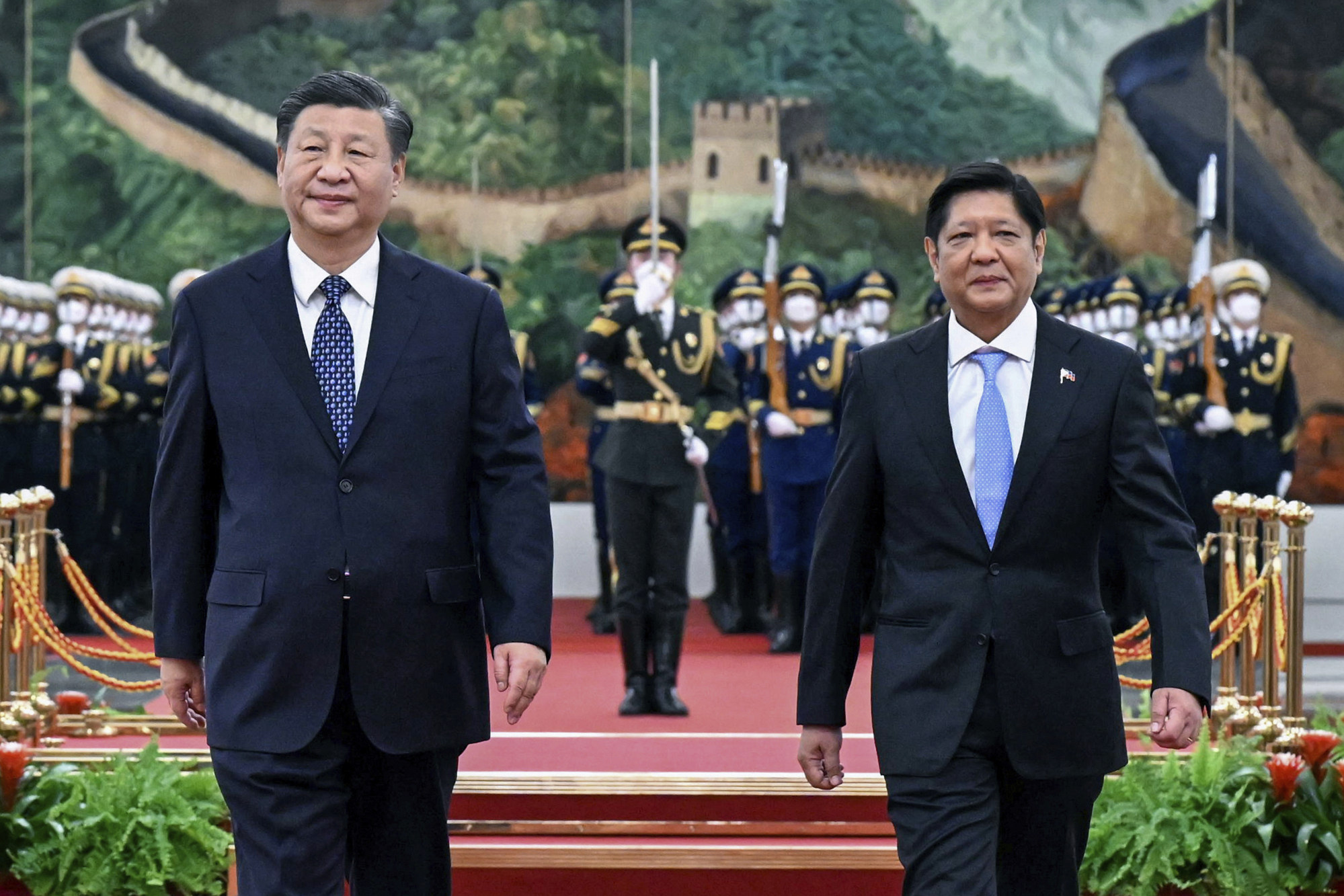

Philippines-China relations: as Manila cancels billions in Chinese rail funding, are South China Sea tensions to blame?

- In scrapping US$5 billion worth of rail projects, the Philippines cited Chinese foot-dragging over financing rather than their squabbles at sea

- But observers speculate it was Manila’s refusal to back down in the disputed waterway that had caused Beijing to hold back on the cash

Wider geopolitics appear to be steering the strategy, as the Philippines puts principle over its aching need for an infrastructure upgrade.

China appeared to be no longer interested. So we’ll look for other partners

“China money is important,” said Chester Cabalza, president and founder of the Manila-based International Development and Security Cooperation (IDSC) think tank. “[But] protecting one’s sovereignty and territorial integrity is more credible” than “Chinese political and economic coercion”, he said.

In scrapping US$5 billion worth of rail projects, the Philippine government said it was reacting to foot-dragging by China over financing rather than the squabbles at sea.

But observers speculate that it was Manila’s refusal to back down in contested waters that resulted in China holding back on its cash pledges.

Scarborough Shoal grey zone tactics add to China-Philippines tensions

“China appeared to be no longer interested,” Transportation Secretary Jaime Bautista said on October 27, referring to the other rail projects located outside the Philippine capital. “So we’ll look for other partners.”

A formal notification is in the works to “terminate” the funding for the 50-billion peso (US$891 million) Subic-Clark freight railway, which would link two former US military bases turned commercial zones, and a proposed long-haul commuter railway in the southern part of the main Luzon Island valued at 175.3 billion pesos (US$3.1 billion), Bautista added.

