Beijing migrant worker evictions: the four-character word you can’t say anymore

As the Chinese capital sets about evicting workers unfortunately described as the ‘low-end population’, two cornerstones of the country’s economic miracle seem to have come head to head: real estate and cheap labour

In the end, those four characters had to go, never to be seen or mentioned again: di-duan-ren-kou, or “low-end population”. A cold bureaucratic definition of low value-added manual jobs that somehow expanded to designate the people who do those jobs, has caused as much heartburn as the harsh spectacle of Beijing’s ongoing eviction of the people who fit that description. The censors have now banned that word from social media and elsewhere.

In an angry WeChat post, the writer-filmmaker Xu Xing said: “Low-end population – who invented those four characters? I’m over 60 and I’ve never heard anything like that. When I was in Germany it was a crime to use this expression.”

Tibetans to Sri Lankans, India welcomed all. Why not Rohingya Muslims?

“Migrant workers do not read government documents, so they had no idea that this is what they were called,” says Professor Jiang, an academic who studies the new Chinese working class and prefers to be referred to only by his last name. “Now they have discovered that they are second-class citizens.”

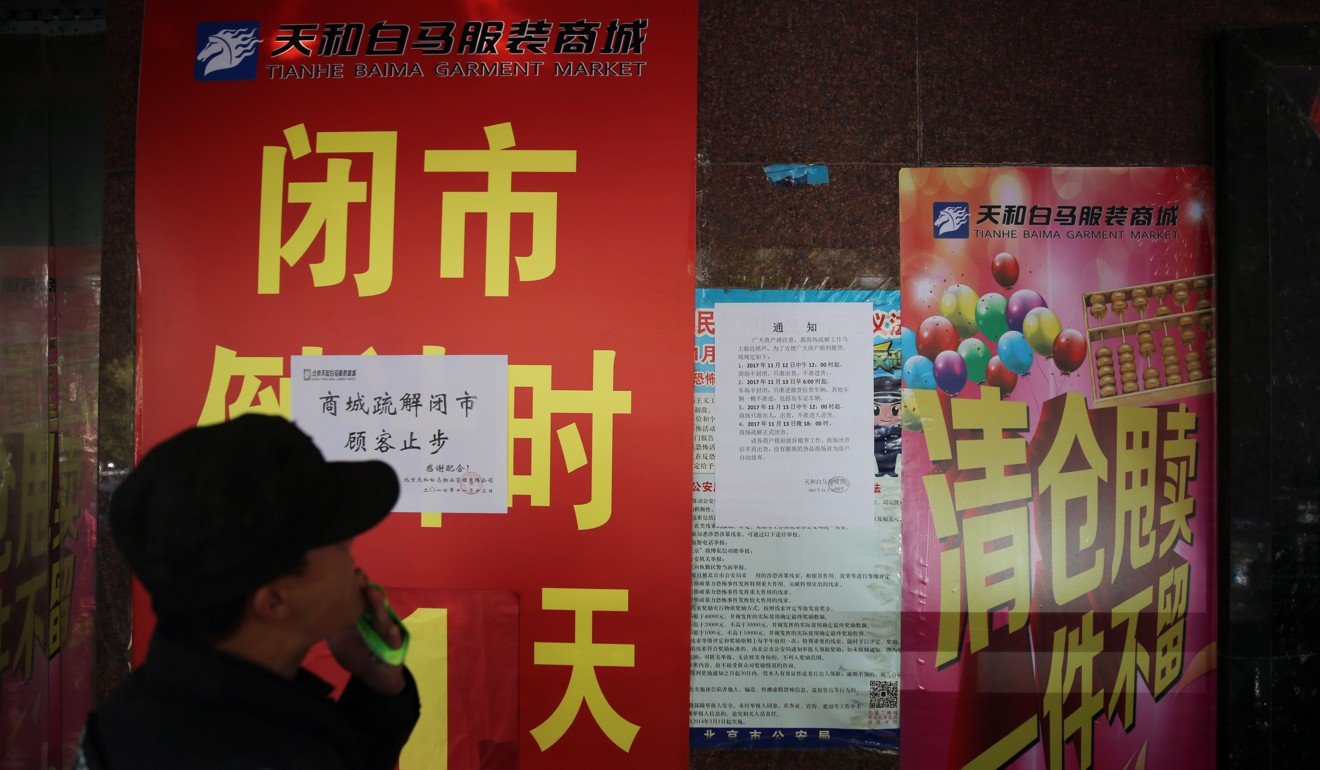

It all began on November 18, when a fire killed 19 migrants in the village of Xinjiancun – part of the southern suburb of Daxing in Beijing. The Beijing government immediately ordered a 40-day campaign to demolish thousands of unauthorised houses in the city and evict the migrant workers occupying these rickety premises.

The execution has been rapid and clinically efficient, wiping out whole neighbourhoods. Xinjiancun has been razed. A textile factory worker points to the rubble, saying many of her colleagues once lived right there. “Now they are theoretically still working here but they have lost their homes and disappeared,” she says. “They have to find their own housing now.”

The migrant workers falling into debt traps in Singapore’s casinos

In Picun, one of the villages in the northern belt of Beijing, officials used a softer strategy, but it hit just as hard in the biting cold. Power and heating were cut off in two buildings occupied by migrant workers. As one of the stated government goals is to reduce coal-fired homes, the authorities are entirely within their rights, no matter how ruthless it looks.

People are taking away their belongings, filing out through the dark and cold corridors. I try to engage a woman dragging away a suitcase, asking her how she feels being called “low-end”. She isn’t interested, and asks me to leave. Right now she doesn’t care what she is called – there are far more pressing matters on hand.

According to Jiang, what’s coming is a new wave of real estate speculation. In 2005, a resolution by the National People’s Congress identified 33 pilot counties, cities and districts that would have to “temporarily adjust and implement the Land Administration Law” while the authorities go about “getting the city into the countryside”, or turning rural land into attractive residential area. Daxing is one of those 33 pilot zones.

Whatever the official rationale for the eviction, Beijingers are perplexed at how these evictions in sub-zero temperatures could possibly be helping the cause of “harmonious” and “beautiful” China. And the drive is hurting them too. “They sent my ayi [housekeeper] so far away that now she has to travel two and a half hours to come to Beijing,” says a woman who lives near the second ring road. “What happens to the delivery boy who brings me the goods I buy on Taobao, or the guy who replaces the water tank in the office every day?”

Suddenly two cornerstones of the Chinese economic miracle seem to have come head to head: real estate and cheap labour.

Jiang thinks that sooner or later the government will establish quotas. “Maybe a certain number of ayi and delivery boys for a certain number of city dwellers, by area or zone. And maybe, those who remain will have a Beijing hukou [household registration] and decent and affordable accommodation.”

The others will go far, far away from Beijing. ■