How Singapore made a giant of Chinese art, Chen Wen Hsi

- Guangdong-born artist Chen Wen Hsi forged a new kind of East-meets-West art when he emigrated to Singapore

- An upcoming exhibition at his US$11 million former home in Bukit Timah showcases his unique legacy

Bukit Timah is a swish Singapore neighbourhood where an inordinate number of roads are named after the kings, queens, duchesses and dukes of the former British Empire. A blue plaque on a bungalow at 5 Kingsmead Road, however, commemorates a different kind of history.

The plaque is bestowed by Singapore’s National Heritage Board, and although the round blue sign is discreet, its presence denotes a singular honour: this house is the only private residence in the country designated a historic site. It’s because it previously belonged to pioneering Singaporean artist Chen Wen Hsi.

Born in Guangdong in 1906, Chen arrived in Singapore in 1947. He is a key figure in the Nanyang movement: a group of emigrant artists who fused traditional Chinese art training with Western styles and techniques such as Post-Impressionism and cubism. The work of these artists today attracts keen and growing interest among Asian collectors, with Chen’s oil on canvas painting Pasar fetching a record HK$13.24 million (US$1.7 million) at a Sotheby’s Hong Kong auction in 2013.

From the early 1960s until his death in 1991, Chen lived at 5 Kingsmead Road. For decades, he taught art at The Chinese High School, which was nearby, and also held lessons in this house; in the garden, he kept a menagerie of animals, to better capture their essence in his paintings.

The 19th-century Chinese cartoons with a revolutionary message for Singapore

Evidence of his experiments in abstractionism can be seen in the form of two murals on the front porch, created in 1960. The house sat empty for several years after his death, and by the time artist Tay Joo Mee bought the property in 1998, the murals were overgrown with algae.

Tay had met Chen years ago, and bought some of his paintings. Her appreciation of his work inspired the preservation of aspects of his legacy. Before the house was redesigned, stacks of Chen’s paintings were discovered in the attic. These were handed over to his family. Tay also made sure the murals were carefully restored.

The house has changed hands once again, and she will be moving out later this year. New owner Audrey Koh Karmen, a psychotherapist, bought the property for S$15 million (US$11.1 million) and plans not only to preserve Chen’s murals, but also to incorporate them into the design of her new house so that the murals will be more visible from the main road. “I feel a responsibility to keep these murals for the next generation,” she says.

Before that happens, members of the public will have a chance to view a range Chen’s work in his former abode. From April 12-May 3, this will be the site of Homecoming: Chen Wen Hsi Exhibition @ Kingsmead, which will showcase more than 30 of his Chinese ink paintings.

Most of these are from the private collection of Johnny Quek, a former civil servant and 25-year director of the Merlin Gallery. Quek befriended Chen in 1978 and has amassed more than 600 of his Chinese ink paintings. His admiration for Chen’s unique sensibilities is infectious.

