India election: political rivals’ barbs over ties to tycoons spotlight growing income inequality, rich-poor divide

- PM Narendra Modi has alleged Rahul Gandhi made a ‘secret deal’ with the tycoons, while Gandhi has called out Modi for refusing to join him in a debate

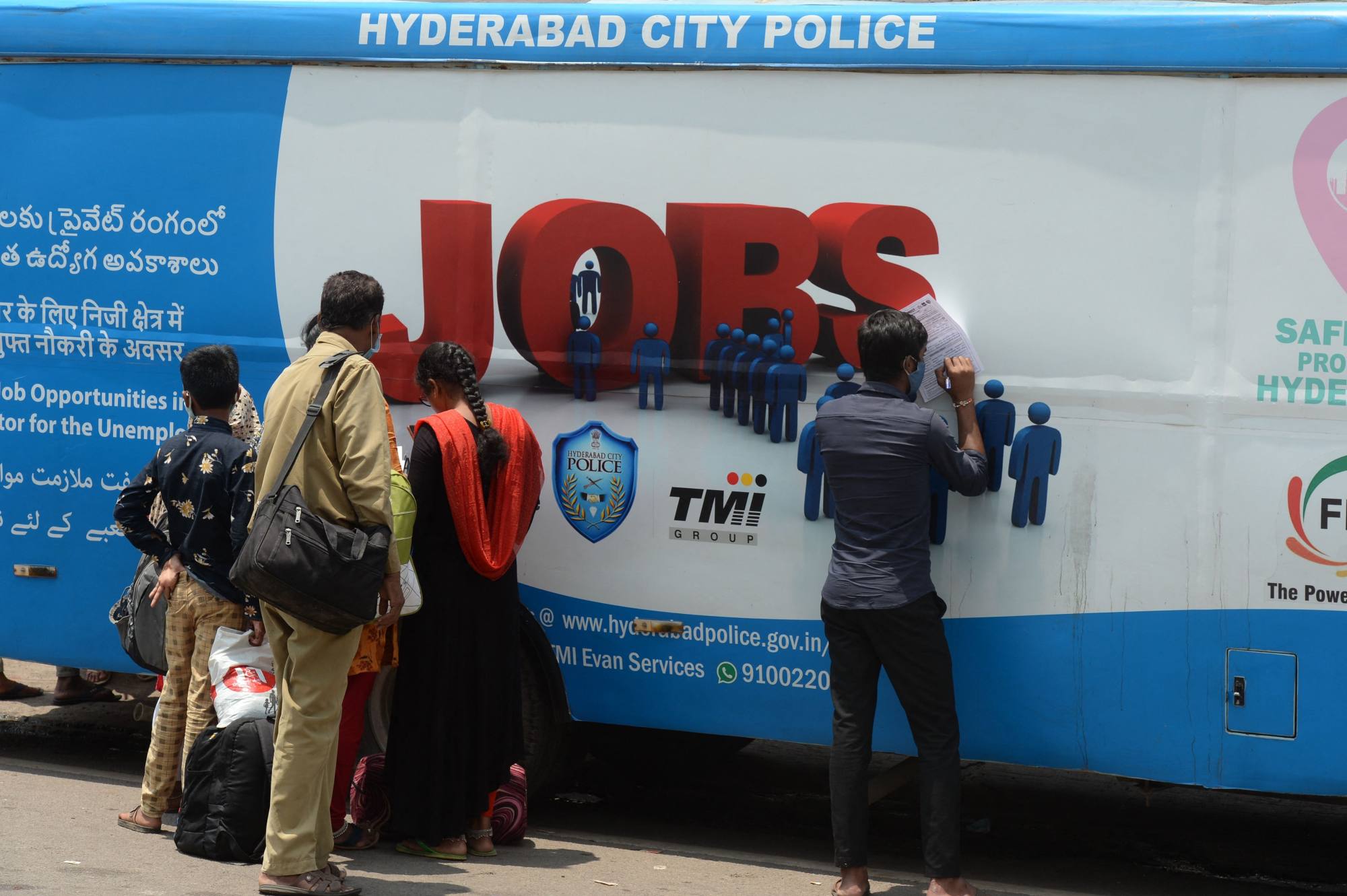

- Income equality has become a key issue for Indians weary of rising costs of living and stagnant wages, with most workers earning below income potential, analysts say

Observers say the trading of barbs between political rivals has spilled over from ties to big businesses to income inequality and the country’s rich-poor divide – issues that will weigh heavily on the ballot.

“Overnight, you have stopped abusing Adani and Ambani. There is definitely something fishy,” Modi told a rally in the southern Indian state of Telangana earlier this month. “The shehzada [prince] should declare how much money he has taken from Ambani-Adani.”

