‘I thought about Bruce Lee’: how Hong Kong artists in Britain struggled to feel from afar the pulse of their home city, and to represent it

- A dance trio often invoke Hong Kong’s identity as a central theme of their art; their latest work combines cart noodles and game shows they watched growing up

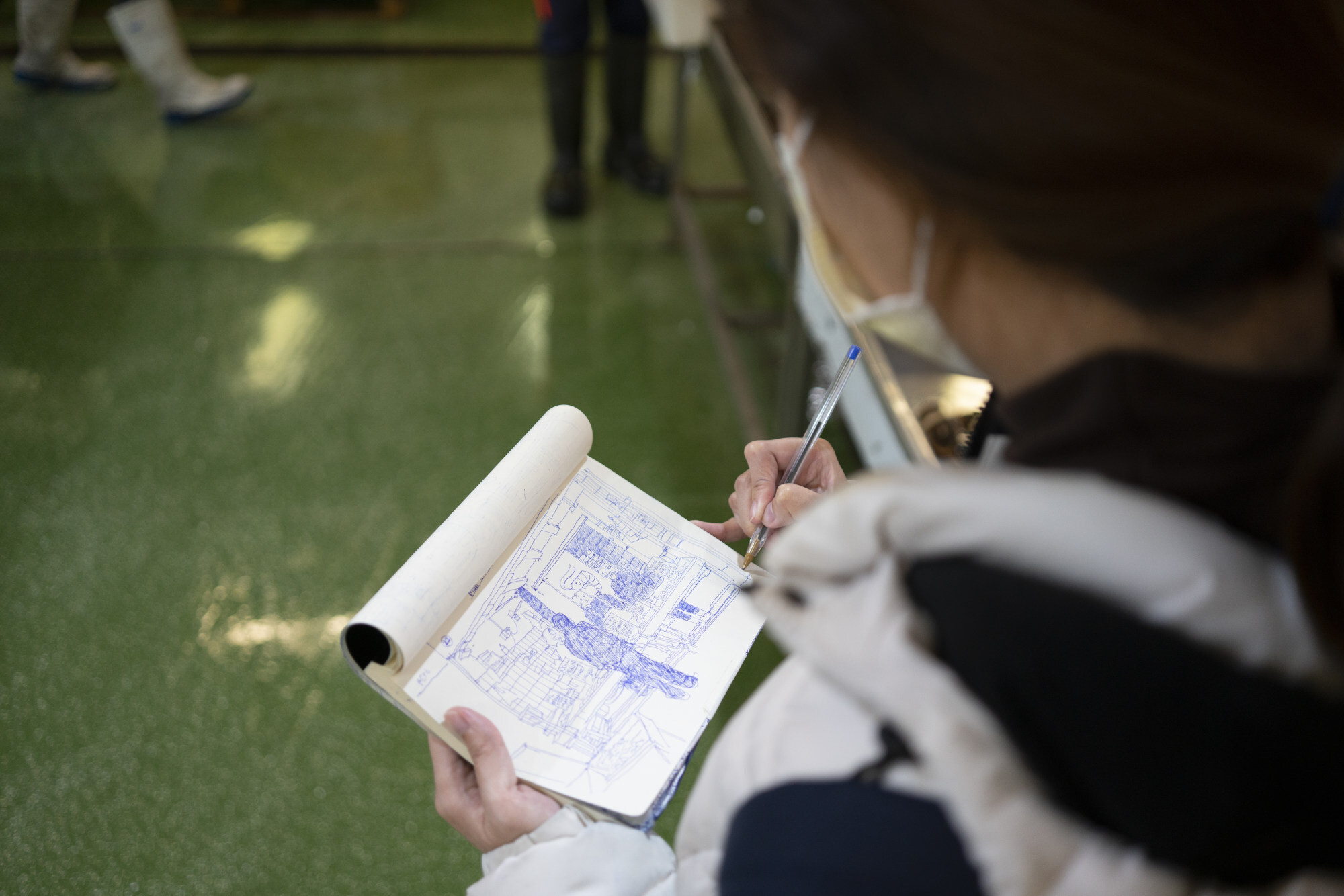

- An illustrator who sketched Hong Kong scenes to preserve collective memories continued the practice when she moved to London, drawing fish market stallholders

After a year studying dance in Britain, contemporary dance trio ShumGhostJohn flew back to Hong Kong when in-person classes were suspended because of the Covid-19 outbreak in early 2020.

The next six months in Hong Kong gave them a chance to feel the pulse of an arts scene they had never truly known – and they discovered it had not escaped the political upheaval that had gripped the city for months.

The three dancers – John Chan, 30-year-old Ghost Chan Hon-kit, and Shum Pui-yung, 25 – are among a number of Hong Kong-born artists who have found success in the British arts scene in recent years. This is despite the barriers historically experienced by East Asian artists and many instances of discrimination. Still, although they now work abroad, they try to stay connected with their home city.

After they enrolled in a graduate programme at the London Contemporary Dance School in late 2018, the trio kept up with news in Hong Kong through conversations with friends and family, as well as social media.

But this observing from afar was like looking at the city through a fragmented, “telescopic lens”, says John Chan. “There was this thing that was lacking. It was just impossible to have an accurate grasp of the texture of the city.”