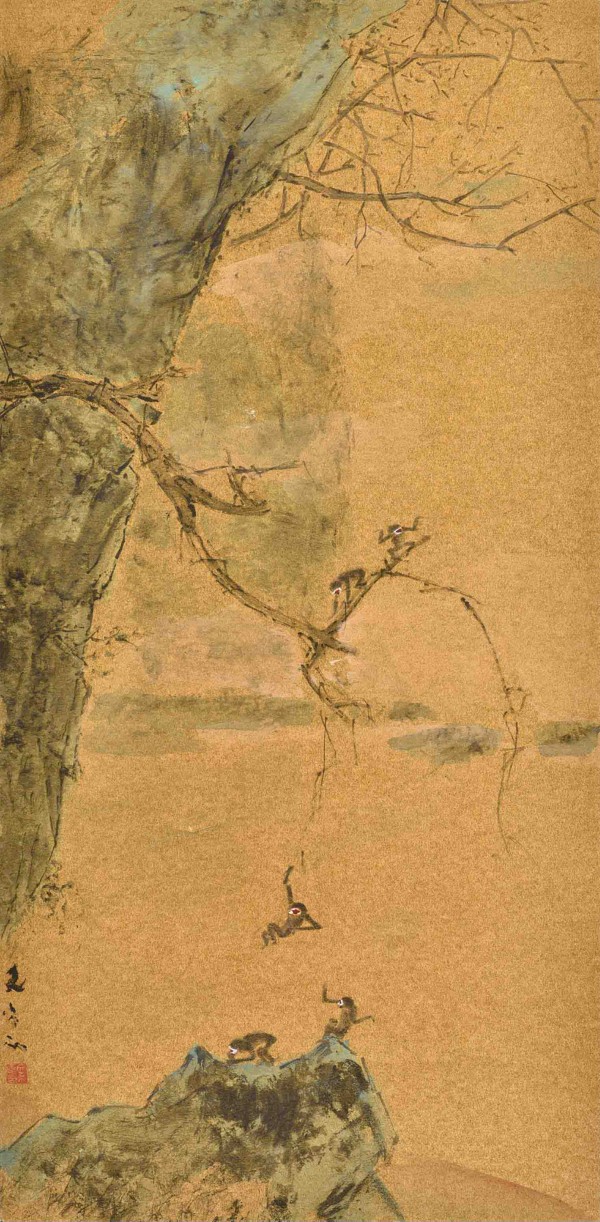

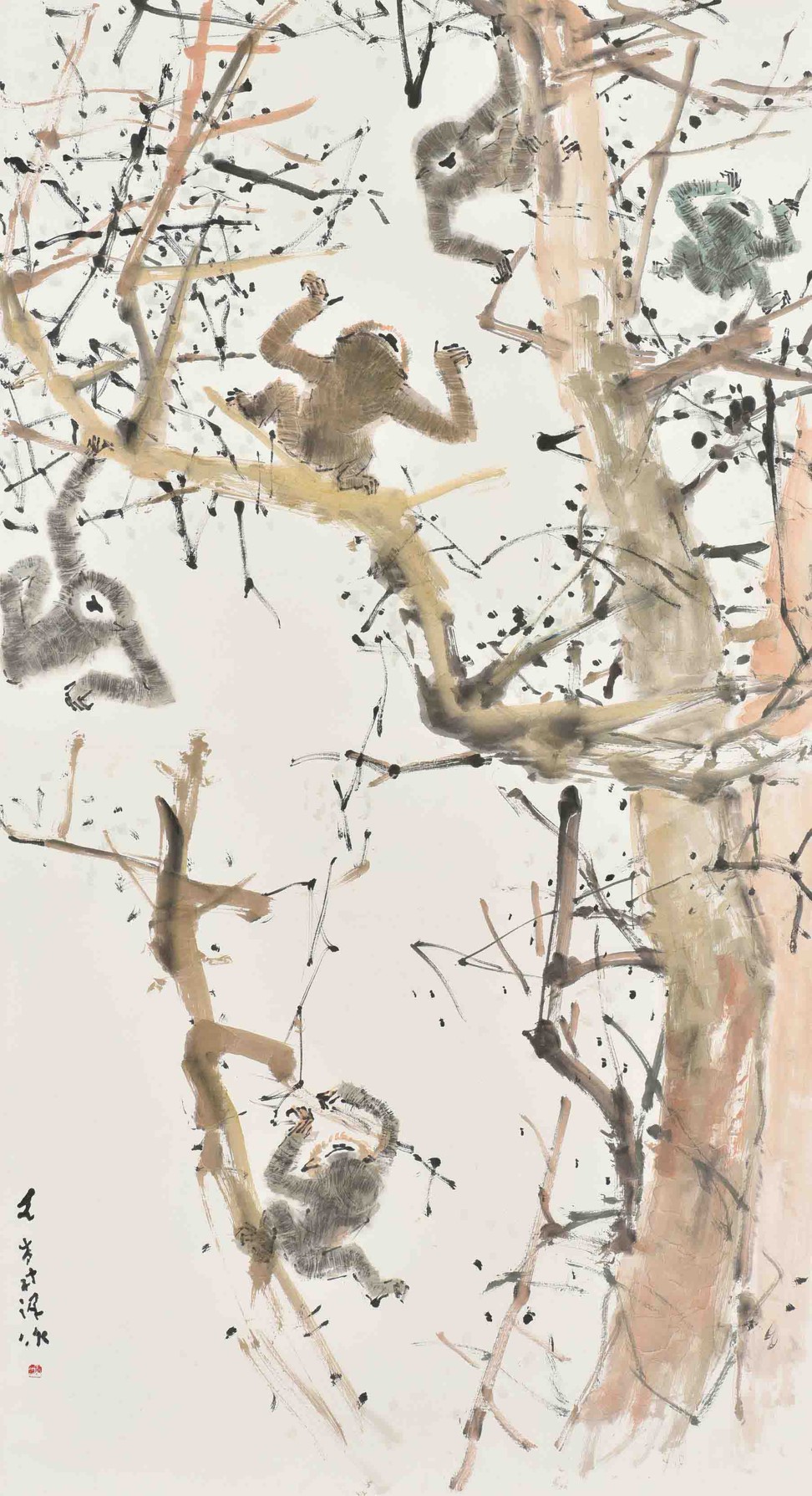

For example, Chen is famous for his paintings of gibbons – one of which is depicted on Singapore’s $50 dollar bill – but standing before one of these works, Quek insists: “Don’t look at the gibbons first. Look at the branches.”

This 1972 painting’s adherence to the aesthetics of traditional Chinese ink painting is clear: the branches are impressionistic if compared to the verisimilitude of Western realism but their textures and details are still deftly articulated. “Then come over here and look at this,” Quek says, striding over to a 1982 gibbon painting, where the branches are depicted more as single strokes: the search for a new purity of form.

“He is progressing, but he doesn’t know where he will go yet.”

Look at his speed of running the stroke. It’s very difficult to create a good, powerful stroke

In a piece painted later still, in 1987, just a few years before Chen passed away, the brushwork for the branches had grown sure and vigorous. “This was the peak,” Quek says. “This style is very different, very complex, and very difficult, but it was successfully done. Here, he’s even given up depicting the details of the gibbons’ fur and faces. But the branches are more important than the gibbons.”

Raffles who? 200 years since the British colonialist, Singapore would rather he disappear

A keen calligrapher himself, Quek says he has sometimes been moved to buy a Chen painting because of one single, beautiful stroke.

“Look at his speed of running the stroke,” he says. “It’s very difficult to create a good, powerful stroke.”

