Novelist, 1920s Hollywood screenwriter, half Chinese: why Winnifred Eaton gave herself a Japanese name, Onoto Watanna

- Little is known about Chinese-Canadian writer Winnifred Eaton Babcock Reeve, who is said to have been the first novelist of Asian descent in North America

- Early on in her career, she pretended to be Japanese to sell stories. In the 1920s she was a Hollywood screenwriter, and later wrote some harshly realist novels

Winnifred Eaton Babcock Reeve’s story is nothing short of remarkable.

From July 27 to 29, around 40 academics from around the world, including Japan and Hong Kong, will descend on Calgary, Alberta to discuss the extraordinary life of Winnifred Eaton – known to her readers as Onoto Watanna and in Hollywood as Winnifred Reeve.

Despite there being an extensive archive of her work, memoirs, interviews and biographies, not many Canadians and Americans know about Eaton, which is why those in charge of the coming conference plan to shine a spotlight on this creative Chinese-Canadian.

Some of Eaton’s descendants will also attend the three-day conference to learn new things about their forebear who, by the time she died in 1954, had written 18 bestselling novels, 80 stories and more than 60 works of non-fiction and poetry; and written and edited 50 film scripts.

First-time novelist on reimagining Chinese myth and reaching for a dream

“As a literary scholar, I’m always looking for some kind of core consistency in authors, but Winnifred is a chameleon who reinvented herself many times in the course of her career,” says Mary Chapman, a professor at the University of British Columbia who focuses on American literature and transnational American studies.

“I find that fascinating, even if one phase of her career was deeply problematic.

“She was desperate to survive in a competitive literary marketplace so she catered to its desires as they shifted and changed over time. She started by writing formulaic, sentimental Japanese romances and ended her career with brutally realist fiction about the Canadian west.”

Chapman, who is organising the event, is not only fascinated with Eaton, but also her biracial family, about whom she is currently writing a book.

Her parents, who met in Shanghai, were married in 1863. They moved to England, then bounced between New York and London before finally settling in Montreal, where Eaton – the eighth of 14 children – was born in 1875.

Eaton tried her hand at journalism at the age of 20 but then decided she wanted to be an author. At the time, Japanese art and design was fashionable in the West.

“And then she had this new name, Onoto Watanna, and she started publishing.”

The first story she published was A Japanese Girl in 1896, and Eaton – or rather, Onoto Watanna – became a hit.

“I think the impersonation just ran away with her – she let that genie out of the bag and people were curious, and Madame Butterfly was popular. There was cultural mystique around it, so she wrote a bunch of stories to answer that popular demand,” explains Chapman.

Eaton’s first novel in 1899, at the age of 24, was Miss Nume of Japan. In it, a young Japanese couple are betrothed but the man heads to the US to complete his studies. There, he meets an American dancer and they fall in love, forcing him to choose between his American love or the woman he has promised to marry back in Japan.