Have “tempo [cargo vehicles] with loads of notes [money] reached the Congress?” he asked.

The prime minister’s charge brought a sharp riposte from Gandhi in an election rally about Modi refusing to join him in a debate.

“If he comes, the first question that I will ask him is Narendra Modi, please tell me what is your relationship with Adani. You have given them ports, airports, other infrastructure and the defence industry,” he said. “He will get trapped there and then.”

The topic of the industrialists’ wealth and the tremendous power they wield in the country has been brought up time and again, and in the previous election in 2019 Congress launched a campaign with the slogan Chowkidar Chor Hai (The Gatekeeper is the Thief).

The campaign bombed after gaining initial support from voters, which is probably why Congress has dwelled more on the theme of income inequality this election, according to Uday Chandra, an assistant professor of government at Georgetown University.

Chandra said Congress had made a subtle shift to focus on welfare programmes this time round rather than harp on the industrialists’ wealth. “Income inequality may not directly impact [people], but it will do so in terms of grievances and demands of disparate groups,” he said.

Rich-poor divide

If voted to power, Gandhi has said he will conduct a socio-economic survey to tailor policies to bridge the gap between the rich and poor, highlighting a March report titled “Income and Wealth Inequality in India, 1922-2023: The Rise of the Billionaire Raj” by global economists which says the share of national income of India’s top 1 per cent is at its highest level historically.

The subject of income equality in India has waxed and waned since the country’s independence in 1947, says Harsh Ramaswamy, an independent political commentator.

A survey by research institute Lokniti-CSDS released in April indicated respondents were satisfied with the BJP’s 10-year rule, but 62 per cent perceived getting a job as increasingly challenging. The survey showed income inequality mattered to most Indians and it remained to be seen how much it would become an issue in the ongoing election, Ramaswamy said.

“The discussion would have some value because the middle class would be interested,” he said.

Voter turnout during four of the five polling phases so far has dipped, indicating a weariness among the public about the ability of political parties to deliver on social justice despite election promises, analysts say.

Two more voting phases will take place before polls close on June 1.

“Income inequality is not only a reality, it has [also] increased over the past few decades. It is true that the Indian economy has been growing at a fairly rapid rate, but the benefits have not been equally distributed,” said Biswajit Dhar, professor at the New Delhi-based research institute Council for Social Development.

Dhar noted that India was suffering from underemployment, with most workers earning below their income potential.

“We are almost in a situation where there is jobless growth. The economy is not absorbing labour and rather the businesses are trying to keep bottom lines intact by downsizing or cutting wage costs,” he said, adding that employees who were laid off fell back on agriculture or took on odd jobs.

“Wage earners are getting squeezed out and profit earners are fattening their pockets,” Dhar said. “Businesses are getting the jobs of two persons done by one.”

The problem has worsened over the past few years because most workers are employed in agriculture, which has suffered because of climate change and erratic weather, he added.

The BJP says, however, that growth in start-up firms has significantly expanded.

In an interview with the India Today group earlier this month, Modi rebuffed the charge of income inequality.

“Earlier there were only a few hundred start-ups in the country, and we have 125,000,” he said, adding that nurturing more wealth creators would usher in higher incomes gradually. “There is a certain process.”

The prime minister also dismissed Congress’ charge about favouring big businessmen.

“Wealth creators should be respected in this nation. If achievers are not honoured, how will the country produce PhD degree holders and more scientists?” he said in the same interview.

Analysts say none of the political parties, including Congress and the BJP, are likely to target big businesses despite talk about wealth redistribution, given their heavy dependency on industrialists for funding their election campaigns.

“The question is of political will. Which government will go and target Ambani and Adani if they are the source of political funding?” he said.

Dhar noted that inequality in India was becoming more complex and “layered”.

“The unemployment rate for people in the age group of 15 to 29 years is 17 per cent. The other aspect is that nearly one in four women are not getting a job when they are looking for one,” said Dhar, citing data from a Periodic Labour Force Survey for January to March.

Without addressing the issue squarely, India would not be able to reap its so-called demographic dividend of having the world’s largest youth population, he added.

Voters told This Week in Asia they would prefer to support a party creating a quality education infrastructure that opened up job opportunities.

Jaiprakash Kanojia, a voter in South Delhi’s Kalkaji, has not been impressed by either Congress or the BJP. Instead, he prefers to support the Aam Aadmi Party led by Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, who was imprisoned on charges of money laundering and recently freed on bail.

“We want someone who works rather than talks. I just met a boy who has shifted from a private school to a government school in his final year of high school. It shows that Kejriwal has been able to create opportunities for the youth,” Kanojia said, noting the improvement in standards in government schools.

“I will support him irrespective of whatever charges he is facing because they are unproven.”