‘No place like home’: ethnic Chinese who fled Indonesia for Taiwan remember the deadly 1998 riots that changed their lives

- A deepening economic crisis in Indonesia led to rumours of ethnic Chinese hoarding rice, and resulted in mobs attacking their homes and businesses in May 1998

- Researchers estimate thousands of them fled the country for Singapore, Australia, Hong Kong and elsewhere in the wake of the riots that left more than 1,000 people dead

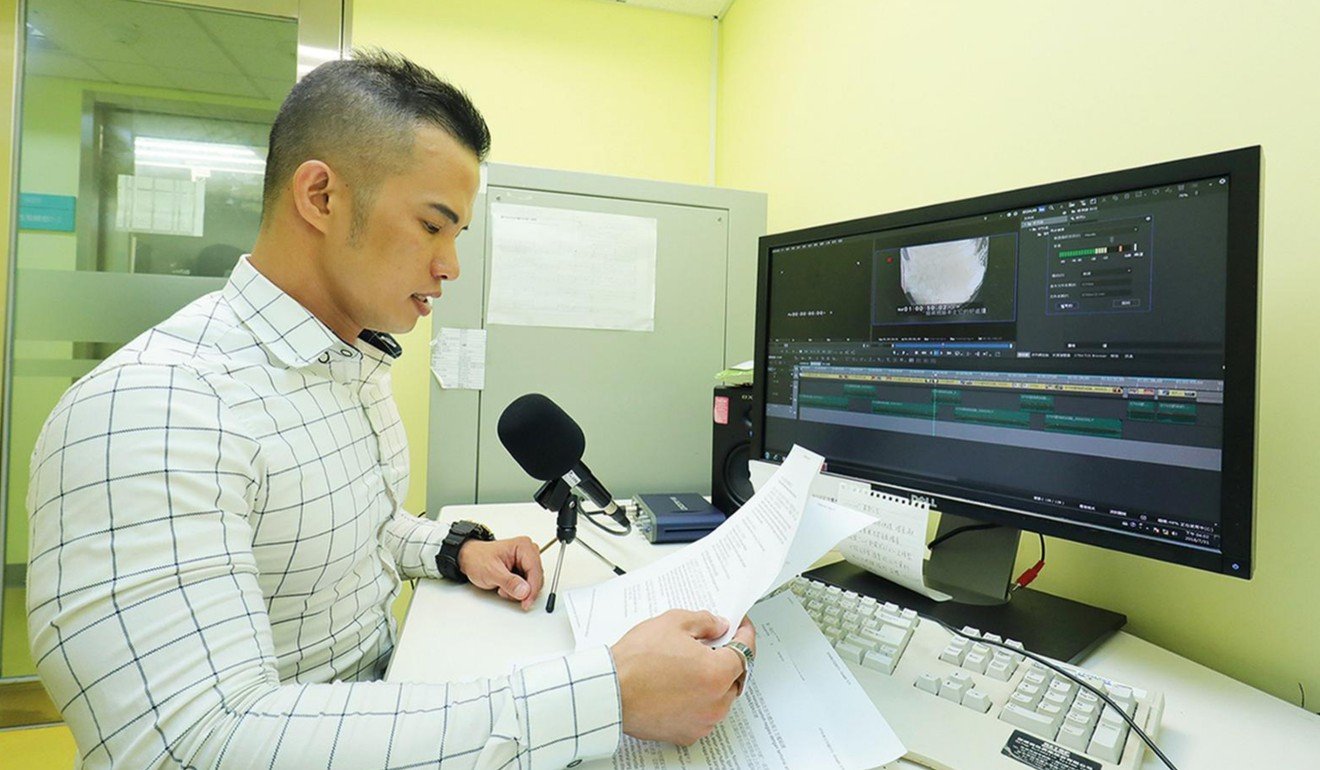

Thamsir, now 42 and a television and radio announcer, remembers a frantic phone call from his mother describing how their family was trying to flee, after a mob burned down a neighbouring house in Jelambar, a sub-district in West Jakarta home to many Chinese residents.

