China's ailing economy needs a dose of Thatcherism with Chinese characteristics

Thomas Deng urges Beijing to trim the state and bolster free enterprise, as Thatcher once did

As the world mourned the passing of former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, remembered her belief in small government, free enterprise and monetarism, and her contribution to world prosperity, we should look at what today's China can learn from her legacy.

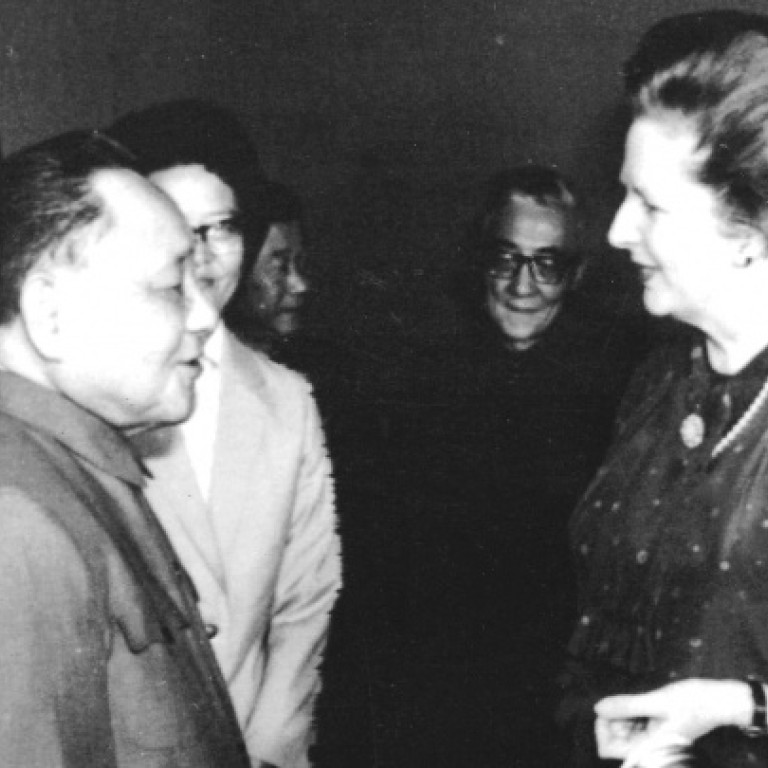

At almost exactly the same time that Thatcher led Britain out of its economic slump, China embarked on its own social and economic reform - with tenets similar to what became known as Thatcherism - under Deng Xiaoping.

Deng understood how the free market functioned, giving people more power over their lives by granting private property ownership, motivating the formation of private enterprises and rolling back omnipresent controls of the government. China has since enjoyed a dramatic ascendance.

But despite its eye-catching growth, China remains a developing country with a per capita gross domestic product that is well below the global average. Its growth momentum has slowed noticeably over the past few years, partly due to a lack of reform breakthrough. Many economic challenges faced by Thatcher in the 1970s pose the same threats to today's China. These include:

First, big government. China's fiscal revenue as a percentage of GDP had increased to 23 per cent at the end of last year from 12.9 per cent in 1992. Its fiscal expenditure as a percentage of GDP has increased to 24 per cent from 13.9 per cent in the same period. These figures are now back to the levels where they were in 1981 when China first embarked on the economic reform programmes.

China's fiscal dynamics diverge from those of the developed markets, where fiscal revenue as a percentage of GDP has dropped a few percentage points over the past three decades since the beginning of the Thatcher-Reagan era to roll back the frontier of the state.

Second, an economy dominated by state-owned enterprises. Similar to Britain in the late 1970s when the government controlled most of the key industries, so the Chinese government today controls PetroChina, China Mobile, Air China and Baosteel, in addition to all the financial giants such as Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.

The 10 largest companies by market cap in China are all state-owned and accounted for the majority share of the total earnings of the stock market last year. The earnings share of private companies remains insignificant after 30 years of privatisation. In developed markets, state-owned firms generally account for a negligible portion of the overall economy.

Third, significant inflationary pressures. Akin to the double-digit inflation rate Britain suffered in 1979, real asset inflation in China has been running at double-digit pace in the past decade, with property prices having skyrocketed. Chinese property is now the least affordable housing market among major economies, and poses a systemic risk to the overall economy.

While the government has imposed numerous rounds of tightening targeting the sector, the asset inflation was made possible by the rapid expansion of credit in recent years.

What have all these policies brought to us? Top college graduates in China, contrary to those in the US who usually fight for jobs in, say, Silicon Valley, compete fiercely to work for government organisations or state-owned enterprises.

The equity markets, which are dominated by monopolistic state-owned enterprises, have been consistently trading at discounts to the developed markets despite China's perceived higher growth potential. Investors' concerns about profitless growth, less robust corporate governance standards, and lack of innovation and sustainable wealth creation may help explain why the Chinese stock markets are only one-half or one-third of their peaks while developed markets like the US, Britain and Germany are trading near or at all-time highs.

All this has undoubtedly impeded China's growth potential, as such factors did in 1970s Britain.

With the new leadership in place, there has been heightened enthusiasm about China's next wave of reforms. Specifically, President Xi Jinping has called for a further opening up of the economy. Xi and Premier Li Keqiang could rekindle reform - which could be described as Thatcherism with Chinese characteristics - as Deng did.

They should privatise the state-owned enterprises and break up monopolies to stimulate job growth in the private sector; trim the bureaucracy and curb runaway government spending; and ensure disciplined monetary policy to stabilise inflation expectations and contain property price appreciation. If Xi and Li can deliver and take the country to the next level, as Thatcher reversed Britain's fortunes, they could be among the greats, as Thatcher and Deng are remembered by the world and Chinese people today.