Indonesia pushing bill to restrict investigative journalism and increase censorship ‘by any means necessary’: critics

- Activists argue the bill is being fast-tracked to protect the interests of the political elite

- Proposed legislation would also expand regulatory powers over social media and live-streaming platforms

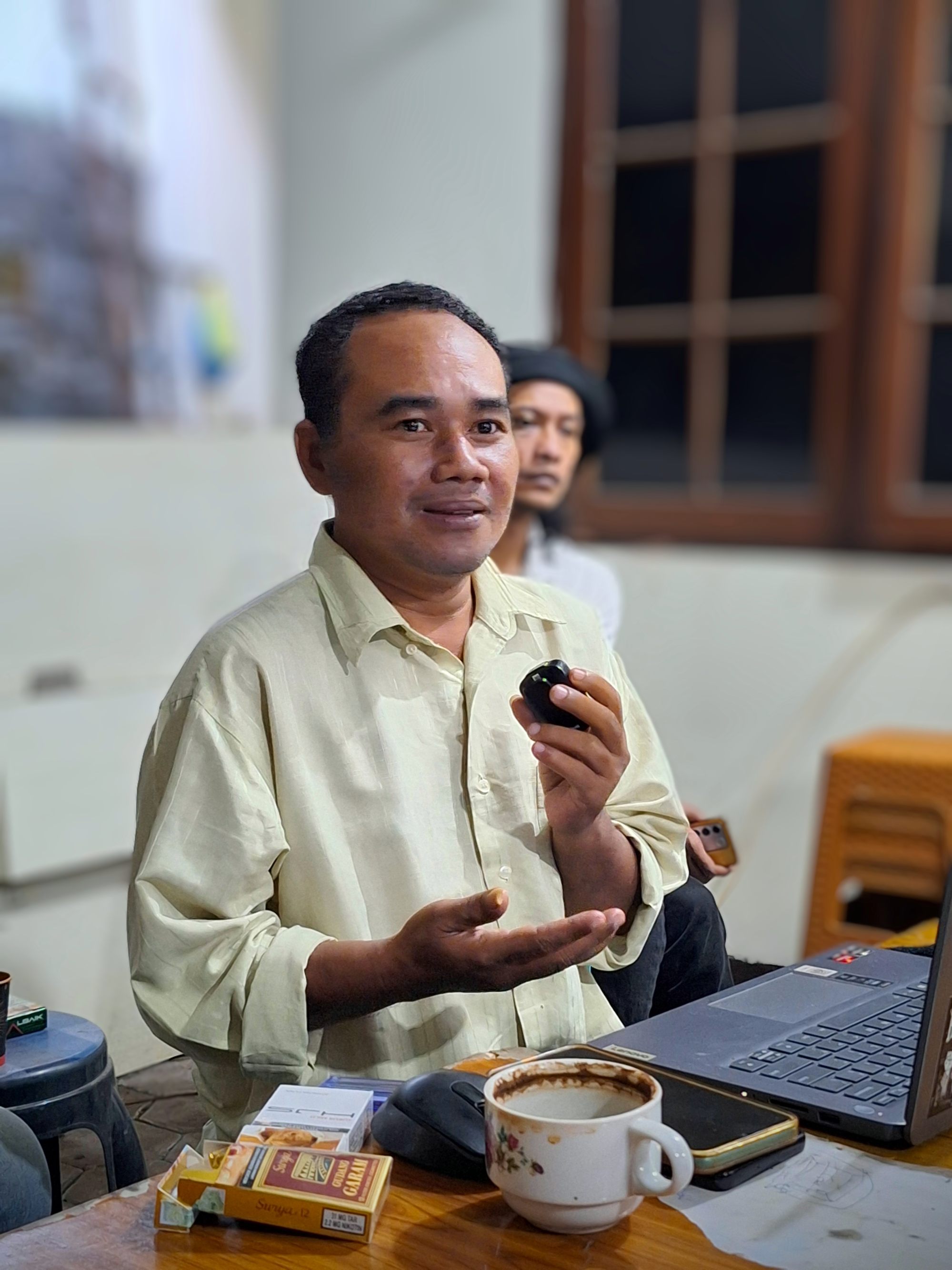

Fatkul Khoir, a lawyer and coordinator at human rights NGO Kontras Surabaya, argued the government was aiming to ensure passage of the Broadcasting Bill before Widodo’s term ends “by any means necessary”.