“‘We cannot do anything now, but luckily, there is a river in front of us,’ my mother said,” Thamsir recalls, explaining that residents had blocked the bridge that would have allowed the mob to cross the river and access the house that his mother, father and younger brother were living in.

“Then my younger brother took over the phone and told me to stop talking. He said the family members would take turns to patrol but he would stab anyone who broke in.”

In August 1998, he joined demonstrators on the streets of Taipei to demand the Indonesian government end what he described as a “vile act that had an impact on the Chinese community”.

He knocked on the doors of Indonesia’s representative office in Taiwan and Taiwan’s foreign ministry in Taipei, asking them to put a stop to the pogroms against ethnic Chinese, who made up about 2 per cent of the population.

Rioters attacked homes and businesses owned by ethnic Chinese, provoked by rumours they were hoarding rice during a deepening economic crisis. Human rights groups estimate more than 100 women were raped and more than 1,000 people were killed.

Protests against Suharto continued and several government ministers refused to participate in his cabinet reshuffle. He eventually agreed to resign on May 21, 1998, leaving his deputy BJ Habibie to take over and set Indonesia on the path to democratic reform.

In a September 1998 report, international NGO Human Rights Watch suggested “tens of thousands of ethnic Chinese” fled Indonesia for Singapore, Australia, Hong Kong and elsewhere, fearing a recurrence of violence. Aihwa Ong, an anthropology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in 2003 that 150,000 ethnic Chinese left Indonesia due to the riots.

Two years ago, the Taipei Times quoted Kuomintang (KMT) legislator Apollo Chen’s office saying he heard from a source there were about 1,000 Indonesian-Chinese “who took refuge in Taiwan to avoid anti-Chinese riots and violence”.

Thamsir was among them. When he finally heard from his mother a few days after the first call, it was a bittersweet conversation. The family was safe but their sole source of income, his father’s factory that produced electric cables, had been burned to the ground.

With their finances in tatters, the 21-year-old Thamsir would need to fend for himself, his mother continued. Thamsir took on jobs at a fast-food restaurant and as a part-time radio announcer to support himself while finishing his bachelor’s degree.

But, he says: “I kept wondering, why Indonesia was like that? Why?”

NEVER STOPPED CARING

Thamsir graduated in 2000 and found a job in the Taipei city government. He was a counsellor to then mayor Ma Ying-jeou, and used his Indonesian and Mandarin skills to work on issues affecting Indonesian migrant workers.

He left the job in 2006 and has since run an Indonesian-language magazine for readers in Taiwan, owned a restaurant and invested in various businesses.

He is currently a counsellor at the union of Indonesian migrant workers in Taiwan (IPIT), and is popular within the community, as he also hosts Indonesian-language programmes on Taiwanese television and radio. He has 23,000 fans on Facebook.

There are an estimated 270,000 Indonesians in the country, many of them living in Taipei and working as caretakers and domestic helpers.

Despite his disillusionment with his country, Thamsir still holds an Indonesian passport and plays an active role in Indonesian politics.

He was part of an elections supervisory committee when overseas voting was held in Taipei for the 2009 elections. Two years ago, he organised a flash mob to support former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, an ethnic Chinese, who was seeking re-election.

But Purnama was charged with blasphemy against Islam after a doctored video showed him telling a group of voters not to be fooled by a Koran verse saying Muslims should not vote for non-Muslims. It led to hardliners rallying for his downfall. He was subsequently jailed before being released in January.

Last year, Thamsir became active in Banteng Muda Indonesia, a youth wing of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle led by former president Megawati Sukarnoputri, the daughter of Indonesia’s founding president Sukarno.

He also mobilised support for incumbent Joko Widodo, who is expected to be announced the winner of last month’s presidential election, when official results are released next week.