‘No one stood up for us’: Asians in Europe wake up to truth of racism

As a group that emphasises the physical and tangible in their work, and frequently invokes Hong Kong’s identity as a central theme, gaining their own sense of this new “texture” was critical, say the members of ShumGhostJohn.

This texture is key to their latest project, the Cart Noodle Show, an interactive, storytelling game show.

It is also modelled on old television game shows they remember watching as children, which “had this really absurd, Hong Kong-style humour that makes up part of our identity”, says John Chan.

He adds: “Cart Noodle Show is an interactive game show that uses childhood memories of Hong Kong pop culture and street food to explore ShumGhostJohn’s thoughts and love toward Hong Kong.”

The trio returned to Britain in autumn 2020 and performed the first Cart Noodle Show online in February at the Dare Festival 2021, an annual three-day interactive theatre festival hosted by London’s Shoreditch Town Hall and Upstart Theatre.

“I felt bad that I could not be there with the people. The only thing I could do is watch the news and draw illustrations,” Wong recalls. She had to find her own way of fighting for her home, she says, and laughs as she explains her source of inspiration.

“I thought about Bruce Lee, how he as a Hongkonger sought to build up a very good image and impression of Hong Kong internationally,” she says. “If I am a Hongkonger, how can I do better in my work to represent Hong Kong well to the public? I tried very hard to do this, even in school.”

Preserving communities through artwork has been a passion for Wong since she began drawing urban Hong Kong in 2014, finding herself drawn not to the landscape itself, but to how the community existed within it.

Sketching quickly became what Wong described as her “weapon” to help preserve Hong Kong’s collective memory and identity. She went on to publish two books of her illustrations of the city, entered a number of partnerships, and her work was collected by the Hong Kong Museum of Art.

But after a half-decade of sketching, Wong found herself struggling with her artistic voice and seeking a reset. She enrolled in a graduate programme at London’s Royal College of Art, closed her studio and moved to Britain in 2019.

Wong’s most recent project, the Barter Archive, is a two-year effort to “preserve the collective memory” not of Hong Kong but that of the Billingsgate Fish Market, a wholesale fish market legally established in the City of London in 1699 and relocated to East London’s Canary Wharf in 1982.

Wong initially stumbled on Billingsgate in a BBC documentary. She was attracted to the unique culture of the fishmongers who worked at the market – who had become so infamous in Britain that “Billingsgate” became slang for coarse, vulgar language.

Starting in October 2019, Wong began visiting the market early every morning and engaging with the fishmongers, while sketching what she saw.

“My first impression from the BBC documentary was that they all seem like old, scary strong men, with very strong London accents that would create a language barrier between us,” says Wong.

“But really, once you spend time with them, you find they are very kind and nice. To be honest, if I did the same thing in some market in Hong Kong, I’m not sure it would have been quite as welcoming.”

Wong developed a close relationship with many of the fishmongers – only to find out that Billingsgate was set to be relocated in the coming years because of the area’s rapid economic development.

That is where she came up with the concept of the “barter” archive: rather than trying to replicate the archiving techniques traditionally used by large institutions, she offered to exchange her daily sketches with items lent to her by the fishmongers.

These could be anything they felt captured the spirit of Billingsgate – their favourite coat or pair of boots, a licence to work at the market they had renewed for decades – but the decision was up to them.

After the exchange, Wong recorded an interview with the fishmonger, and the item was digitally scanned before being returned. The scans, interviews, and sketches were then all posted on Barter Archive’s website.

Wong recalls one particularly powerful moment, when she tried to exchange for a little lobster pin one fishmonger had worn on his jacket for 20 years. He was reluctant to let it go, even temporarily. “It is his treasure, it was so important that he had to consider whether he would lend it to me,” says Wong. “This kind of value, you cannot judge based on money.” The project is not just meant to capture these memories, she continued, but also to provoke reflection and debate among the public about the costs and benefits of economic development.

Wong’s method of open, transparent negotiation with the Billingsgate fishmongers was critical to breaking down the barriers that Asian artists frequently face in Britain, says Sandra Lam Wan-yi, a London-based curator and writer who is curating the Barter Archive.

“It is really difficult to have Asian voices heard in the UK art scene, with Asian and Hong Kong artists under-represented across the art industry here,” Lam adds. “This is how we can get our voices out, and this project also helped bring more diversity to the community.”

Wong and Lam now want to collaborate with local museums to host exhibitions for the Barter Archive and work directly with other archives. “We want to make it a living archive, to find out how it can continue to exist even after Billingsgate is relocated,” says Wong.

They recall people in their neighbourhood clearing the way for them as they walked past, being called “corona” countless times, and even one physical altercation on London’s Underground railway system.

Ghost Chan remembers how his brain froze the first time someone came at them. “It happened so quick,” he says. “It was the first time being called ‘corona’ and it didn’t even register in our brains.”

But the three dancers also recall a happier moment, when they managed to attract enough interest from the local Asian community to half-fill an auditorium for one of their shows.

ShumGhostJohn plan to continue developing the messages behind their works, and hopes to perform in both London and Hong Kong regularly.

“One of the values we are currently working on is how to connect the community, because during this pandemic all of us have kind of been separated,” says Shum. “How can art bring, and connect, people together? How can it link memories and social values together? Exploring this will be our next step.”