How cricket bats for democracy in India

Levelling the playing field like little else, the ‘Indian game accidentally discovered by the British’ has become a metaphor for equality and hope

In India, a politician’s son or daughter has a fair chance of getting elected, a business house may actively promote hereditary succession and even the children of film stars can aspire and succeed on joining their parents’ profession, but a Test cricketer’s son cannot wear the India cap without being one of the 11 most talented players in the country. I am a living example of this. Famous surnames don’t work in cricket, that’s why there are no cricketing dynasties in India.

Seventy years after Indian independence, we could argue that cricket is one of the few largely meritocratic activities in the country, mirroring the idealism of our founding fathers and the spirit of our republican Constitution that sought equal opportunity for all. The cosy family networks, the privileges of the elite, the patron-client relations have been thwarted at the gates of a cricket ground: there is a democratic fervour that makes cricket the ultimate authentic Indian dream.

But it wasn’t always like this. Cricket in pre-Independence India started off as a colonial leisure sport to be played in the elite clubs of the presidency towns of British India. It was patronised by the princes and Parsee business elites who saw cricket as a passport to social mobility and a chance to earn the goodwill of the ruling aristocracy. The merchants and maharajas who were the early patrons played and supported the sport as part of their loyalty to the Empire and to signal their own superior social status – is it any surprise that the early royals who played cricket were all batsmen, with bowling and fielding looked at as menial tasks? Is it also any surprise that the first Indian team chosen to play England in 1932 had the Maharaja of Patiala as the captain and the Prince of Limbdi as his deputy?

It is purely fortuitous that the man who eventually led the Indian team for its first Test at Lord’s was not a royal but the greatest Indian cricketer of his generation: C.K. Nayudu, a “commoner”, became captain only because the Patiala ruler dropped out before the tour and the Prince of Limbdi was injured on the eve of the Test.

Indian cricket in its early years wasn’t just organised around feudalistic lines, but communal ones as well. The Quadrangular and Pentangular tournaments played in Mumbai in the early 20th century reinforced religious identities. Hindus, Muslims, Parsees, Europeans and The Rest (including Sikhs and Christians) had separate teams. The tournaments reflected a divided society that could not mount a unified challenge to the Raj.

Rage over mythical beauty Padmavati shows ugly side to a new India

Communal cricket at a time of nationalistic zeal was an abomination but it suited the “divide and rule” politics of the colonial rulers. Little wonder then that Mahatma Gandhi was disdainful of cricket. The Dalit community of untouchables, whose cause Gandhi fought for so assiduously, were first denied the right to play, and later were kept on the margins. Historian Ramachandra Guha, in his book A Corner of a Foreign Field, captures the plight of the first Dalit cricketer of repute, Palwankar Baloo, who was forced to sit apart from his teammates during the tea interval and drink from a disposable clay vessel while the others sipped their chai from porcelain cups.

Cricket then is Indian democracy’s alter ego, a metaphor for hope in a “new” and better India. When institutions of public life falter, the citizen turns to the cricket grounds for succour. As the ball soars skyward or the stumps are shattered, the flaws of nation-building seem inconsequential for a few seconds as we rejoice in the achievements of our homegrown heroes. There, on the field, as the 11 cricketers battle for India, Indians see reflections of their own struggles to make their way in their country, their disillusionment eclipsed and their optimism rekindled.

Hong Kong, like India, needs to remember the truth about British colonialism

Just as significantly, the sharp class divide that once threatened and even undermined Indian cricket in its early years has now almost entirely disappeared. Every year, the Indian Premier League (IPL) – the most lucrative cricket tournament in the world – makes stars out of talented young men from diverse backgrounds. In the 2017 IPL auction, for example, T. Natarajan, a young speedster from the southern state of Tamil Nadu, was offered a contract worth US$440 million (HK$3.44 billion). He is the son of a daily wage earner. So is Umesh Yadav, the spearhead of the Indian pace attack, from near the western Indian city of Nagpur.

Till the early 1960s, even Test players travelled across the country for international games by train (an exception was made for the first time in 1961-62 when India won a home Test series against England and the “reward” was an air ticket) and often stayed in cheap hotels. Now, of course, the top cricketers live in five-star luxury and could probably afford private jets!

