Does new M+ exhibition based on East Asian ink landscape paintings go too far or not far enough?

- ‘Shanshui: Echoes and Signals’ aims to expand the notion of shanshui – East Asian ink landscape paintings – and bring it to ‘the level of our contemporary world’

- It is in many ways successful in what it sets out to do, but exhibits of electronic items may raise eyebrows, and there is a lack of historical context

“Shanshui: Echoes and Signals”, the new exhibition at Hong Kong’s M+ museum of visual culture in West Kowloon, adopts an all-embracing approach to the genre of East Asian landscape painting that originated in China over a thousand years ago.

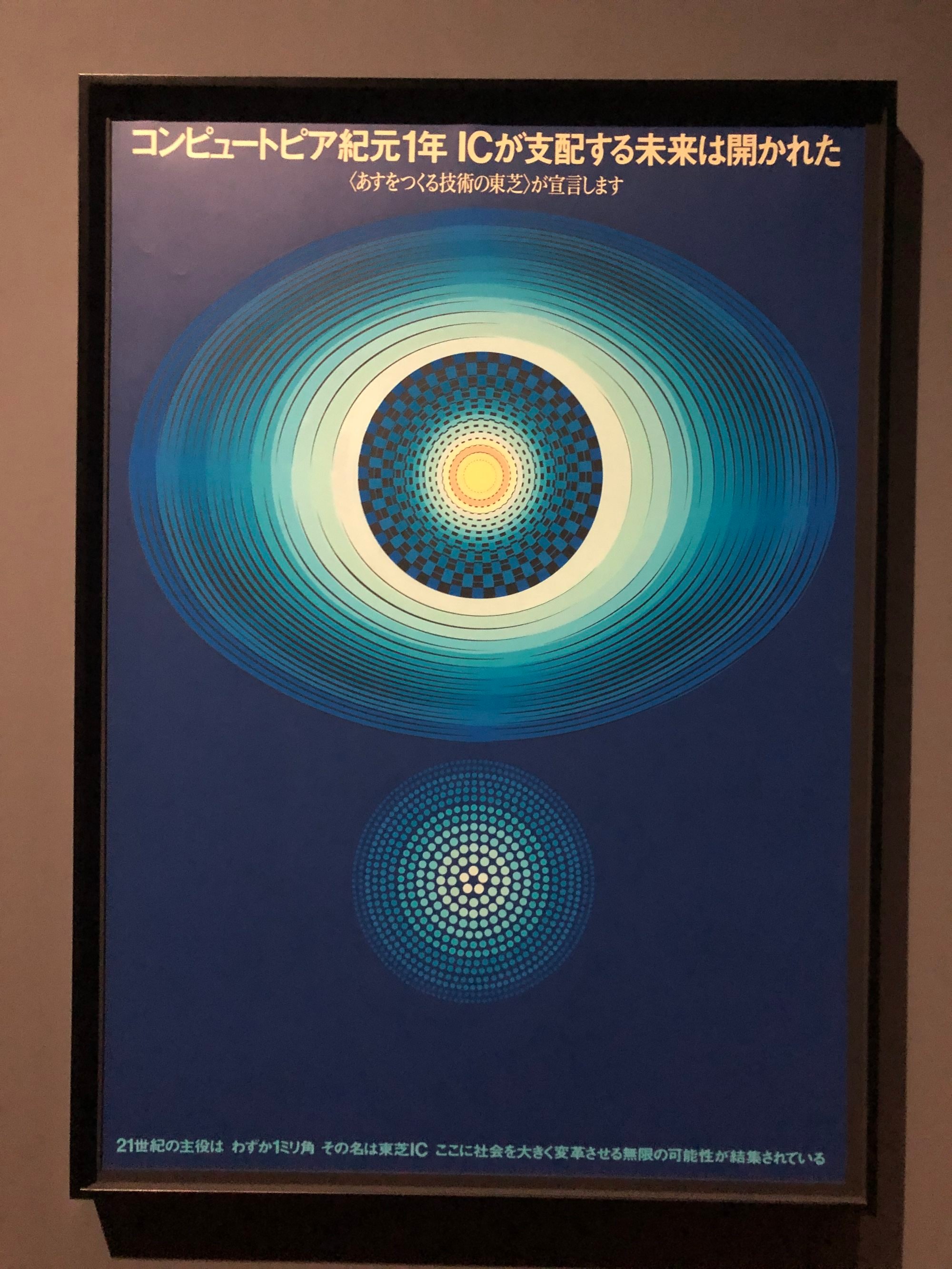

But some might wonder whether it has spread its arms a little too far. As a fellow journalist asked the curators during the press preview: since the exhibits include radios and a mobile phone (the actual physical items), is there anything that couldn’t have been shown here?

