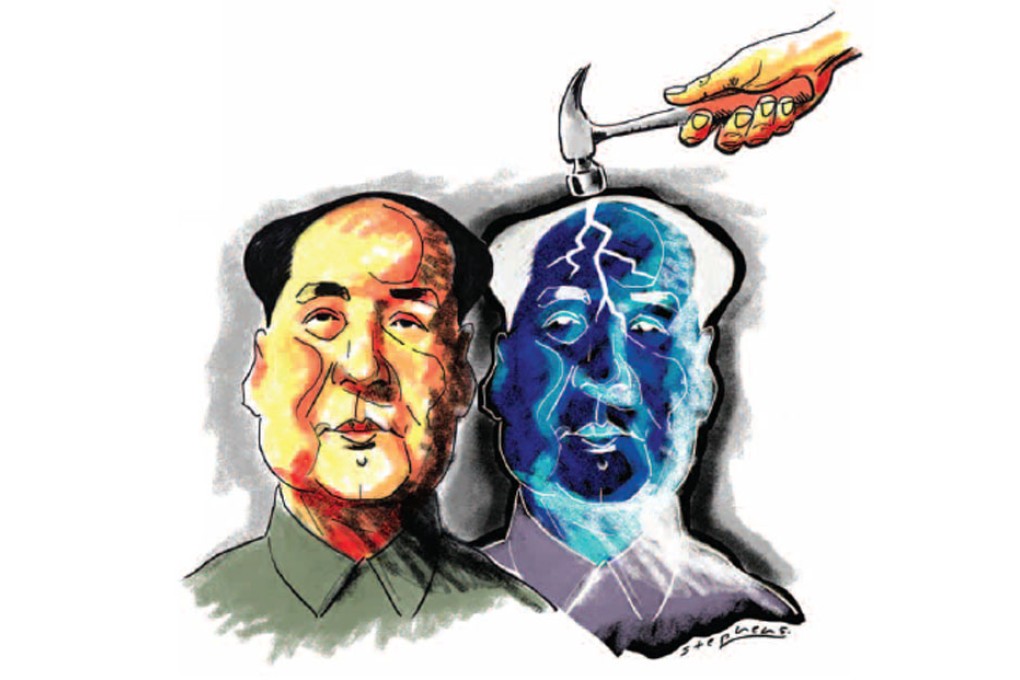

New | Debunking the myths of Mao Zedong

Eric Li says though the Chinese people paid a heavy price for Mao's catastrophic blunders, his leadership set the stage for the country's economic take-off - a fact ignored by many Western critics, while Lijia Zhang believes that the Chinese people's admiration for him should be balanced with a true understanding of his deeds, which isn't possible without open debate

This week, China celebrates the 120th birth date of the founding father of the People's Republic - Mao Zedong. No one looms larger in the narrative of modern China. As the nation continues its ascendency to reclaim its position as a great power, Mao's legacy is central to its perception in the eyes of the world. The ultimate judgment rendered by history remains far into the horizon. But first, some fundamental misconceptions need to be addressed.

The standard narrative in the West is that the first 30 years of the People's Republic under Mao's leadership was an unmitigated disaster and the party-state was only able to save itself by repudiating his ideological rule and taking the country in an opposite direction.

But this is false. Many segregate the party's 64-year leadership into two 30-year periods: the first from 1949 to 1979, mostly under Mao, and the second from 1979 to the present, starting with Deng Xiaoping's dramatic reforms.

No doubt Deng's reforms corrected many previous policy mistakes and delivered enormous successes. But without the foundation built in the first 30 years, the accomplishments of the second 30 years would not have been possible. In the former, the Chinese Communist Party under Mao's helm used its centralised political authority to mobilise limited national resources and built the basic industrial and human infrastructures of a modern nation.

A few statistics demonstrate the significance of that period. In 1949, industrial infrastructure was negligible. Electricity availability outside small urban areas was near zero. Literacy rate was below 20 per cent. Immunisation rate was virtually non-existent and average life expectancy 41 years old.

On the eve of Deng's reforms in 1979, China had built the framework of basic industrial infrastructures, though still very limited. Extensive national and local grids with about 10,000 newly built hydroelectric dams increased electricity coverage to over 60 per cent even in the poorest rural areas. Literacy rate reached an astonishing 66 per cent meaning well over 80 per cent of youth - among the highest among poor developing nations. Hundreds of millions of people were immunised, nearly 100 per cent of children at the age of one, and average life expectancy reached 65. In fact, by 1978, China's human development index was already closing in on much richer developed nations.

A still poor but relatively educated and healthy population with basic infrastructure set the stage for the country's take-off. And all this was achieved with very little resource under an international embargo. Certainly, unmitigated disasters did occur, such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, but to define the entire period as such would be grossly mistaken.