Chen’s interest in fusing East and West stirred long before he came to Singapore. As a student first at the Shanghai Art Academy and then the Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts, he chose a track that allowed him to study both Chinese and Western art. It was difficult, though, to find books about Western art in China then, he once told an interviewer. In 5 Kingsmead Road, he amassed a large collection of these books, and some will be on display in the exhibition.

The artistic explorations of Chen and his emigrant peers in Singapore parallel those of other diaspora communities in the years between the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and the opening up of the country in the late 1970s. Access to new ideas from outside the mainland unleashed a curious flowering of hybrid sensibilities. In Hong Kong, for instance, the artists of the New Ink Movement began to marry traditional Chinese forms to post-war Western art movements to striking effect.

If one considers the likes of the Nanyang and New Ink artists critical precursors to contemporary Chinese artists such as Liu Dan, who toy with and transcend the conventions of traditional forms, a richer picture of Chinese modern and contemporary art emerges.

Indeed, Quek hopes to open a museum in China where he can display his Chen collection, exposing a wider Chinese audience to his work. He explains, simply: “I believe he is a very important figure in Chinese art history.”

Homecoming: Chen Wen Hsi Exhibition @ Kingsmead runs from April 12 to May 3 at 5 Kingsmead Road, noon to 7.30pm daily. Admission is free