Special report: how Canadian immigration fraud saw 860 rich Chinese blacklisted

How policymakers ignored alarm bells for years about a systemic flaw in the world’s biggest wealth migration system

On the morning of October 17, 2012, Canadian border agents began their raids simultaneously, targeting offices in downtown Vancouver and nearby Richmond, as well as a large house on a busy arterial road.

They seized 90 crates of documents and 18 computers, stacks of supposedly “lost” Chinese passports, even a handful of red rubber stamps. There was so much evidence it would take more than a year to translate and organise.

Anatomy of a scam: how rich Chinese gamed Canadian immigration

The vast haul, seized from unlicensed immigration consultant Xun “Sunny” Wang, would send shock waves through the lucrative arena of millionaire migration, and in 2015 sent Wang to prison, for scams that had earned him C$10 million (US$7.6million). Sentenced to seven years’ jail, Wang was paroled late last year, having served a third of his time.

But an investigation by the South China Morning Post – based on dozens of court and immigration hearings, as well as on interviews with lawyers, tax auditors, officials and industry veterans – shows that the scandal of the biggest immigration fraud in Canadian history is far from over.

And the story began years before officers pulled up outside Wang’s home.

Canada’s border authority told the Post at least 860 clients of Wang’s firms, New Can Consultants and Wellong International Investments, had already either lost immigration status – resulting in expulsion and five-year bans from entering the country – or been reported for inadmissibility.

Resolved cases reveal the privileged lives of the Chinese millionaires whose presence in Canada Wang fabricated with fake addresses and jobs, allowing them to maintain permanent residency or obtain citizenship when, in fact, they lived most of the time in China.

By their very nature, these are individuals who are not inclined to stay in Canada. They have lives and businesses in China

Yet there had been warning signs for years about the endemic failures in Canada’s wealth migration system that allowed Wang’s scam to flourish.

The little-remembered case of the disgraced immigration lawyer Martin Sheldon Pilzmaker rocked Canadian legal circles in the late 1980s.

It featured a cast of foreign millionaires and a rule-breaking advocate who would fix their immigration woes, as he cruised Toronto’s Bay Street in a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce. His tactics and his Hong Kong clients’ motives offered a near-perfect template for the Wang case.

Instead of jail, Pilzmaker’s adventures in the world of wealth migration ended 27 years ago with his suicide in a cheap hotel.

The implications of his lurid case would go ignored by policymakers for decades, as waves of wealthy newcomers helped Canada dominate the global millionaire migration industry and reshaped parts of the country, particularly the west coast city of Vancouver.

The fraud employed in the Wang case “is old hat” said one 30-year veteran of the industry, pointing to the Pilzmaker scandal. “It’s been going on ever since we’ve had business immigration.”

How China’s Polar Silk Road can make Canada the next big Asian power

He and other insiders said both cases exposed the foundational flaw in the premise of millionaire migration: the widespread unwillingness of breadwinners in such households to actually live and pay tax in Canada. Their observations are also backed by years of tax and immigration statistics.

“What’s the main reason [for the Wang case]? Well, it’s the fiction that wealthy immigrants are going to come here and do a lot of business here … Wealthy immigrants have no interest in that. They want to park their wives and kids here.”

Among Wang’s ex-clients, case after case tells that very story – salted with various eye-popping details.

There is the wealthy Beijing lawyer and his family who returned to China just 10 days after activating permanent residency in Vancouver. There is the investor with five homes in Canada, who still lived in the mainland because he claimed Chinese custom required him to mourn his dead mother in her home village for three years.

There is the millionaire who declared his entire worldwide income as C$720 in Canadian childcare benefits, but who sent his student daughter C$61,000 to buy a Mercedes-Benz in Vancouver that year.

New cases continue to emerge, as Wang’s 1,600-plus clients are checked off against a list when they arrive at Canadian airports, according to a lawyer for one.

“By their very nature, these are individuals who are not inclined to stay in Canada,” said the lawyer, who declined to be identified. “They have lives and businesses in China.”

The rise and fall of Martin Pilzmaker

An open packet of cigarettes sat on a window ledge outside the front door of Wang’s house in south Richmond – the same property where at least 20 of his clients once fraudulently claimed to reside.

The home, built in 1990 in gauche Palladian style, looks dated now with its five-metre columns and salmon paint. It is nevertheless worth C$1.5 million.

