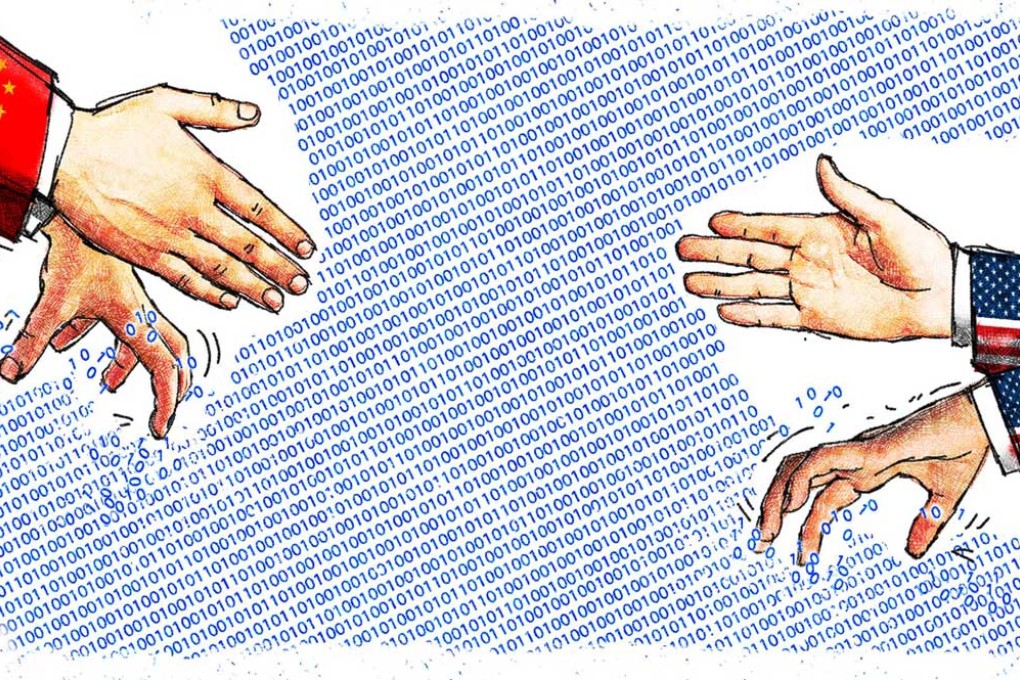

Differing outlooks impede Sino-US cooperation to enhance cybersecurity

Zachary Goldman and Jerome A. Cohen consider the challenge of Sino-US cooperation on cybersecurity

Over the past several years, the United States and China have had conversations – at the highest levels of government – about cybersecurity concerns. These dialogues have focused on possibilities for developing norms to improve relations. Thus far, discussions have yielded little progress. China’s new National Security Law and its draft Cybersecurity Law make clear one reason for the stalemate.

China and the US both talk about “cybersecurity”, but mean different things. In Washington, cybersecurity is fundamentally about preventing unauthorised access to digital systems and, notwithstanding massive foreign hacking of US government databases, mainly focuses on protecting private-sector data as well as critical infrastructure.

In Beijing, cybersecurity is essentially state-centric, safeguarding against digitally enabled threats to the regime, internal and external. China seeks what it calls “cyber-sovereignty”, a term loosely understood to entail significant control over the internet, including over the content of online information.

China’s National Security Law and draft Cybersecurity Law are vague and sweeping, giving the government latitude to take whatever security measures it wishes. Article 75 of the National Security Law, for example, authorises state security organs and military units to “employ necessary means and methods, and relevant departments and regions shall provide support and cooperation within the scope of their duties”. There is nary a limiting principle in sight.

The draft Cybersecurity Law has a similar tone, characterised by broad provisions that permit the government to protect itself more than Chinese citizens. Article 50 authorises the government to restrict internet access in certain regions, enabling it to interfere with the ability of protesters to communicate and organise. Article 31 forces operators of critical information infrastructure to store citizens’ personal data within the mainland. This makes it harder for foreigners to access the data of Chinese citizens, but easier for the government to get it.

Taken together, the new legislation represents a state-centric view of digital security, requiring parties such as network operators to take certain measures and directly empowering the government to take steps vis-à-vis networks or threats.

Despite superficial resemblance of certain Chinese measures to cybersecurity trends in the US, the animating principle in the US is quite different. The American private sector owns most of the infrastructure. It is the target not only of most commercially motivated attacks but, given that US military and government communications traverse private networks, also of those that are motivated by political and military reasons. It is businesses who must actually implement most measures required to improve American security.