“I am considered an Indonesian [by the Taiwanese]. I’ve never been seen as Taiwanese or even mainland Chinese [even though I look Chinese],” Thamsir says. “I think this shows how much I care for Indonesia. My concern for my country has never stopped.”

Like Thamsir, Amina Tjandra chose to stay in Taiwan, leaving Indonesia one year after the riots. Originally from Pontianak in West Kalimantan and armed with a degree in economics and management from Atma Jaya University in Yogyakarta, Tjandra says going to the Indonesian capital to look for work was not an option, given the recent violence.

She came to Taiwan to live with her aunt and stayed on in the city of Taoyuan after she married a Taiwanese man. Now 43, she has two sons aged eight and 13, and works as an Indonesian-language radio announcer. She felt safer being among other Chinese people in Taiwan than being in Indonesia, she says.

While Taiwanese people still see her as different “because of my facial features such as my eyes, which are bigger and not as narrow as theirs, and my accent”, it has sparked curiosity rather than dislike.

“Because there’s a difference, they want to know more about Indonesia or the Chinese in Indonesia and anything about Indonesia,” she said.

“It’s because Taiwan’s society can accept differences, live tolerantly. There is an emphasis by the government on multiculturalism and Taiwanese society is now able to accept newcomers.”

MIXED FEELINGS ABOUT HOME

After the May 1998 riots, both Beijing and Taipei raised concerns about the protection of ethnic Chinese with the Indonesian government.

When the countries’ leaders, Jiang Zemin and Habibie, met in November 1998, following protests at the Indonesian embassy in Beijing, Jiang said: “We hold that the proper solution of the issue of the Chinese Indonesians will not only serve … the long-term stability of Indonesia, but also … the smooth development of the relationship of friendly cooperation with neighbouring countries.”

Author Jemma Purdey, in her book Anti-Chinese Violence in Indonesia, published in 2006, said Taiwan was more active and vocal in response to the riots, “demanding that the Indonesian government investigate and try perpetrators and provide protection for victims”.

The Taiwanese government, the book added, threatened to withdraw its investments in Indonesia, which were expected to surpass US$13 billion in the middle of 1998. It also threatened to stop accepting Indonesian migrant workers into Taiwan, of which there were already more than 15,000.

Monika Winarnita, an academic from Australia’s La Trobe University, says the shock of May 1998 still resonates within the community today, especially among the older generation who were already “very assimilated” and felt “they were more Indonesian” than anything else.

She gives the example of Chinese who had intermarried with people from different ethnic groups, adopting Javanese and other cultural practices.

During Suharto’s reign from 1967 to 1998, he forced members of the Chinese community to assimilate by discouraging the teaching of all Chinese dialects, banning Chinese-language media and the celebration of festivals, and instituting a regulation requiring them to take on Indonesian names.

“The May 1998 riots were, therefore, a huge shock to some who gave up all semblance of Chinese identity post-1965, [who] changed their names, and stopped speaking or reading any Chinese,” Winarnita says. “They were supposed to be Indonesian first and foremost yet the events of May 1998 meant that they were differentiated and singled out based on their ethnic features.”

For Tjandra and Thamsir, memories of the riots and of the racial slurs they endured when growing up has resulted in them having mixed feelings towards Indonesia.

Tjandra sees herself as an Indonesian in Taiwan and says she might want to return when she is older: “Who knows? So I still hold an Indonesian passport [after living in Taiwan for about 20 years].”

She laments that anti-Chinese sentiment still exists in Indonesia: in the run-up to the recent elections, fake news on social media about increased Chinese investment and an influx of mainland Chinese workers stoked fears among ethnic Chinese that they might be targets of violence and unrest.

“But it seems like there is progress,” Tjandra says. “I think little by little, there could be change that in people’s mindset, they would accept differences.”

Thamsir says he has grounds to dislike Indonesia but in fact, he feels he has never been detached from it, given his work with the Indonesian community in his adopted home.

“I love Indonesia,” he says. “I never thought of hating it, although I have tonnes of reasons to hate it.”