When the Post knocked on a recent Sunday, the curtains flickered and someone peeped outside. But no one came to the door. A written request for Wang to contact the Post went unanswered, although he was recently spotted leaving the home by broadcaster Radio-Canada.

For Wang, his return to the scene of the 2012 raid brings him full-circle.

There would be no such closure for Martin Pilzmaker.

David Lesperance, a former border officer at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport, had just started out in his new career as an immigration lawyer when the scandal was hitting headlines.

It was the talk of the industry – one day in the early 1990s, a wealthy Hong Kong immigrant turned up at Lesperance’s office, asking if anyone knew how to find Pilzmaker, from whom he expected delivery of a Canadian passport. It was left to Lesperance to deliver the double blow that Pilzmaker was dead, and it was unlikely the immigrant would be getting his passport any time soon.

As Lesperance digested the case: “Things that I was seeing when I was a border official all of a sudden started to make sense.”

Pilzmaker had been called to the bar in 1977, but his story really begins with the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong, sealing the territory’s return to Chinese rule in 1997 and triggering a rush for foreign passports that would make Pilzmaker rich.

Pilzmaker was one of the first to recognise the lucrative potential of millionaire migration out of Hong Kong. His solo practise was booming when he set his sights on a partnership with a Bay Street firm in Toronto, the top tier of Canadian legaldom.

Rhodes scholar Philip Slayton recalled Pilzmaker applying for a job at Blake Cassels & Graydon, where Slayton worked. His demands “were hard to swallow”, Slayton wrote in his book Lawyers Gone Bad, in which he described Pilzmaker wearing a C$20,000 fur coat.

“Pilzmaker wanted an immediate partnership, a big share of the profits, and a corner office. Blakes … would also have to pay for the chauffeur of his Rolls-Royce Corniche convertible.”

Rejected by Blakes, Pilzmaker was recruited instead by Lang Michener in 1985. He was just 37, but in his first year he received full partnership and an astonishing C$400,000 starting salary – his stablemate at the firm, the future Canadian prime minister Jean Chrétien, had to settle for C$100,000.

The flashy Pilzmaker was an awkward fit at a practice described as the “government in waiting”, so packed was it with Liberal Party elites. But “they were ready to hold their noses and suffer Pilzmaker’s crude conduct for an entry into the teeming Pacific Rim,” wrote investigative reporter Victor Malarek, in an account of the scandal in his 1996 book Gut Instinct.

The new recruit was an immediate success, bringing more than C$1 million in business in his first year, the Toronto Star later reported.

It was too good to be true.

They were ready to hold their noses and suffer Pilzmaker’s crude conduct for an entry into the teeming Pacific Rim

Pilzmaker clients’ initial preferred pathway was via an entrepreneur immigration scheme. Then in 1986, Canada launched its Immigrant Investor Programme (IIP), in which applicants selected by wealth benchmarks paid for permanent residency via government-approved investment, initially C$150,000.

It was the world’s “first true residence by investment programme”, according to the Global Investor Immigration Council.

The industry exploded, and Canada found itself at the forefront of an immigration gold rush.

By 1996, the federal IIP and its Quebec variant would bring more than 57,000 rich immigrants to Canada, about half from Hong Kong and a further 20,000 from Taiwan.

But Pilzmaker – like Sunny Wang decades later – recognised the flaw in the basis of wealth-determined migration.

Saudi Arabia brings gun to knife fight with Canada over Samar Badawi … déjà vu, China?

Although applicants coveted Canadian citizenship and residency rights as a potential escape route for their families, they were unwilling to actually live, work and pay much tax in Canada.

Pilzmaker offered a solution. He bought three houses in Toronto to help fabricate backstories for his clients. The addresses were used to obtain local driving licences and utility accounts in their names. Bills and other official documents addressed to his clients provided fake proof of residency.

In Business & Professional Ethics for Directors, Executives, & Accountants, by Leonard J Brooks and Paul Dunn, Pilzmaker’s deceptions are fleshed out – becoming a literal textbook case of immigration fraud.

