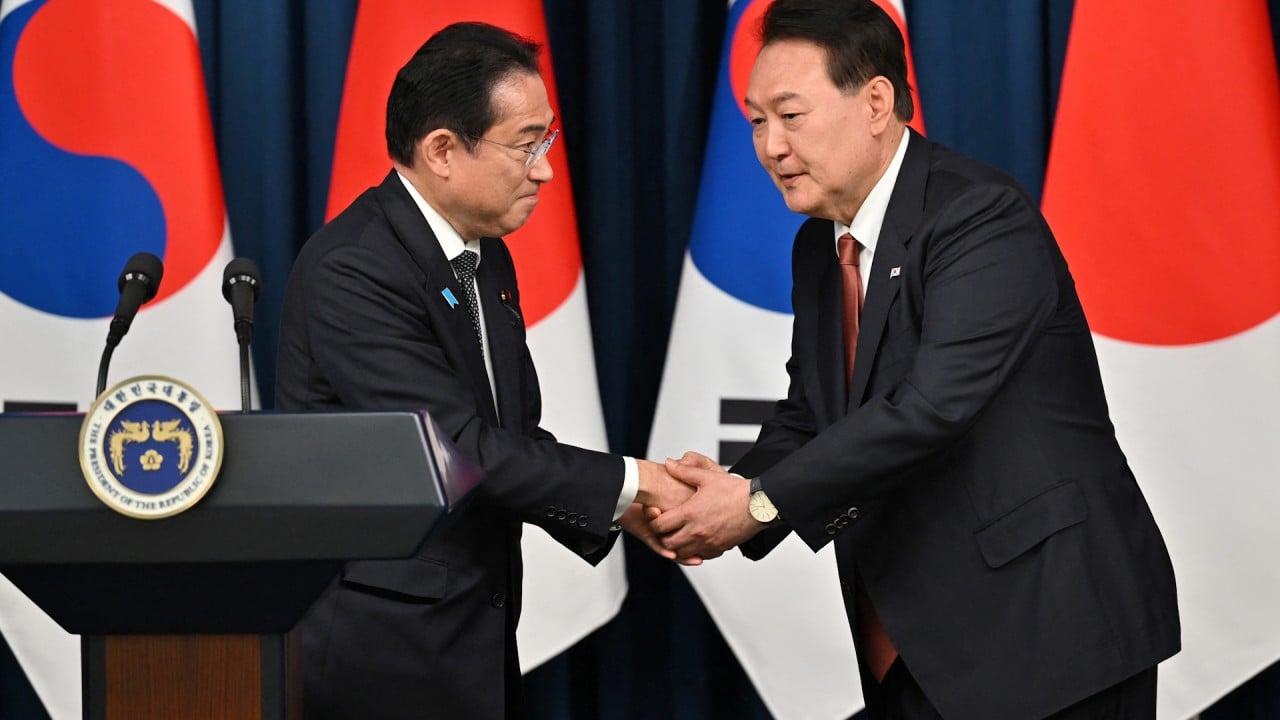

‘Calibrated response’: can Yoon stabilise Korean peninsula even as he boosts ties with US, Japan?

- Yoon, who marks his first year in office this week, is charting a new course in South Korea’s foreign policy and security, analysts say

- He overturned his predecessor’s policy of reconciliation with North Korea and abandoned balancing US, China in favour of stronger ties with US, Japan

“If I think back to this time last year when I took office, there is no area that has seen greater change than foreign policy and security,” Yoon said at a government cabinet meeting on Tuesday.

He said that under his government, South Korea also resumed field military drills with the US that were either reduced or suspended under Moon’s government to pursue dialogue with Pyongyang despite angry North Korean reaction.

He pushed through with the settlement of the compensation issue involving Korean victims of Japan’s wartime forced labour, by proposing that they be compensated through a Seoul-based fund instead of seeking reparations from Japan.

“I can’t accept the notion that because of what happened 100 years ago, something is absolutely impossible [to do] and that they must kneel [for forgiveness] because of our history,” he said in an interview with The Washington Post, sparking outrage among opposition and critics.

Yoon’s alleged predilection for a friend-or-foe dichotomy, developed during his decades as a state prosecutor, appears to be spilling to diplomacy.

“President Yoon pursues consistent, clear-cut diplomatic paths in favour of a bolstered alliance with the United States and stern, proportionately calibrated responses to the North’s provocative acts,” said Bong Young-shik, a lecturer at the Yonsei University’s Institute for North Korean Studies.

Military alliance with US, Japan ‘unnecessary’: South Korea opposition chief

Similar to the stock market where uncertainties are worse than bad news, Bong said Yoon’s diplomacy had a positive side as long as it sent clear messages to the North, China and Russia as to “what they can do and what they cannot do in relation with the South”.

This diplomatic signal “lowers the risks of causing miscalculations or misunderstandings”, he said.

“The flip side is, however, there are increasing risks of North Korea seeking to maximise South Koreans’ growing concerns over armed conflicts by resorting to military provocative acts” to discredit Yoon’s hardline posture, Bong told This Week in Asia.

Cho Jung-kwan, a political-science professor at Chonnam National University, said there was no other alternative for Seoul but to close ranks with Washington and Tokyo amid the mounting US-China rivalry.

“However, Yoon appears to be pushing through with an early settlement of the forced labour issue with Japan to pave the way for a rapid US-led three-way defence cooperation under Washington’s pressure at the cost of Koreans’ national pride,” he said.

Aside from the North’s nuclear threats, China represents one of the most serious diplomatic challenges for Yoon amid concerns that China may hit South Korea with reprisals for taking sides with the US in the intensifying superpowers’ rivalry for hegemony, and making remarks dabbling in the issue of Taiwan that Beijing sees as a renegade province.

“However, China would not repeat the folly of adding to anti-China resentments in this country that emerged after Beijing hit South Korea with economic reprisals” over Seoul’s 2016 decision to deploy the US anti-missile defence system known as THAAD, Cho said.

South Korea begins THAAD missile system upgrade despite local protests

Critics say Yoon, while focusing on the bolstering of alliance with the US, is failing in reducing risks and returning stability to the Korean peninsula.

“There is no dialogue but confrontation … a new Cold War is brewing between the South, the United States and Japan on one side and the North, China and Russia on the other,” said Yang Moo-jin, a political-science professor at the University of North Korean Studies.

“Tensions are higher than before and the North’s nuclear weapons are more numerous and powerful than ever. In that sense, the Yoon government has achieved none of its North Korea policy goals – denuclearisation, peace and co-prosperity,” he said.

Domestically, Yoon’s supporters credit him for getting tough with strikes from labour unions.

But Yoon, who leads the conservative People Power Party, faces criticism for his failure to engage in talks with the opposition Democratic Party of Korea amid a slowing economy, growing social inequality and housing woes.

Consequently, Yoon made no tangible progress in efforts for legal reforms in the face of strong objections from the opposition party, said Choi Jin, head of the think tank Institute for Presidential Leadership.

“Efforts for improving people’s livelihood were drowned in the political vortex sparked by a deepening gulf between the two rival parties” as Yoon sought to introduce more market-oriented reforms, Choi said.