Advertisement

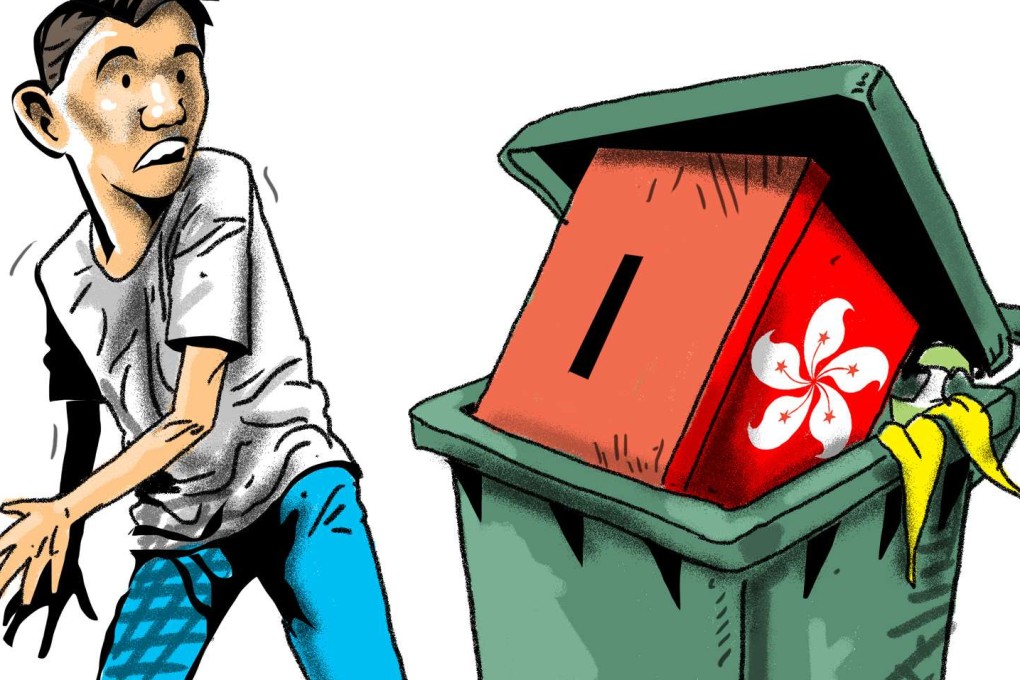

Has Beijing changed its mind about giving Hong Kong people the vote?

Cliff Buddle says 10 years after people were promised a say in electing their leader, we are no closer, despite having endured three chief executives whose governance suffered from having no popular mandate

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Now that the time for that historic election has arrived, Tsang is languishing in prison, convicted by a jury of misconduct in public office. His plans for a democratic election this year lie in tatters. Proposals for universal suffrage were voted down by democrat lawmakers in 2015 in protest at the tight restrictions imposed by the central government on who could stand as a candidate.

We are stuck with an election by 1,194 people, most of whom can be expected to vote for Beijing’s preferred candidate. The result is almost a foregone conclusion. And the candidate likely to win has been careful not to make any commitment to restart the democratic reform process.

Advertisement

All this raises the question of whether Beijing has given up on the idea of universal suffrage for Hong Kong.

In Beijing’s view, winning over the hearts and minds of Hong Kong people is not a priority

The ongoing process for choosing the city’s next leader has, sadly, followed a familiar pattern. It is widely believed that former chief secretary Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor is Beijing’s favoured candidate. There have been numerous reports of lobbying by mainland officials to ensure Election Committee members nominate and vote for her.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x