Withdrawal symptoms: cash is still king in India, Modi not so much

The money-spinning IPL and the large and frenzied fan base has meant that India is now the capital of the global game. In September, the media rights for the IPL were sold to Star India for five years for an eye-popping US$2.6 trillion. Till the 1990s, some of the world’s best cricketers stayed away from playing in India, fearing disease. The likes of the English opening batsman Geoff Boycott, for example, were reluctant tourists to the subcontinent while the Australians toured India only once in the 1970s. Now the world itches to play in India, aware that this is the most profitable marketplace.

So how did cricket succeed where so much else has failed and help to unify a diverse society? Nelson Mandela said evocatively during the historic 1995 Rugby World Cup in South Africa on the power of sport to “unite people in a way that little else does”. That Rugby World Cup, when a post-apartheid South Africa cheered the victory of the country’s rugby team, until then a predominantly whites-only sport, unified a nation sharply divided by race.

Indian cricket has gone well beyond what a single World Cup rugby win achieved for South Africa in celebrating our oneness as a nation. Cricket is so dominant in the lives of millions of Indians that sociologist Ashis Nandy wryly remarked, “Cricket is an Indian game accidentally discovered by the British.”

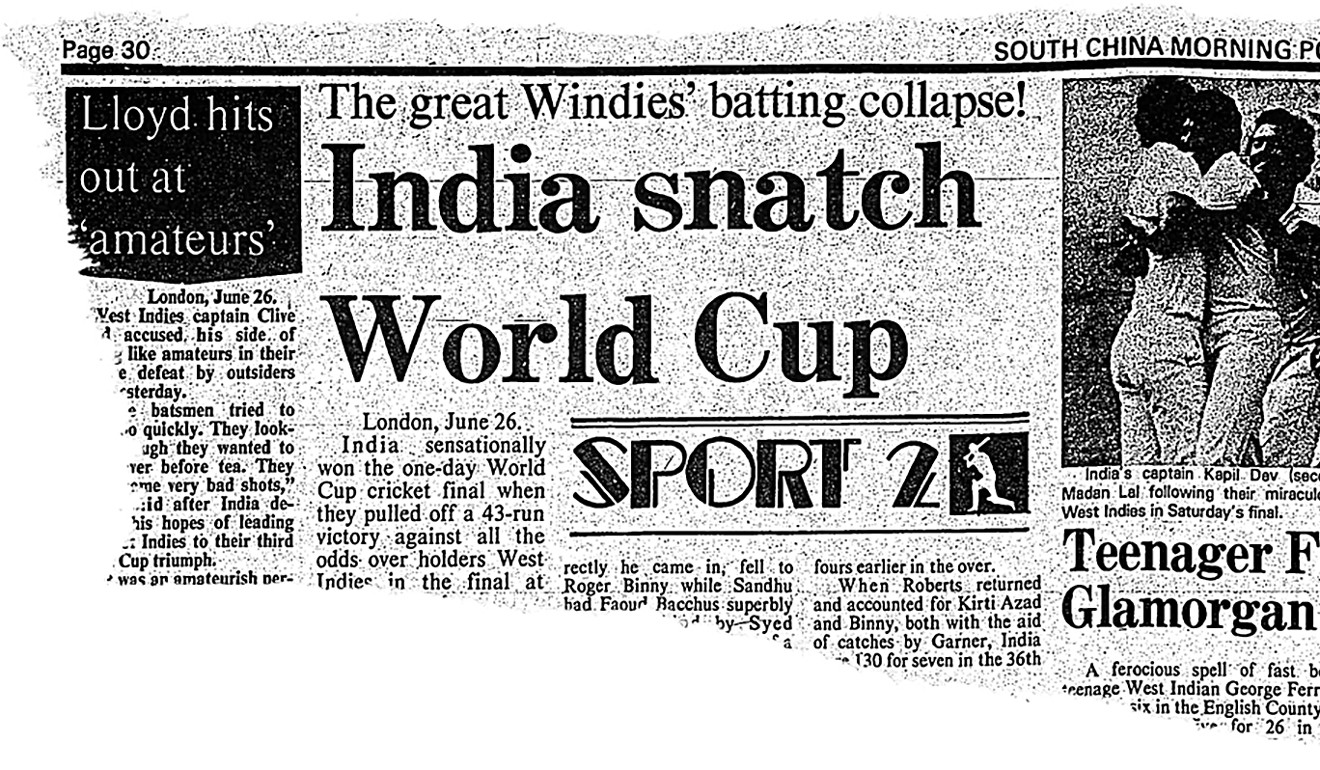

How did cricket transform from an elite sport into a mass spectator sport, from recreation for the privileged into an inclusive national “religion” where cricketers are our modern-day divinities? There are, to my mind, four turning points in India’s post-independence cricket history.

