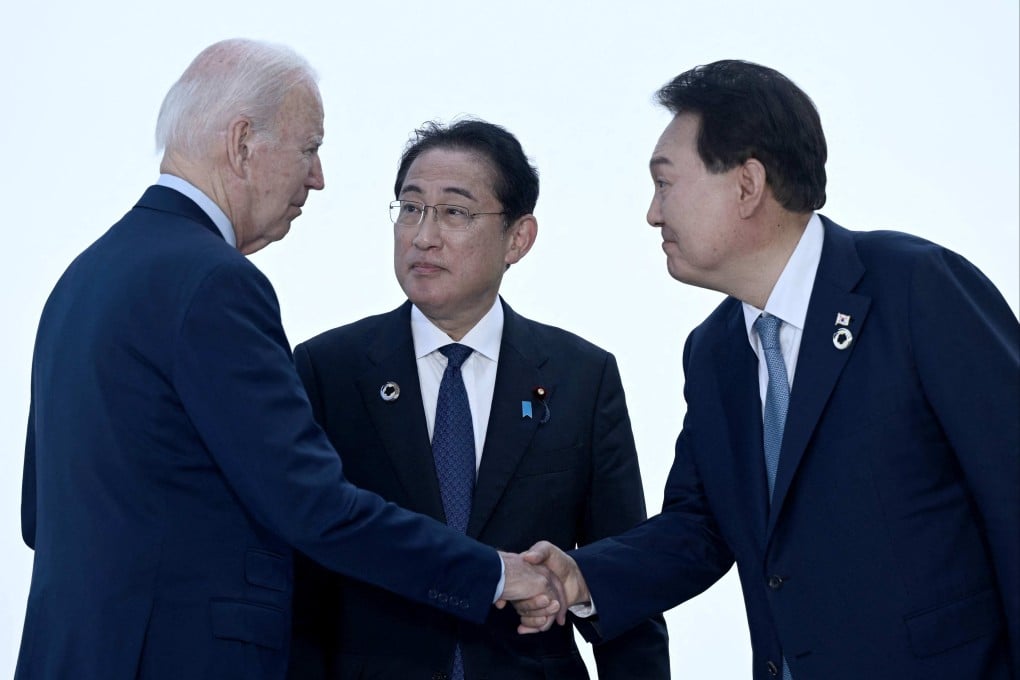

Can Japan, South Korea seal ‘historic’ security alliance at US summit amid China, North Korea threat?

- A formal security alliance between Japan and South Korea may be difficult to conclude, but a pact involving the US ‘would be much easier to achieve’, analysts say

- While Japan welcomes improved ties with South Korea, questions remain about the sustainability of agreements given previous track record

A trilateral arrangement involving the US is likely to be easier to achieve, although experts say such a pact would still face numerous obstacles, not least opposition from other regional powers that have already expressed concern about the evolution of an “Asian Nato” security grouping.

The aim is for Kishida and Yoon to agree that they need to work more closely together to improve their joint deterrent capability and commence defence coordination and cooperation.

“Basically, an agreement on security like this could be a plus for all three parties, but I fear that if they try to go for a full treaty, it will involve too much politics, too much bureaucracy, and use up too much political capital,” said Ryo Hinata-Yamaguchi, an assistant professor of international relations at the University of Tokyo.

“But if they are just talking about greater cooperation and coordination, then that is doable and would build on what we have already seen since the Yoon administration came to power,” he told This Week in Asia.