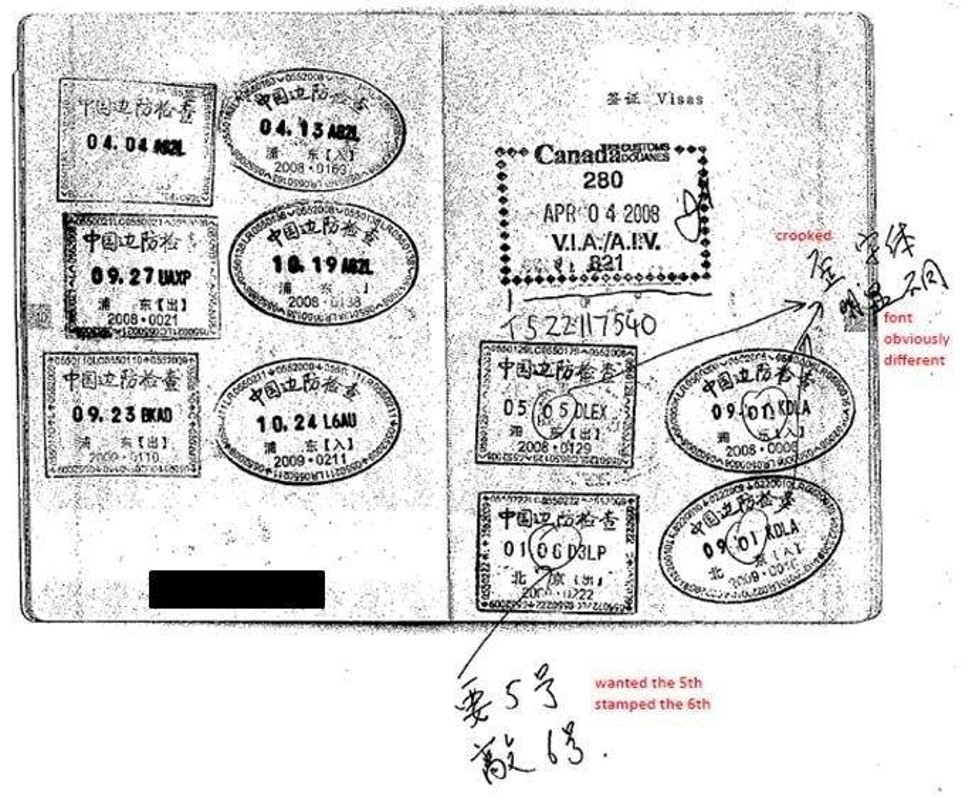

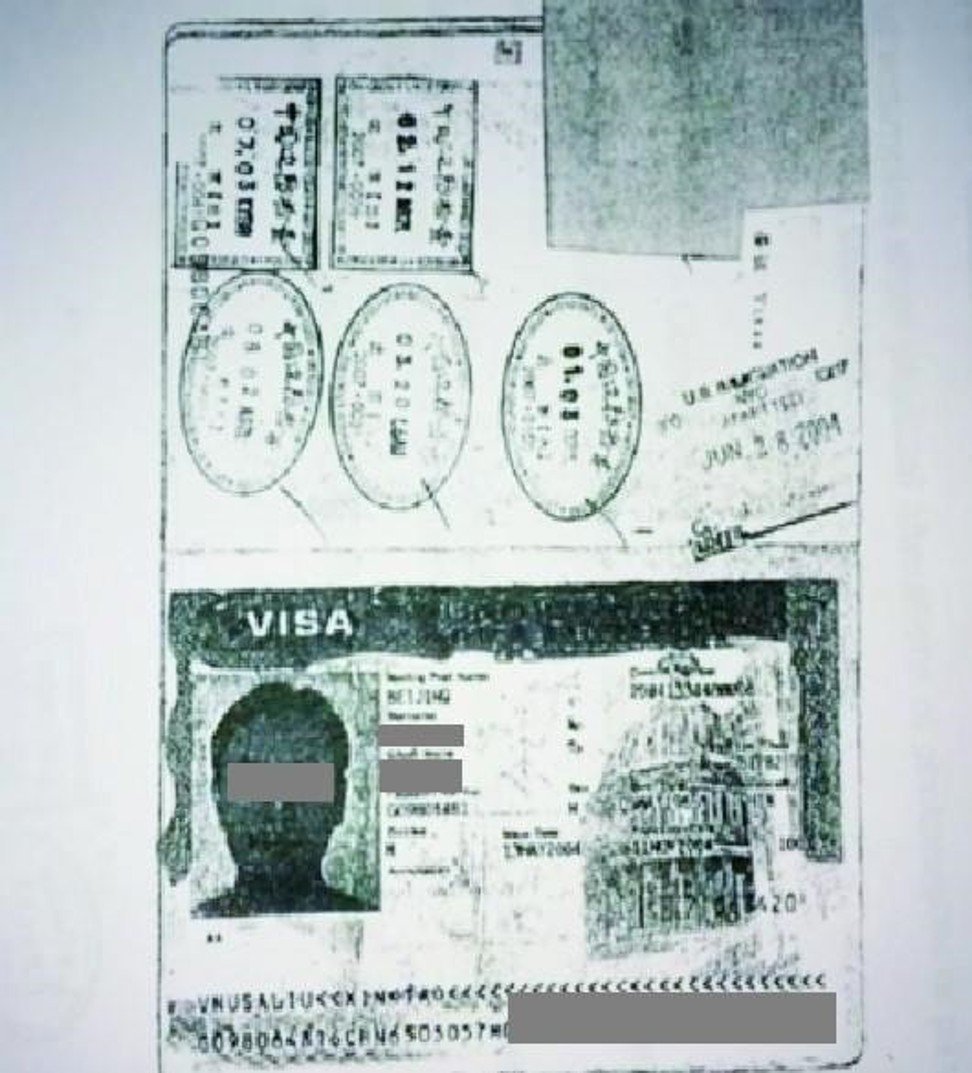

Citing Law Society proceedings, it recounts how Pilzmaker’s juniors confessed in 1986 to Tom Douglas, a senior colleague at Lang Michener, that Pilzmaker “was running a double-passport operation”.

“The scam involved the false reporting of lost Hong Kong passports by his clients, which, in fact, would be kept by Pilzmaker in Canada,” the book recounts, paraphrasing Douglas.

“On their replacement passports, the clients could travel in and out of the country at will. When the time came to apply for citizenship … they could supply the original ‘lost’ passports to show few if any absences from Canada.”

On June 8, 1988, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police raided Lang Michener’s First Canada Place offices, seizing files on 149 of Pilzmaker’s clients.

The Law Society found five Lang Michener partners guilty of misconduct in 1990 for their handling of their rogue colleague.

As for Pilzmaker, he was charged with more than 50 immigration offences in July 1989, then disbarred on January 25, 1990, and declared “ungovernable”.

Fifteen months later, freed on C$75,000 bail, and with his criminal trial scheduled to begin in a fortnight, Pilzmaker checked into The Cromwell hotel flats on Isabella Street in downtown Toronto.

There he was found dead, next to two empty pill bottles, on April 19, 1991.

Warning bells and the ‘complete fantasy’ of millionaire migration

In legal circles the recriminations of the “Lang Michener Affair” went on for years, damaging the reputation of Chrétien and others and raising questions about the governance of lawyers.