One of the most contentious clauses seen in a leaked draft of the Broadcast Bill, which is currently tabled for debate in the House of Representatives (DPR), says that electronic and television broadcasts of “exclusive investigative journalism” would be restricted.

“Ultimately, I think, the new law is about safeguarding the interests of the (political) elite. Are there more skeletons in the closet they don’t want us to see?” said Faktul.

Eben Haezer Panca, chairman of the Surabaya chapter of the Independent Journalists’ Alliance, told This Week in Asia, “Trying to restrict investigative journalism strikes at the heart and soul of journalism.”

“Investigative journalists ensured many public scandals in the past, such as the Sambo murder case, were prosecuted transparently through the pressure their work brought on law enforcers.”

Bayu Wardhana, secretary general of AJI, claimed the new law, if passed, would represent “a fresh assault on the spirit of Reformasi”.

“We at AJI unreservedly reject the new the Draft Broadcasting Bill, which we deem to be a regression of democracy,” he said.

Abdul Kharis Al Masyhari, deputy chairman of Commission I of the DPR, defended the bill by claiming its new clauses were “necessary in light of new burgeoning types of mass communication media such as social media and other live-streaming platforms.”

“The old bill only regulated content from terrestrial TV broadcasts, leaving social media and newer platforms virtually without restrictions in airing content that may be unsuitable for children, for instance,” said Abdul, who is a member of the Islam-based Prosperous Justice Party.

Another of the bill’s contentious clauses would take adjudicating authority in journalistic disputes over broadcast news away from the Press Board and reassign it to the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI).

Yovantra Arief, executive director of Remotivi, a media watchdog, said expanding the powers of a government-funded agency, whose job is already to monitor the broadcasting industry for suitable content, would be a step in the wrong direction.

“This could potentially turn KPI into a super body with censorship powers,” he said, adding KPI’s new prerogatives would overlap with those of the Press Board.

Indonesian law currently states the Press Board – an independent organisation made up of journalists and other representatives of the media industry – is the adjudicating body for disputes over the veracity or neutrality of journalistic work.

But DPR member from Commission I Sukamta denied the new bill would create an overlap of authority.

“KPI will only oversee broadcasting disputes, not ones in the print media or online media, so these are distinct fields,” he said in a statement on the DPR’s official YouTube Channel.

AJI Surabaya’s Eben, however, asked where the government would draw the line.

“Most print media also have their streaming and social media content, which the new law also covers. The ambiguity would only create grey areas that could be used to target journalists.”

Made Supriatma, a fellow focusing on Indonesian politics at Singapore’s ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute, questioned the propriety of outgoing President Joko Widodo’s government to try to push through controversial legislation like the broadcasting bill during its “lame duck period”.

“A new DPR has already been elected, as has the new president. So it’s a breach of democratic conventions that the current administration is still trying to legislate new laws, contentious ones at that.”

He reasoned the outgoing parliament could not be held accountable for any new legislation it passed during the transitional period.

“This represents an utter disregard of the voters who already elected a new parliament.”

But Minister of Communication and Informatics Budi Arie Setiadi pointed out the bill was “the initiative of the House of Representatives, rather than the government’s”.

Under Indonesia’s constitution, legislation can be initiated by either the sitting government or the House of Representatives, but passage requires the consent of both before it receives presidential assent.

Minister Budi told This Week In Asia he could not comment on the new bill because the government had not officially received its draft.

“We will of course assess and scrutinise it as soon as we have been given the draft by parliament.”

But he claimed Widodo’s administration was “fully committed to the principle of freedom of expression”.

“In both my official ministerial and personal capacity, I’d like to reiterate that the newly revised UU Penyiaran should never seek to silence the press or repress free speech.”

Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network (SAFENet) Indonesia, a digital rights watchdog, argued in a press release the proposed bill might give rise to arbitrary censorship and repression of free speech, especially in the digital realm.

Lawyer Salawati Taher, coordinator at Legal Aid Foundation Lentera, said the inclusion of a ban on LGBTQ content in the new bill was “pernicious” and “provocative” in intent.

“I wonder if this was a deliberate act by our political elite in parliament.”

She explained that inserting an anti-LGBTQ subsection might be an attempt by the bill’s drafters to generate support for the new law from conservative Indonesians.

“It goes to show how potentially divisive this is, pitting one section of society against another.”

Eben said the discriminatory nature of the bill only proved “anyone could be targeted” if it were passed.

“The public is the ultimate victims here, not just journalists, artists or social media content creators who all use the digital space these days.”

Indonesia’s new Broadcasting Bill may be voted on by the House of Representatives as early as August.