We trolled an online love scammer to see how far Mr Too Good to be True would go

Women in Hong Kong lost HK$95 million through online romance scams last year; our investigator endures threats and insults from a real scammer to see just what they will do to try to get their money

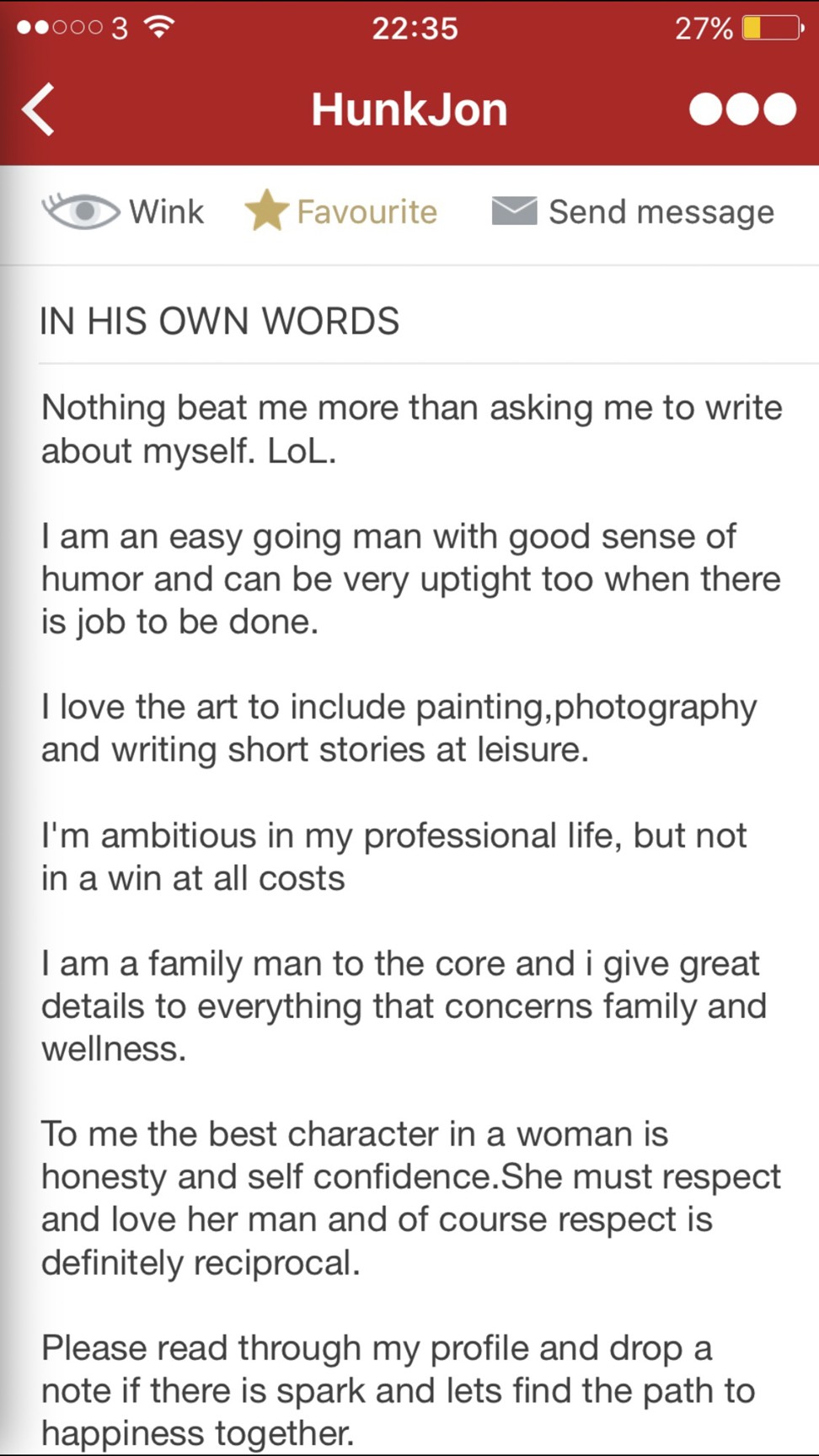

Swedish dentist, PhD, 55, 6’2”, widower, child living with him, a “family man to the core”, seeks a woman, aged 45 to 65, with “honesty and self-confidence, who respects and loves her man” and, of course, “respect is definitely reciprocal”.