But for immigration policymakers it was as if the scandal, with its obvious implications for the booming millionaire migration industry, never occurred.

The reluctance of rich immigrants to physically relocate and declare all worldwide income to Canada – Lesperance terms them “ghost immigrants” – seemed almost universal.

“It wasn’t a function of nationality of the immigrants … it was simply the target market,” said Lesperance, describing how the problem was as common among Hongkongers fleeing in the wake of the Tiananmen Square massacre as it was among millionaires from the Middle East after the first Gulf War.

In Vancouver, long favoured as the primary destination of millionaire migrants in Canada, these tendencies would fuel the phenomenon of astronaut families, whose primary breadwinners return to their place of origin. Peer-reviewed research has linked undeclared foreign earnings and immigrant wealth to the chronic detachment of property prices and local incomes in the city, now one of the most unaffordable in the world.

Obscuring this tendency of his clients to live in China – while claiming residency in Canada – formed the entire basis of Sunny Wang’s services.

One client, investor migrant Xi Wen Dai, 61, repeatedly described Canada as home as he fought an exclusion order. But he had spent just 33 days in Canada in the five years prior to his appeal, which was rejected by the Immigration and Refugee Board in April 2017. “China is and always has been his home,” said IRB panellist George Pemberton.

Xi claimed his lengthy absences from Canada were due to a tradition demanding three years of mourning the death of his mother – in her Chinese home village. That “is beyond the norm of what I can reasonably take notice of as cultural practice”, Pemberton said.

