would affect them,” He added.

Singapore’s housing shortage threatens to fuel rising prices

Nicholas Mak, head of research at the Singapore-based APAC Realty unit ERA, said it was expected that Singaporeans affected by the fresh round of cooling measures would feel short-changed, given that some had been unable to purchase a public property for more than a year.

But he defended the government’s decision, saying these so-called downgraders were typically more well-off in asset terms compared to others. “They already have a roof above their heads and the government’s objective is that everyone will have a roof above their head,” he said.

More significantly, the government has stressed that the measures were intended to be temporary and would be closely monitored and reviewed – the first time authorities have said that of their property cooling measures. Mak said there was a “good chance” the measures would be rolled back once resale property prices stabilised.

The government, he went on, likely implemented the measures to dissuade people from over borrowing instead of just artificially bringing down prices of resale property.

“In the public housing resale market, you have a buyer and seller sitting on opposite sides of the table. If the government brings down prices, the buyer is happy but the seller is unhappy,” he said. “When the general election comes, both of them will vote.”

A hot-button issue

Political analyst Felix Tan suggested there would be some level of concern among younger Singaporeans who have seen property prices soar, especially in the resale market. This is so as public housing flats were “supposed to be affordable”.

“If the government does not mitigate the situation and plug the loopholes in its system, many more younger Singaporeans will not be able to afford their own homes in the near future, especially for those who are intending to marry and settle down in their own abode,” he said. He suggested the republic’s housing woes could mirror Hong Kong’s if steps were not taken to ease the situation.

The average waiting time for renting a public flat in Hong Kong is six years. About 15.7 per cent of the city’s 7.3 million people own public flats, with 30 per cent living in public rental flats. Hong Kong’s comparatively low stock of public housing is seen as a key factor behind its seemingly intractable housing crunch.

Singapore’s homebuyers in bind as public housing prices close to record levels

Tan, an associate lecturer at Nanyang Technological University, said property prices had always been a core issue in Singapore’s general elections.

“This time around, the problem might be quite different since the crux of the affordability issue seems to be in the resale market,” he said.

Analysts said it was too early to say how long it will take for the cooling measures to achieve the key aim of dampening demand. The government may have to contend with a fresh headache if the measures cause more people to rent, leading to higher leasing prices.

Restrictions on private homeowners downgrading to public housing flats could also mean they may instead choose to move to cheaper private condominiums outside the city state’s central region, driving the prices of these units higher.

Although a general election has to be called only by 2025, observers have suggested that the country could head to the polls as early as late 2023.

While Tan said rising property prices could be an issue during election hustings, he did not feel the recent measures had to do with an impending election.

“I do believe that, with the recent changes, the Singapore government has made some policy changes to mitigate the problem and bring down the property prices,” Tan said. “This will help to a certain extent to curb the rising costs of public housing.”