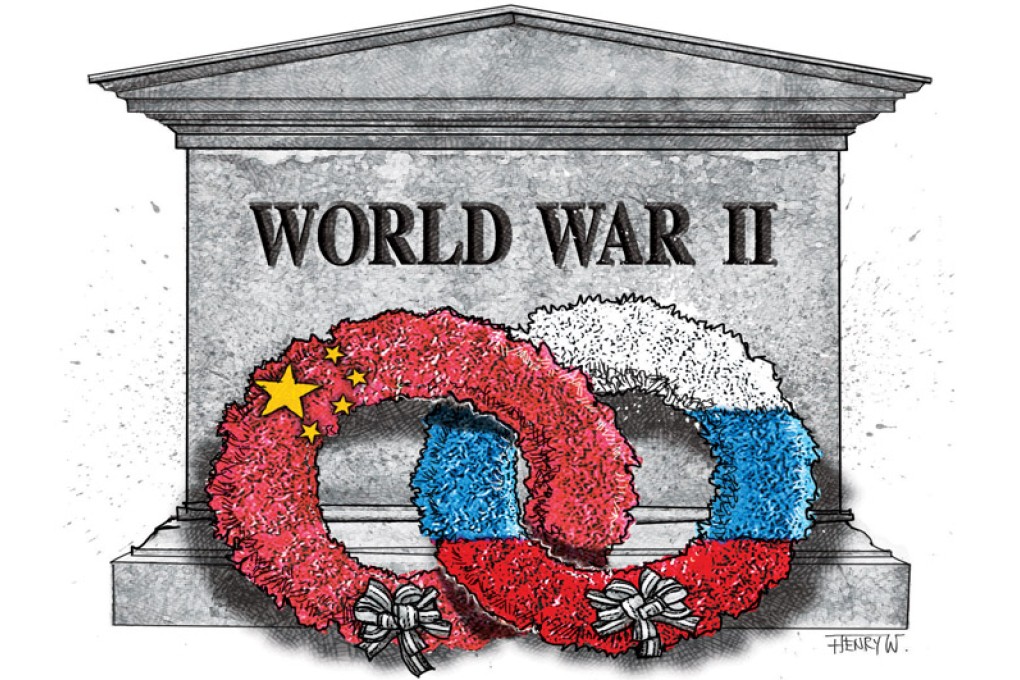

With war commemoration, China and Russia seek a historical narrative distinct from the West's

Paul Letters says China and Russia's decision to jointly commemorate the end of world war two must be understood against the background of their shared experiences - but only up to a point

Last week, China and Russia announced their intention to plan joint commemorations for the 70th anniversary of the end of the second world war. Such cuddling up on the world stage may appear merely a modern political convenience against Western antipathy. The two countries seek to refresh history and commemorate only the sweet taste of a sweet and sour relationship. But when you look at the course the war ran for each of them, theirs was in part a shared experience.

At the hands of fascistic enemies, by 1945, both nations had suffered to an extent many even in occupied Western Europe - let alone more remote America - could only struggle to comprehend.

The number of war deaths (military plus civilian) for the US or Britain were each around 400,000; France, 600,000. We need not six figures but eight for China and the Soviet Union, where most estimates vary between 10 and 20 million and 20 and 30 million respectively.

That experts cannot be sure, within a range of 10 million, how many citizens of China or the Soviet Union were slain says much about the nature of war in those theatres: the dead lay disrespected and unaccounted for on a scale unseen on the western front. It is understandable that at the end of the war, both nations expected to mitigate terrible losses through significant gains from the peace. Soviet forces set a precedent as to how to claim multiple victory prizes, from Prague to Pyongyang. For China, immediate rewards were less abundant; regaining Hong Kong was one dashed hope.

The West has long been blind to the roles China and the USSR played in the second world war. Americans can grow up thinking the Flying Tigers won the war in Asia, yet between 1937 and 1942, the USSR was the only country providing material assistance to the precarious Republic of China's cause. Before the Nationalist withdrawal to China's interior, the vehemently anti-communist Chiang Kai-shek relied upon Soviet air power to enable China to stand up against the Japanese. (Stalin feared losing China to the Japanese more than he feared the Nationalists.)

A few years earlier, the Republic of China had courted military aid not only from the US, but also from the Nazis - until Japan forced Germany to withdraw its military advisers.

The end of the cold war saw the archives open up in the former Soviet republics and, belatedly and tentatively, in the People's Republic. Russia's take on the "Great Patriotic War" crosses communist/non-communist dividing lines, but China is more internally angst-ridden. The Chinese Communist Party has yet to shed its reluctance to illuminate all aspects of the war effort, but, today, Chinese researchers are quietly rediscovering their nation's muddied history, including the enormous contribution the Nationalists made.