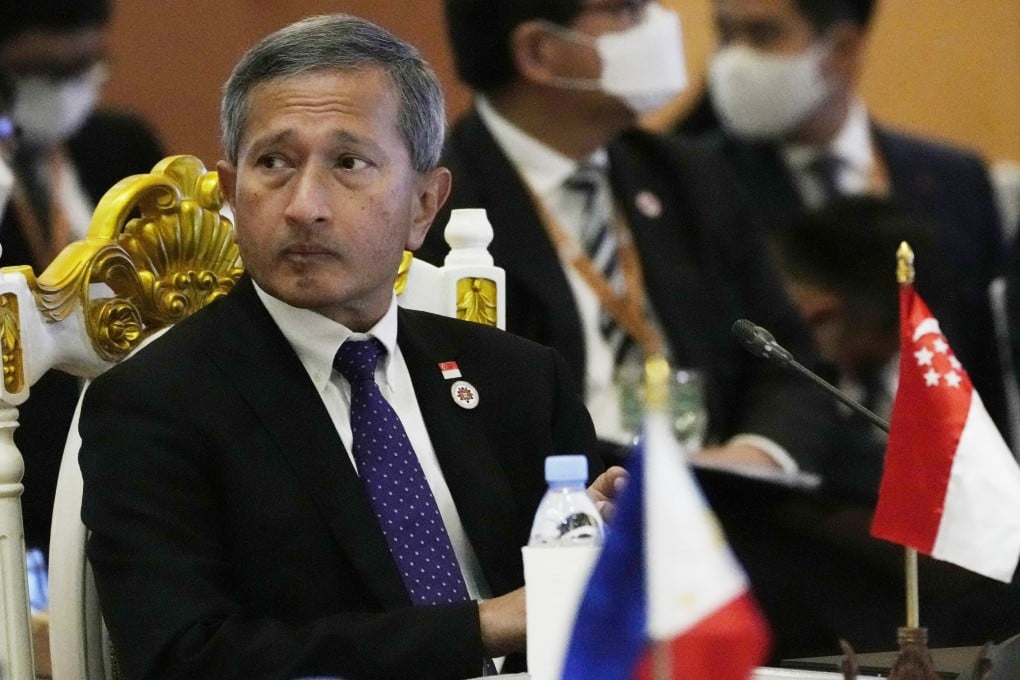

Asean has no licence to interfere in Myanmar’s internal affairs: Singapore

- Myanmar’s troubles with national unity has been going on since WWII and the coup only exacerbated that, Singapore’s foreign minister Vivian Balakrishnan says

- While Asean member states condemn the military coup, it does not give them the right to interfere in Myanmar’s internal affairs, he adds

Answering questions about Myanmar during a debate on the foreign ministry’s budget, Vivian Balakrishnan underscored that the country had been struggling to forge a common identity and bring its various component parts together since World War II.

“This coup, two years in the making, has not helped,” Foreign Minister Balakrishnan said. “If you ask me for my opinion, I think it is a dead end. It’s not going to be to a road where you will achieve national reconciliation.”

“So we must understand that although we clearly disapprove of the coup, and we don’t recognise the current military junta, it does not give Asean a licence to interfere in its domestic affairs,” he said.

Balakrishnan suggested that the attendees of the meeting – the “immediate neighbours” of Myanmar – faced a “risk of refugee outflows” and “would be at a greater hurry to see a resolution and may be prepared to compromise on the means by which the post-coup crisis is resolved”.