What does the future hold for Asia Society Hong Kong, under pressure from zero venue rental revenue and local political divides?

- Chairman Ronnie Chan and executive director Alice Mong talk about the past, present and future of the society as it reaches its 30th anniversary

- Because of Covid-19 and cancellations due to last year’s social unrest, there has had to be a lot of belt-tightening

Thirty years ago, two internationally minded tycoons opened a Hong Kong branch of the Asia Society, a purely New York-based institution at the time, just when official dialogue between the West and China had ceased following Beijing’s bloody crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

The mission of the original Asia Society, founded in 1956 by a scion of the Rockefeller family, was to educate Americans about Asia. The Hong Kong centre’s mission was quite different.

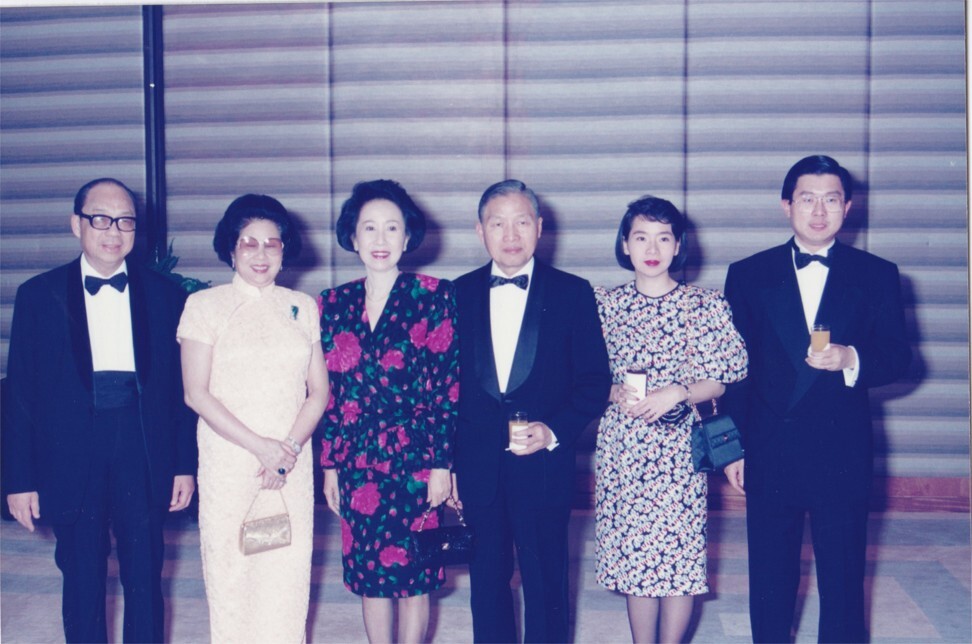

Late Hang Seng Bank chairman Sir Lee Quo-wei and textile tycoon Jack Tang Chi-chien – a relative of politician Henry Tang Ying-yen – wanted to build a bridge between the East and West, a relatively neutral platform where different views could be aired and discussed. It would also become a place where Asians could find out more about their fellow Asians.

Asia Society Hong Kong was created entirely with local funding, helping it stave off accusations it was a US agency. Its first executive director might have been a former US consul-general, but the centre never followed any one country’s agenda, long-time chairman Ronnie Chan Chi-chung says.

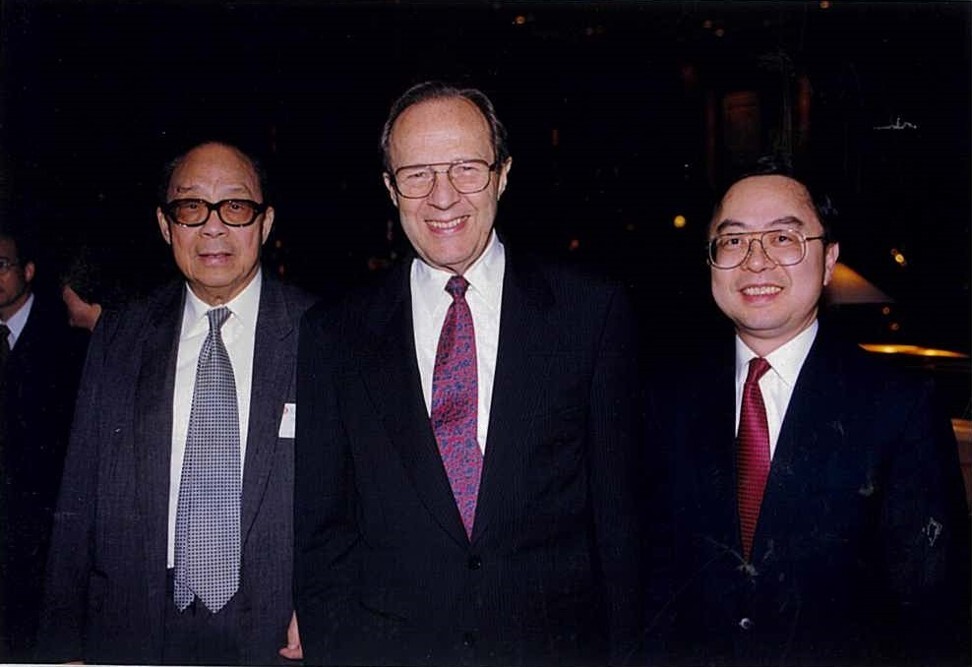

“From day one, the society has never taken sides. It was like that when Sir Quo-wei was chairman before me. It was like that when Burton Levin, the former ambassador to Burma and [consul-general to] Hong Kong, was executive director. We also never take positions on local politics,” he says to the Post.