In 1991, soon after Pilzmaker’s death, Lesperance testified in Ottawa to a parliamentary subcommittee on immigration, laying out the quandary posed by ghost immigrants. But the parliamentarians, he said, subscribed to the image that rich immigrants wanted to come to Canada to “rub shoulders with everyone in Canadian Tire and Tim Horton’s”. It was, he said, a “very nice, complete fantasy”.

They were also ignorant, he said, of the situation’s impending scale. “They didn’t see the tidal wave coming,” said Lesperance.

Passports for sale: why rich Chinese are the new super immigrants

Combined, the entrepreneur and investor schemes would eventually bring about 400,000 rich newcomers to Canada, although the federal IIP and the entrepreneur scheme were shut down in 2014. The QIIP, now priced at C$1.2million in loans to the provincial government, is still scheduled to bring in 1,900 millionaire households each year.

It wasn’t just Lesperance raising concerns.

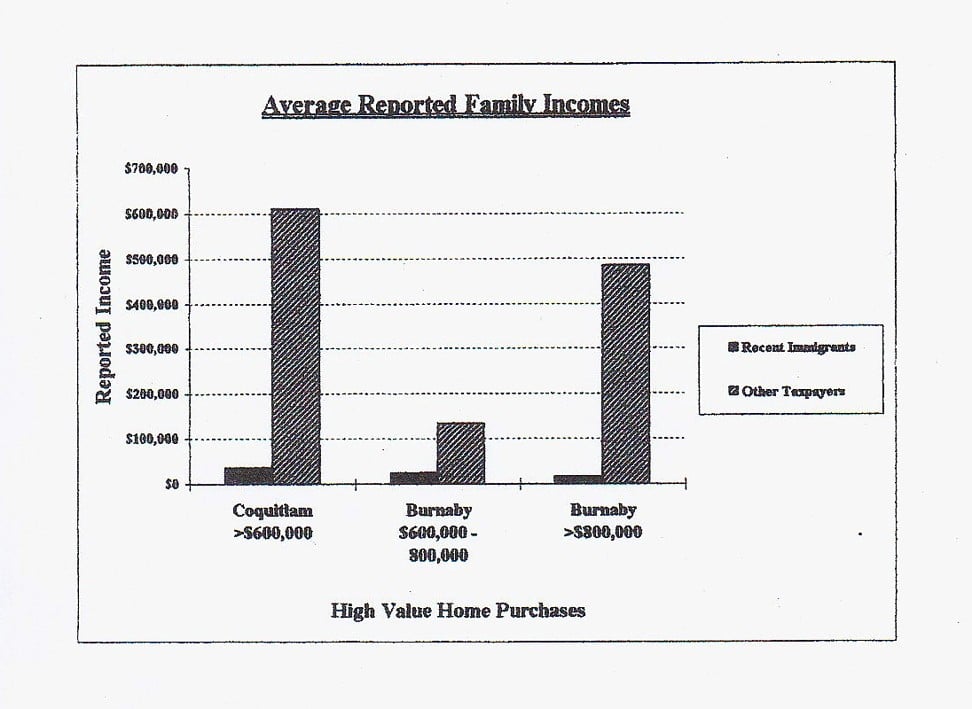

In 1995, a team of Canada Revenue Agency auditors in greater Vancouver began investigating 200 immigrant investors on a client list obtained from one of the funds that were then linked to the scheme.

“The results were worse than we thought,” said one of the auditors – now retired from the CRA but requiring anonymity because of their current employment. “Even though many of the investors had not even filed income tax returns, not one of the investors that filed tax returns reported any business income, or income from offshore sources such as salary or dividends.

“Only Canadian interest income and government family allowance income was reported. So no taxes were paid, and certainly no worldwide income from persons who supposedly had businesses located overseas.”

Those investigated were mostly in their 40s and 50s – “their prime income earning years”.

The auditors then examined the lifestyles of the 200 migrants and “immediately recognised that many of them had purchased homes in the wealthiest neighbourhoods in various parts of Vancouver”.

The results were sent to CRA bosses in the hope of triggering a major investigation of investor migration. “The thought process was that this factual info could shock local senior management and management in Ottawa of the gross misrepresentation of reported income by these very wealthy people,” the retired auditor said.

But few official audits were launched – and those that were resulted in drawn-out court battles with well-financed opponents. Because of the huge manpower required to audit unidentified global income – versus, say, a local Canadian business – tax recovery was minimal compared to the effort.