Timeless romance between a British officer and a Japanese divorcee

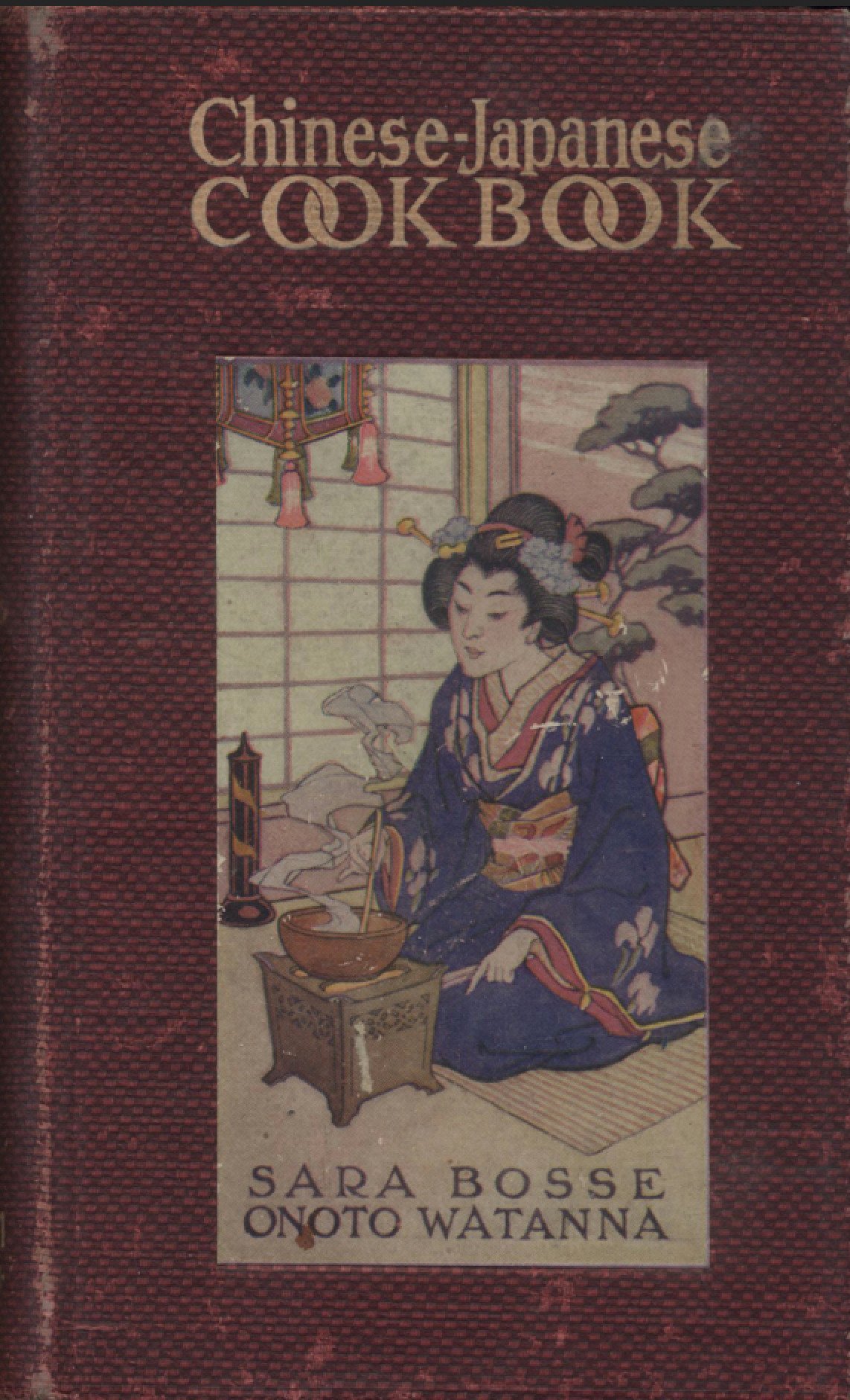

Eaton even collaborated with one of her sisters, Sara Eaton Bosse, on the 1914 Chinese-Japanese Cook Book. Neither had much knowledge of the cuisine or cooking and one of Chapman’s colleagues, who tried to make some of the dishes, proclaimed them “so bad”.

Eaton continued this pseudo-Japanese identity for about 10 years. While Japanese people questioned her ethnicity, her publishers wanted her to keep the charade up, as her stories sold well.

After her marriage to writer-journalist Bertrand Babcock broke down, she wed American businessman Frank Reeve in 1917 – the same year she finalised her divorce from Babcock – and they moved to a ranch in Alberta.

“She was writing screenplays or collaborating. A lot of these don’t get [credited] exactly because they are so collaborative that the last guy who revises [it] gets the credit, and everybody who chipped in earlier might not be acknowledged,” says Chapman.

More study needs to be done to confirm Eaton’s contributions – work which is further complicated by her using different variations of her name.

“Women were seen as knowing how people talk and dress and socialise and behave,” says Chapman. “So they were seen as people who could write the scenes where – if you think of a movie where it’s dinner or tea, and guests are arriving and like a little play – they know how people dress and what they say.”

Eaton explored mixed-race relationships that were considered risqué in her screenplays. This horrified puritanical Christian groups who wanted to clean up the big screen.

“She was writing stories that dealt with topics of people having sex, people of different races, and people smoking and dancing,” explains Chapman.

“By the time the screenplays satisfied censors, they were unrecognisable from her perspective. So it was really a career-changing shift. Everybody who worked in early Hollywood noticed by 1930 there was a drop-off in what can be imagined and filmed.”

By that year, Eaton had left Hollywood and returned to Alberta, reconciling with her second husband after discovering he had had an extramarital affair.

Kept from her birthplace by Covid-19, Chinese writer recreates it on the page

Her writing style changed drastically at that point, moving away from titillating romances to harsh realist novels. Chapman says this was a period of some of Eaton’s best work – including Cattle, written exactly a century ago.

“I really think this novel is a kind of cinematic masterpiece for her. And it would be great if more people read it.”

Eaton died of heart failure at the age of 78. Her granddaughter Diana Birchall, who has written a biography of Eaton, has continued in her grandmother’s footsteps in Hollywood.

“Until 10 years ago, at MGM, people would send in scripts and she’d read them and say this looks interesting or not,” Chapman says. “So there are a few other writers in the family, or it seems like [with] the artistry of the various generations, there’s still some writerly, cinematic connection there.”