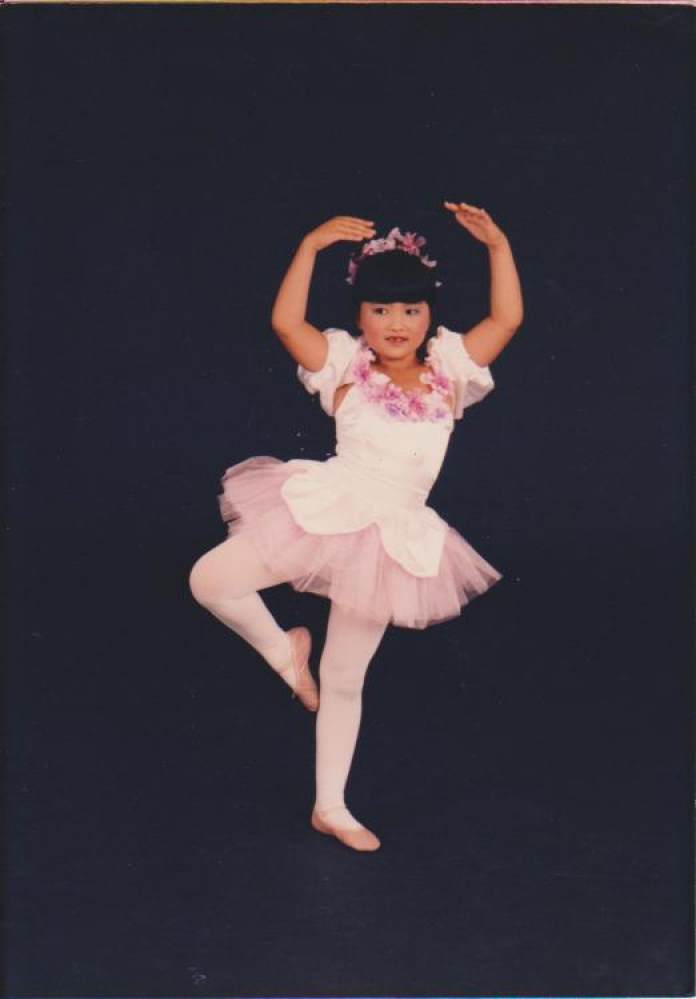

Asian-American dancer Marisa Hamamoto, who founded dance company for disabled and able-bodied, talks about her pain and why she’s dismantling stereotypes

- When she was 19, Marisa Hamamoto was sexually assaulted. Not long after that, she suffered a stroke, triggering ‘years of trauma’ for the dancer

- Her determination to overcome both these events have resulted in her setting up a dance company open to anyone who wants to take part, able-bodied or disabled

Marisa Hamamoto wants to make sure that anyone, regardless of physical ability, feels like they can join a dance class or take part in discussions about race, gender and diversity.

Hamamoto knows she has a long way to go to accomplish these goals – but the Japanese-American (earlier this year named one of People magazine’s Women Changing the World) is not one to shy away from a challenge.

Hamamoto’s father was a third-generation Japanese-American from Hawaii. He met and married her Japanese mother, who gave birth to Hamamoto near Nagoya in Japan. When she was two, the family moved to California.

Hamamoto’s sense of inadequacy, of “not being enough”, was especially pronounced when she was sexually assaulted by a dance teacher. “I was violated, and my body felt like it didn’t belong in this world,” she says. “There was a deep-rooted pain everywhere.”

In 2006, she suffered a stroke that left her paralysed from the neck down – yet after two months in hospital, she was able to walk out on her own.

“I don’t know how I recovered,” she says. “But it allowed me to develop a strong sense of faith. Within the pain and struggle, I kept believing in the journey – that I am destined to be a dancer, and I am born to dance. A higher power was telling me that I was going to be doing something bigger and broader with dance.”

After some research, Hamamoto discovered that one in four people have a disability in the US, but that opportunities for dancing in the disabled community were few and far between.

In 2015, she created Infinite Flow, a professional dance company open to people of all abilities and ages. The dancers perform at private events, schools and corporate retreats. The performances are moving, celebratory and triumphant, exemplifying how wheelchair users are as graceful, spirited and precise as anyone else.

“For us, it became a way to use dance as a catalyst to promote inclusion,” she says. “The commentary I was getting was, ‘Marisa, the stroke survivor who temporarily couldn’t walk, is now teaching dance’. But for me, it was destiny.”

She made a film, Scoops of Inclusion, featuring multiracial dancers who encounter a paraplegic gym teacher, a blind school newspaper editor and a deaf music teacher.

“It’s available to schools, families, anyone who wants to watch it,” says Hamamoto. “If there’s one thing I’m really proud of, it’s this film.”

“My dance company is ultra diverse, and I wanted to take the same approach here. So it asks the question: ‘What do you think when you hear the word ‘disability?’. By July next year, I hope for 31 million junior school children in the US to have seen it.”

Many parents, she says, do not want to expose their kids to the idea of disability.

“I’m super optimistic, and I tend to think everyone is just going to get it,” she says. “Society likes to put the pity story on disabled people. With Infinite Flow, I want to bring awareness so people can be proud of their own uniqueness, where we’re not just checking off boxes but looking at their stories and identities.

“I’m here to dismantle the boxes people try and put you in. Everyone should be valued for who they are.”