Auditors were keen to pursue immigrant investors as a matter of law enforcement and principle, but as a revenue raiser, bosses saw the project as a bust.

There was “not enough leadership or recognition of the magnitude of the non-compliance from top management … the screened files got swept under the carpet”.

Ten years after admission, a 2014 federal government evaluation showed, average annual income tax being paid by IIP breadwinners was C$1,400 (one-fifth that of the average taxpayer, and one-eighth that of skilled-worker immigrants). Their annual taxable income from all sources peaked at just C$19,500 three years after arrival, then defied the trend of all other immigrant classes by falling sharply, to C$15,800 after 10 years.

The failure for more than 30 years to systematically investigate the suspiciously low incomes endemic to wealth migration remains a source of regret among CRA staff: three current and former auditors helped the Post with its 2016 investigation.

“I spoke recently to a retired CRA real estate appraiser, who said ‘we missed the first wave in the ’90s, then the wave in the 2000s, now we have gone through another wave, and we still have no handle on it’,” said one of them. “You’d think we, or the politicians, would have it figured it by now.”

An associated phenomenon is the chronically low retention rate of IIP and QIIP, another tendency exploited by Wang and Pilzmaker.

Census and immigration data show more than 40 per cent of IIP principal applicants do not live in Canada; the true figure is likely higher, since it excludes people who deceptively claim physical residency. It is, nevertheless, the worst in-Canada retention rate among all immigrant classes.

A 30-year veteran of the Canadian immigration industry, now retired, said that low retention of millionaire migrants suggested illicit services like those provided by Wang would be commonplace.

“It’s the same pattern that’s been going on for 30 years now,” he said, drawing a direct line between Pilzmaker and Wang, both of whom were “fabricating indicia of presence in Canada when in fact [their clients] were not here”.

“It goes way, way, way back and it’s part of the same phenomenon that we see with Hong Kong and Taiwan and now mainland Chinese – mostly business immigrant – families, where the head of the family has no interest in immigrating to Canada at all. He wants to continue running his business in China, or wherever.”

This was not a specifically Chinese behaviour but was instead typical for the rich, with profitable businesses and high-paying jobs in their country of origin. “They are the ones with the incentive not to actually live in Canada,” the immigration expert said.

One such client of Wang, millionaire businessman Pi Long Sun, had only visited Canada twice since 2012. However, he continued to file his taxes in Canada, listing his entire worldwide income in 2015 as C$720 from Canada’s Universal Child Care Benefit.

“In that year [Wang and wife Ying Wang] paid for their children’s living expenses in Canada, university tuition at the University of British Columbia for [their eldest daughter], private school tuition for their youngest daughter, and C$61,000 cash for a Mercedes-Benz [for their eldest daughter],” said IRB panellist Pemberton, as he denied the couple’s appeal against exclusion last year.

The downside of this general phenomenon was not just the loss of tax revenue, and the compromised integrity of Canadian residency and citizenship, added the retired CRA auditor. “They do not report their income while taking full advantage of our social programmes and boosting the value of real estate,” he said.

These included Xiao Qing Li, who lost an appeal against exclusion in June 2017. She and her husband, a partner in a Beijing law firm, had returned to China to live just 10 days after activating Canadian permanent residency in 2006.

In 2014, Li and the couple’s two sons did indeed move to Canada, where Li claimed benefits based on her status as a low-income worker, in a fake job arranged by Wang.

Her West Vancouver home was valued at more than C$8 million. Other Canadian properties boosted the family’s net equity position to “well over C$10 million”, according the IRB ruling against her.

The legal wreckage left in Wang’s wake

Vancouver immigration lawyer Peter Larlee is busy these days, as he cleans up after Sunny Wang.

He has represented about 50 ex-clients of Wang, about 35 of whom have already lost residency status and been issued five-year exclusion orders. Other cases are pending, while three have been successfully appealed.

“I really feel for my clients because a lot of them were so poorly served by Wang. They were led into a type of behaviour that is not condoned in our society, signing blank forms, leaving it all up to someone else to do,” Larlee said. “But we all tend to fall into that. I mean, if you go into a lawyer’s office you put your trust in someone, and they put their trust in the wrong people.”