What a controversy over the Taj Mahal says about a changing India

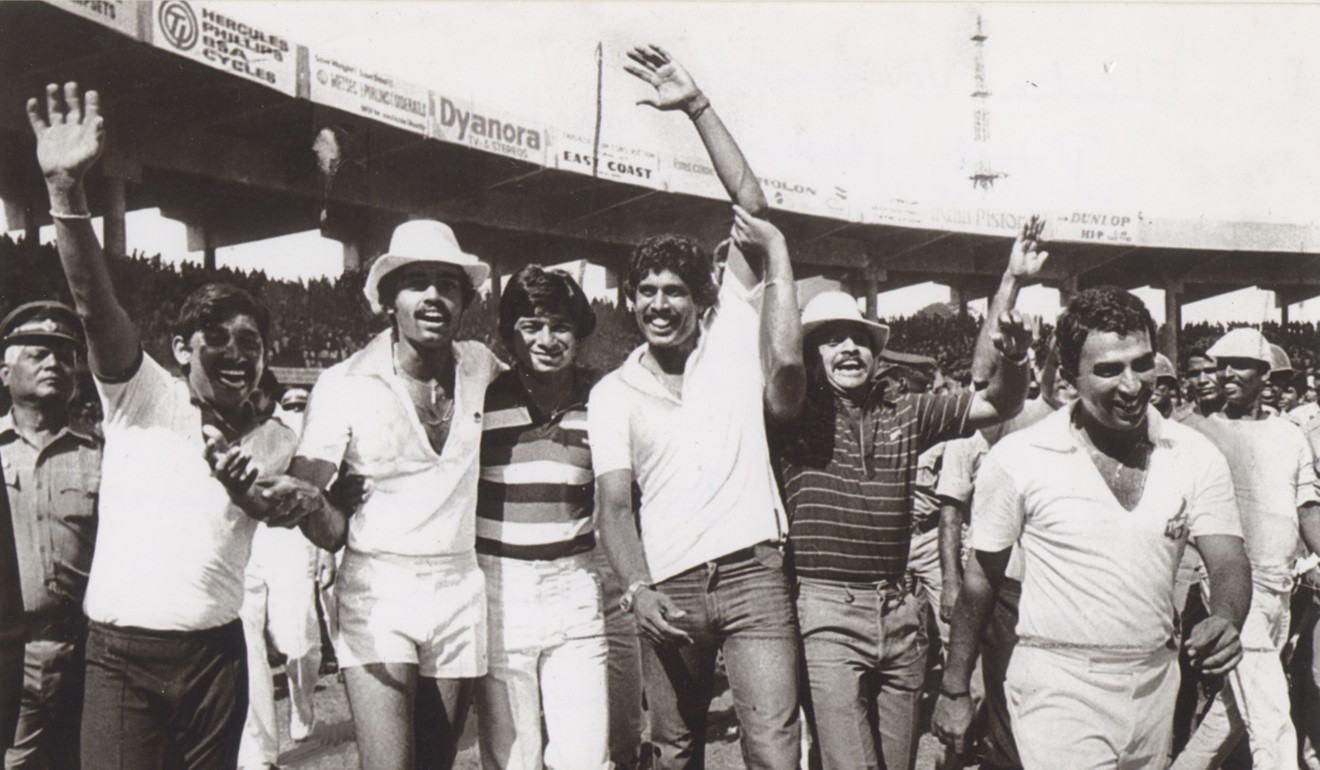

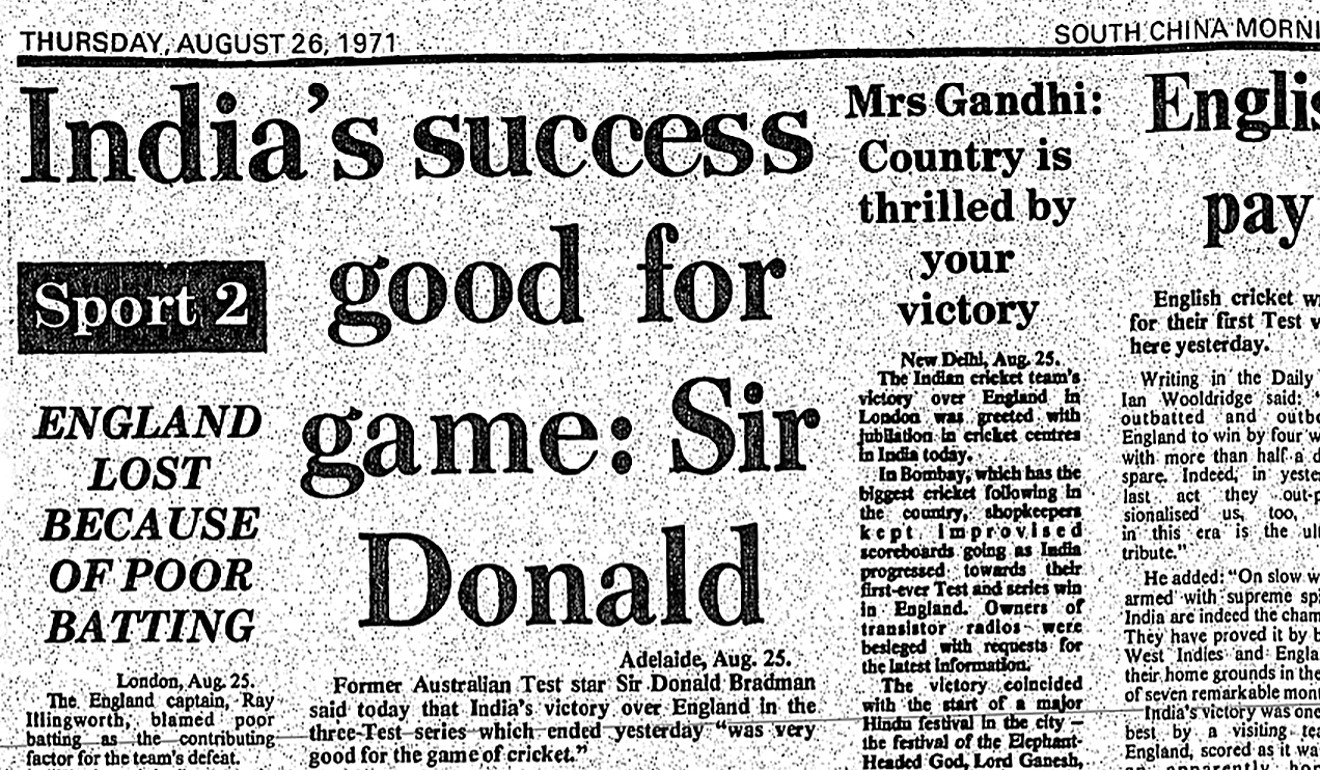

The first is in 1971, when the sport was liberated from the Empire, cricket’s equivalent of the freedom at midnight moment of 1947. It was the year India scored overseas victories in the West Indies and England for the first time, instilling a self-belief in Indian cricket. For an adolescent nation struggling to assert itself, the cricket wins of 1971 can be likened to the famous victory the same year in the battlefield over Pakistan that led to the formation of Bangladesh, to the Green Revolution that made India self-sufficient in foodgrain, the space programme that launched indigenous satellites, and the 1974 nuclear tests. Each of these landmark achievements gave nationhood a boost and fulfilled a young country’s yearning for self-reliance.

The third defining moment was the opening up of the Indian markets in the 1990s. Economic liberalisation saw the unshackling of Indian entrepreneurship, allowing cricket to be a major beneficiary from the sudden spurt in the consumer goods market and an exponential rise in advertising revenues on cable and satellite television. Every match was now telecast live on private channels as the Supreme Court ruled in 1995 that airwaves were no longer a government monopoly. The financially successful 1996 World Cup played in the subcontinent showed the balance of cricketing power was shifting from West to East.

Modi’s theatrics ring hollow to victims of India’s anti-Muslim mobs

Four years later, India lifted the 2011 World Cup on home soil. If 1983 was a bit of a fluke, 28 years later, the victory at Mumbai’s Wankhede stadium in front of the country’s largest-ever television audience only confirmed India’s status as a 21st century cricketing superpower. This year, India was formally anointed the No 1 Test side, officially cementing its status.

It is in tracing this amazing rise of Indian cricket and how it links to strengthening a sense of nationhood makes the stories of those who shaped the game so exciting. And it is these stories that are a part of the romance of Indian cricket, which continues to inspire and motivate millions of Indians to dare to dream. ■

This is an extract from journalist and author Rajdeep Sardesai’s ‘Democracy’s XI: The Great Indian Cricket Story’, which traces how Indian cricket and society have evolved since the country’s independence in 1947