You’re a single lady looking for love, so what’s not to like about Dr John – username “HunkJon”. His profile photos and “verified” Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter credentials portray a respectable, clean-cut chap. He’s almost too good to be true. That’s because, in reality, hunky Dr John is a cynical West African romance scammer.

The tall Viking pictured exists somewhere, possibly unaware his image is being used to extort cash from gullible lonely hearts, explains Paul Jackson, a former Hong Kong police officer turned cybercrime investigator.

Despite warnings, English-speaking women in Hong Kong continue to fall prey to online romance scams. In January and February this year, fraudsters netted HK$12 million from 24 female lonely hearts victims, according to the latest figures from the city’s Cyber Security and Technology Crime Bureau (CSTCB). This compares with 114 local cases of internet dating fraud in 2016, with losses of HK$95 million for the whole year.

If you get [the bank account holder] into trouble for nothing I definitely come for you … You playing a dangerous game with me

My attempt to “scam the scammer” started with a friend pointing out suspicious guys posting on Lovestruck, a paid-for dating site popular with professionals. Guys posing as widowed engineers or medics with PhDs, children, good photos: they’re the ones, my friend said. Sure enough, Dr John fitted the bill. After brief chats on Lovestruck, he diverted me to WhatsApp – a common ploy, says Senior Police Inspector Dicky Wong Tik-ki of the CSTCB’s cyber security division.

Dr John explained his UK +44 phone code: he had lived in Manchester with his daughter since his British wife died last year. He planned a Hong Kong business trip, supplying dental equipment to China, and would move here soon. Our banal chats dragged on for weeks, and I began to think he was for real. That’s the game, Wong says. “They use their time wisely, to create a relationship of trust.”

Typically, a roomful of guys sit “grooming” victims for months, Jackson explains. Then they strike. And so it was a few months after meeting Dr John that he wrote: “We need to talk.” He was “having some terrible issues” in Iran on business.

These sites claim they do all the checks … They make it look all slick and polished and protected, but it’s not.

His online banking wouldn’t work and he needed to pay suppliers immediately for equipment already delivered. “I was thinking to introduce you to my bank, so you could do the payment from my account.” It was urgent.

He told me to contact his bank, Lazard, so I could access his account to do the transfer. Pointing out that his bank didn’t know me got short shrift. “Listen, I don’t have time for these unnecessary questions. Contact my bank because they want to meet my girlfriend who I am asking to do a transfer on my behalf.”

Lazard, Jackson observes, ceased operating as a commercial bank in 1933, but that didn’t stop Dr John’s branch emailing impressive paperwork, which bore a striking resemblance to Lloyd’s Bank literature.

His banker requested “government issued identification” and Dr John was impatient: “Why so slow and reluctant?” So I emailed a doctored passport and access was granted to his account, which seemed to have several million pounds sterling in it.

I logged off again without trying to make any transaction, and let two weeks pass, but my slow progress drove Dr John mad. “One would think this was clear enough for a school leaver to understand.” Jackson says my delaying tactics would be wrecking his targets.

I pretended to sign in to his account and sent him a mocked-up failed log-in slip, saying “wrong password”. He gave me another. I pretended to try again, this time sending him a fake failed transaction slip, demanding “non-resident tax certification”. Now panicking, he tried to WhatsApp call me. I ignored him.

Hong Kong woman scammed out of HK$1.4 million by Nigerian ‘lover’

He explained this hitch by saying it was offshore banking, so a “security deposit” of £4,200 (HK$42,400) was needed to release the funds. Could I supply this? “Would pay you right back.” So here, finally, was the sting. I was instructed to wire the sum to Dr John’s UK “tax agent”, a named woman with a London bank account.