He said his clients were “seduced” by the simple solution offered by Wang to their common immigration plight: they failed to spend enough time in Canada to maintain permanent residency (currently, two years within a five-year period).

Like Pilzmaker, Wang’s business model, branded “sinister” by one judge, was to fabricate his clients’ presence in Canada. Travel dates would be changed or added to passports with the help of fake stamps and Chinese forgers. Passports would be reported lost, but instead couriered to Wang for doctoring.

Properties in Calgary and Edmonton as well as Wang’s own Richmond home were used as fake addresses for Wang’s clients, who were given backstories that included official correspondence and jobs with fake businesses. Some were issued payslips that allowed millionaires living in China to claim tax benefits intended for poor Canadians.

“What we can tell you, is that [as of March], over 860 of New Can Consultants Ltd and Wellong International Investments Ltd clients have either lost their status or been reported for inadmissibility under the Immigration and Refugee Act,” said a spokesman for the Canada Border Services Agency. “To date, over 55 of these clients have been removed.”

The CBC has reported that more than 200 others face the potential loss of their Canadian citizenship.

Larlee said he had suspicions about how some immigration consultants were operating in Vancouver before news of the Wang scandal broke.

“I knew that there was at least one consultant who was openly advertising that PR card renewal could be obtained even with long absences. Some [potential clients] asked why I couldn’t do it. I said it wasn’t possible and they should be very cautious.”

A small number of Wang’s customers appear to have had genuine cases to stay in Canada. But the immigration status of many hundreds more has been denied or is in peril.

One Vancouver-based lawyer, who represents several of Wang’s clients and requested anonymity, said: “The notorious astronauts who come over and drop off their families and go back to China … they just don’t stand a chance.”

He was advising such clients to swiftly concede the allegations against them, resulting in a five-year ban from visiting or applying to move to Canada. “You want the penalty period to start as soon as possible,” he explained.

The lawyer said the CBSA was still identifying suspects at Canadian airports, using a “very convenient list” seized from Wang’s home.

“So it was pretty easy to take that list and just create a bunch of red flags for all these individuals … My guy was grabbed just the other day. So they’re still doing it. They’re still catching people as they come in.”

The bid to expand millionaire migration and ‘placate concerns’

Even as Wang’s clients wend through the legal system, some in Canada’s immigration industry eye that pool hungrily, as they pursue the revival of the federal millionaire migration scheme.

“Launching a new federal immigrant investor programme could draw more foreign capital to Canada to support such key areas as infrastructure, affordable housing, and venture capital,” wrote the board’s Kareem El-Assal, the summit organiser, in a report summarising the event.

Vancouver immigration lawyer Jeffrey Lowe suggested to attendees that a new IIP could require applicants to fund affordable housing with investments of C$1.5 million.

Retention of IIP immigrants had been a pervasive problem, Assal’s report acknowledged, while the board noted in a news release that “a public awareness campaign would also be required to placate concerns regarding the impact of immigrant investors on real estate prices in major cities such as Vancouver”.

Another investor immigration summit is planned by the board in Ottawa this November, by “popular demand”. Guests are slated to include government ministers.

He agreed that ignoring physical presence was a tough proposal to sell to critics, who would respond “‘well, that’s un-Canadian’, and that’s where the conversation ends”.

“But [instead] you keep doing the same thing, and you expect a different result? That’s madness,” said Lesperance. He derided physical presence rules as a “wish list”. “And people quickly discovered it was not enforceable, so they ignored it.”

Wang and his clients were at least partly enabled by the “incompetence” of border authorities, said one immigration lawyer. “I find it hard to believe that if you use the same address on repeated applications for so long, that no one’s going to notice it,” he said.

But Peter Larlee, his law office inundated by the aftermath of Wang’s activities, described an encounter that highlighted the fundamental mindset problem among many millionaire migrants.

“I met with clients who wanted to renew their permanent resident card and I put it to them like this. I said: ‘Well, I know how you can renew your permanent resident card’,” he recounted.

“And they said, ‘Oh great, please tell me, share with me your wisdom’. I said, ‘Stay in Canada.’

“‘No, that’s preposterous. I can’t do that’. And they jumped out of their chair and they went away. I suspect people like this went to Sunny Wang’s office.”

None of Wang’s clients named in this article, all of whom were approached via their lawyers, would speak on the record.

Click here for compiled case studies of Sunny Wang’s clients