The 71-year-old billionaire chairman of Hang Lung Properties has always taken pride in having a formidable network in both China and the US, but this is a time of great schisms in Hong Kong. Powerful, competing forces have seen the middle ground eviscerated and institutions of all kinds are boxed into one camp or the other, at least in terms of public perceptions.

The image of Asia Society Hong Kong is inevitably bound to that of its main backers. These are the “community leaders” who will be honoured for their early support at the annual fundraising gala, on November 17 this year, including Sir Quo-wei, Tang and Tung Chee-hwa, the former Hong Kong chief executive who, as the current vice-chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, is on the pro-establishment side of the city’s political divide.

Then there’s Chan himself, the businessman with US citizenship who to many people is the heart and soul of the society because of his long stint as chairman – 26 years since he took over from Sir Quo-wei in 1994.

“Some people criticise us for not inviting so and so. And I say we never invite pro-government people, officials or DAB guys either,” Chan says, referring to the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, the city’s main pro-Beijing political party.

“There is nothing to gain as a platform for local politicians,” Mong says.

The society’s avoidance of government officials differs from the practice at the New York centre, which last month hosted a policy address by President Donald Trump’s assistant secretary for East Asian and Pacific affairs titled “Covert, Coercive and Corrupt: Countering Chinese Communist Party Malign Influence in Free Societies”.

Mong says the Hong Kong centre’s strength is in “shedding light, not heat”. This is one of the mottoes of the Asia Society’s departing president, Josette Sheeran, who will be replaced by former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd, she says.

The Hong Kong centre can do much to add to the diversity of public programmes in Hong Kong, both Mong and Chan say. For example, in April the society launched a series of mostly free online talks on Covid-19, with noteworthy speakers including Nobel chemistry laureate Michael Levitt and Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who co-discovered the Ebola virus in 1976 and caught Covid-19 in the middle of March before speaking to the Asia Society in May.

It was talks similar to these that helped Mong, a young executive sent to Hong Kong by the Ohio state trade office, settle in the city in the 1990s.

“I was in my early 30s. I was from Ohio and the Asia Society had really interesting programmes in the evenings. A lot of them were held at Burton and Lily’s home at Eva Court,” she recalls, referring to Lily Lee, Levin’s Taiwanese wife. “There was always good food too because Lily is a great cook.”

One of the talks Mong attended (and where she first met Chan) was by Andrew Nathan, co-editor and translator of The Tiananmen Papers, a compilation of Chinese classified documents related to the 1989 crackdown.

Mong joined the Hong Kong centre as its executive director in 2012, when it moved from a small office into the 65,000-square-foot (6,400-square-metre) restored former Victoria Barracks in Admiralty. The large physical site enabled the centre to expand its programme from a business and policies focus to one dominated by cultural events, Chan says.

“When our centre opened, we realised the sky’s the limit for arts and culture events, and now we are 70 per cent arts and culture,” he says. Notable exhibitions since 2012 include one of the Dead Sea Scrolls; Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus (1605-6), which was shown with works by local artists inspired by Baroque techniques; and more recently, major retrospectives of two female artists, Pan Yuliang and Irene Chou.

All this relies on the generosity of patrons, Mong says. It took years to raise HK$385 million (US$50 million) to help build the centre, and naming rights were granted for main sections to attract deep-pocketed donors. That was how the large Joseph Lau and Josephine Lau Roof Garden got its title, named after businessman Joseph Lau Luen-hung and his daughter. Two months after the centre’s opening, Lau was accused of bribing former Macau government official Ao Man-long in a high profile trial, and he was convicted in 2014.

As a Chinese-American, my loyalty is going to be questioned. But I am excited about the next 30 years of the centre. In the end, it’s all about showing loyalty to our missions

The naming right was an agreement and the Asia Society cannot take the name away, Mong says. Chan adds: “We had to go out and hustle for money to build the Hong Kong centre. Who the hell was going to give us money? So we offered naming rights. In fact, with that particular case I was very careful. I brought it to the board and the board approved it. Later, that gentleman got into some controversy, shall we say. There is nothing we can do, just like every university that receives money from donors. You always have that risk. Anyway, it is only one case among our donors. One out of 10, it’s not bad.”

Other donors with names prominently displayed around the centre include the Riady family, who are behind the Lippo Amphitheatre, named after the family’s Lippo Group; and the wife of Robert W. Miller, founder of Duty Free Shoppers, after whom the art gallery is named following Miller’s HK$100 million donation in 2014.

This gives the impression that the Hong Kong centre is flush with cash, which it is not, Mong says. The bulk of the running costs is normally covered by venue rentals. Because of Covid-19 and cancellations due to last year’s social unrest, there has had to be a lot of belt-tightening, she says.

Former employees at the society’s gallery and exhibition division have also said that its image as a “rich man’s club” has always made it hard to raise funds for exhibitions, which rely on outside donations since there is no funding ring-fenced for such activities.

Chan says he is trying ways to keep the centre sustainable, and then he will step down as chairman. “I have wanted to get out since 1999, but I have to leave it in a good condition, including financially. And today, financially we are still struggling,” he says.

Mong, meanwhile, is not fazed by the politics or the financial challenges. “As a Chinese-American, my loyalty is going to be questioned,” she says. “But I am excited about the next 30 years of the centre. In the end, it’s all about showing loyalty to our missions. Our founders wanted to build a bridge. That mission has become more important than ever.”