This would be a money mule, Jackson explains. Scammers accumulate accounts around the globe; it’s how they get money out. They’re recruited by ads you see in your spam bin, saying “work from home and earn HK$5,000”.

Typically, this mule then transfers the money by Western Union to another mule in the receiving country, who delivers the cash to the scammers. The mules’ cut averages 10 per cent.

By the way I am not a scammer … You have spoken to me, you know I am too smart to come that low

I threw a fake jealous fit, refusing to send money to a woman who was probably his girlfriend. I would only send it to him personally. He got angry. “What can’t you understand? Sending the money to me doesn’t solve any problem … Money should be sent to where it’s useful.”

I was to tell my bank it was a personal transaction. They would ask no questions if I showed confidence, because I was British and bound to send money home. “Baby, listen, this is not an issue.” He emailed a formal loan agreement, promising to repay me within two days. He would see me in Hong Kong soon.

He was alternately rude, charming, then anxious, pushing for confirmation of the UK telegraphic transfer. “Hi what’s the delay, update? You are making this very difficult. You’re stubborn. Like you that way. If you can’t help say so. I don’t need this drama and suspense.”

I decided it was time to hear his voice, so I recorded a WhatsApp call from him. When Wong heard Dr John’s voice, he laughed: “Swedish? Nigerian, I’d say. Definitely West African.”

Saint Valentine’s Day massacre: Australia, Malaysia, Singapore on love scam alert

I pretended my bank queried the UK transfer, asking about my relationship with the recipient. Being a truthful person, I had said I didn’t know her; I was doing it for a friend. It was rejected as a “suspicious transaction”. Dr John was livid. “This is ignorant. You should be better than this. This help is coming at way too high a price ... You’re very dumb.”

A strained apology followed. “Sorry for calling you dumb. But I am really not impressed at the way you have handled this. Below expectations.”

He had another idea. Perhaps it was easier for me to deposit the cash into a local Hong Kong bank account. It was in a female Chinese name, probably a mule or another scam victim.

Then the threats started. “Don’t go to the bank to give that honest explanation. I will be very angry with you.” He now wanted HK$45,000, the extra to pay the “agent fee”. I pretended to make a cash transfer, to avoid paperwork. He demanded the transaction slip. I said I had not taken it – no need with cash. He was fuming. “Every adult knows you need a deposit slip. Who sends HK$45k without proof? You must be very dumb. You will go back there to get the slip.”

When I claimed the police had called, asking about a suspicious transaction, the threats mounted. “If you get [the Hong Kong bank account holder] into trouble for nothing I [will] definitely come for you. What did the police say? You playing a dangerous game with me.” He was panicking now, faced with losing a valuable Hong Kong mule account, Jackson explains.

I told him to stop threatening me. I’d told the police nothing, but they warned me about online scammers. He changed his tune. “By the way I am not a scammer … You have spoken to me, you know I am too smart to come that low.” Then he went sugary, promising to see me, so long as the money showed up in his account by Monday. After that I blocked him.

University’s new smartphone app allows Hongkongers to screen out scammers

It had been a horrible experience and easy to imagine how a vulnerable person might have been frightened and coerced into sending money. Mine was a typical romance scan, Wong and Jackson confirmed.

When contacted, Lovestruck said Dr John had passed their checks with his Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn accounts. Lovestruck said they reported his fake profiles, but at the time of writing, he remained there, big and bold, on Facebook.

Despite pointing out to Lovestruck the numerous suspicious “widower” profiles, they continue to pop up. Jackson isn’t surprised. “They’re running a business too. These sites claim they do all the checks, but the reality is they have few staff and operate with impunity. They’re unregulated and who are you going to complain to? This is a global thing. They make it look all slick and polished and protected, but it’s not.”

Editor’s note: Helen Burgess is a pseudonym