China’s economic muscle

The situation at sea has dangerously deteriorated in recent weeks.

The Scarborough Shoal is at the heart of the dispute. It is the strategic centre of the South China Sea, a major arterial route for shipping crucial to China’s multitrillion-dollar maritime trade.

Over the past decade, China has intensified its claim to “historic rights” in the disputed waters, deploying naval and fishing vessels to block Filipino fishermen from accessing the shoal.

As recriminations backlight relations, Tan See Seng, research adviser at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, said it was hard to imagine that Manila’s decision on the railways had nothing to do with the rancour over the shoal.

“Let’s not forget the Philippines have been at the receiving end of Chinese economic arm-twisting before,” Tan said, noting that after a 2012 Scarborough Shoal incident, China restricted banana imports from the Philippines. “We cannot rule out the possibility of continued Chinese pressure on the Philippines.”

During the April 2012 incident, the Philippine Navy tried to apprehend eight Chinese fishing vessels near the shoal, which is claimed by both Manila and Beijing.

The move resulted in cyberattacks and hacks attributed to China, the suspension of Chinese tour groups to the Philippines and stricter Chinese regulations on imports of Philippine bananas, described by some media reports as a “banana crisis”.

“The maritime spat has come to affect economics” said Lucio Blanco Pitlo III, a research fellow at the Manila-based Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation think tank, warning infrastructure cooperation may be just the first casualty, with trade and investment next.

As recently as January, things looked very different.

“Manila’s snub may have influenced Beijing’s interest in funding its neighbour’s projects,” Pitlo said, adding that China had “rewarded” regional countries that had “consistently attended” belt and road forums.

The Philippines has big ambitions for new rail lines to connect a country whose infrastructure has decayed amid years of underinvestment.

Failure to follow through on economic pledges helped drive the [Philippines’] … pivot away from China and back towards the US

“But the core problem is that almost none of the more than US$30 billion in Chinese loans and investment pledges made during the Duterte administration have been delivered,” said Gregory Poling, a senior fellow and director of the Southeast Asia programme at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

“That failure to follow through on economic pledges helped drive the Duterte administration to pivot away from China and back towards the US in his last two years in office,” he said.

The Philippines has gone from a “favourite to … a forgotten hub for Chinese investments”, Cabalza of the IDSC said, adding that there were useful lessons in economic resilience to be learned from tangling with China.

China-Philippines tensions roil, but it’s ‘business as usual’ for trade

Yet geopolitics does not have to mean economic ties are put on ice, said Benjamin Barton, an associate professor of politics, history and international relations at the University of Nottingham’s Malaysia campus – explaining that Manila is confronted with the competing priorities of Chinese business and diplomacy.

“On infrastructure, they will be dealing with policy banks and construction-industry actors, who don’t carry a geopolitical agenda even if they have direct ties to the Communist Party,” Barton said. “Whereas issues in the South China Sea involve military actors, who have a clear geopolitical agenda.”

The weakness in the now-lapsed rail deals may in fact have derived from the initial motivations behind their construction.

Chinese capital and control of billions of dollars of spending on infrastructure has also worried some Filipinos, who are concerned by what they say is a lack of transparency, and poor environmental and labour standards, including the preference for Chinese workers over locals.

Han Hua, co-founder and secretary general of the Beijing Club for International Dialogue think tank in the Chinese capital, pushed back against the idea of diplomatic disputes clouding the economic ties China has with its Southeast Asian neighbours.

“It is in the Southeast Asian countries where the [belt and road] projects enjoyed a robust growth and expansion, be it high-speed railways, industrial estates, or digital economy,” Han said, adding that once political tensions eased, economic cooperation would return.

“My advice to Filipinos would be: do not feel or fear, but move proactively … towards talks with China … to secure the loan arrangement which will benefit the country and the people most.”

If not China, then who?

Japan has emerged as a potential rescuer of the Philippines’ railway plans.

In February, Tokyo agreed to two loans worth up to US$2.8 billion in support of Manila’s North-South Commuter Railway (NSCR) project.

Also known as the Clark-Calamba Railway, the NSCR is a 147km urban rail transit system under construction on the island of Luzon, running from New Clark City in Capas to Calamba, Laguna, with 36 stations.

The railway is designed to improve connectivity and alleviate congestion within the Greater Manila area.

Japan also announced that a coastal surveillance radar would be given to the Philippines through a grant, making Manila the first beneficiary of a newly launched Japanese security assistance programme for allied militaries in the region.

Tokyo is “in need of partners with similar values that will uphold the Free and Open Indo-Pacific”, said Mark S. Cogan, associate professor of peace and conflict studies at Osaka’s Kansai Gaidai University.

The concept underwrites Tokyo’s belief that free trade, the rule of law and freedom of navigation must be upheld as nerves mount over China’s assertiveness in the region.

G7’s belt and road alternative could force China to ‘match global standards’

“This is an opportunity for them to step up,” Pitlo said, referring to the European strategy aimed at working with partner countries in tackling global challenges and investing in infrastructure development.

There is also untapped potential at home in the form of the Philippines’ deep-pocketed business elites, who have started diversifying their portfolios into public roads and railways under the country’s Public-Private Partnership scheme, said IDSC’s Cabalza.

Under the initiative, the government procures and implements public infrastructure and services using the resources and expertise of the private sector, who are in turn assured of a reasonable rate of return on their investments.