To say that a 1989 NTT Docomo TZ-803 – one of those clunky first-generation mobiles we call “Big Brother” phones in Hong Kong – is relevant to a reconsideration of shanshui, which literally means mountain and water in Mandarin, is typical provocation from a museum with a mission to level the silos and flatten hierarchies between different artistic disciplines.

“We really want to bring the show to the level of our contemporary world,” says Silke Schmickl, the Chanel lead curator for moving image at M+.

These amazing clay works will crumble right in front of your eyes

“Extractions from the mountains, the digging for minerals, the shortage of some of these materials, have become very tangible for us. Without the mountains and water and energy, we wouldn’t have any of these [new technologies].

“I think these tools are sort of prompts for us to think that [shanshui] is something that is embedded in our understanding of the world as a whole.”

The curatorial text also links the idea of modern communication with humankind’s perennial desire to connect with higher powers.

“As you discover these devices throughout the exhibition, consider the meaning of landscape in the digital age and the invisible telecommunication networks overlaying our physical world,” it reads.

One may question if using shanshui as an overarching paradigm is akin to replacing domineering Euro-American-centric art historical narratives with an equally overbearing hegemony.

But the curators explain that they are not offering a “doctrine”. While the exhibition includes a work by the late Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta – her 1975 film Silueta Sangrienta (Bloody Silhouette) – and of course the radios and phone, most of the artworks are consciously informed by the ink tradition, they say.

The exhibition is in many ways entirely successful in encouraging new appreciation for the essence of ink landscapes. It also reveals how the genre inspires subversive strategies for all kinds of artists, as well as showcases some beautifully sited installations that draw the eye to the mountains and water surrounding the museum.

The first gallery sets the tone. Shanghai-based Guo Cheng’s newly commissioned Becoming Ripples is a wall of mirrored fabric that shivers and shimmers to its own internal rhythm.

In Yang Jiechang’s Black & White Mustard Seed Garden (2009-2014), the Chinese ink artist introduces scenes of bestiality and predatory violence to challenge the cultural authority of a classical art form.

Hong Kong-born Wesley Tongson’s Spiritual Mountains 3 (2010) was made entirely with his fingers and other parts of his hands. Xu Bing’s sketches of the Himalayas are composed of words in Chinese and English representing elements of a landscape painting.

Singaporean artist Chua Chye Teck combines a collection of miniature scholar’s rocks with construction debris. (In another room, Hong Kong artist Leelee Chan’s Endless Consumption is another example of a sculptural landscape made with found, discarded materials.)

There is also the first of American artist Isamu Noguchi’s steel, abstract mountains that appear in the exhibition. Later, in one of the galleries with a view of the sea, a “forest” of his steel landscapes is on show, accompanied by Singaporean composer Vivian Wang’s soundscape that varies according to the light and crowd motion.

Another sunlit room is given over entirely to Korean artist Lee Ufan’s Relatum-The Mirror Road (2021/2024), in which a long strip of polished steel lies between two rocks, surrounded by a bed of pebbles. Visitors can walk all over this work and relish the feeling of being part of a landscape painting come to life.

The duration of the exhibition – it will remain for two years – allows for partial rotations of exhibits. The Lee Ufan, for example, will give way in eight months to works by Roni Horn and MAD Architects, respectively.

It is, on the whole, a slow, or slowing, exhibition. There are a number of “durational” films, where the camera is trained on a rock, for example, or a mountain, with changes occurring at an almost imperceptible pace.

Chanel Kong, curator of moving image at M+, explains that many of the works mirror shanshui paintings in the way that they take a creative approach to scale, contrast the permanence of the land with fleeting human presence, and engage viewers, who complete the work by actively casting their eyes at different parts of a work with multiple perspectives.

One of the most exciting crossovers of shanshui and film in the show is a new work called 47 Days, Sound-less by Vietnamese artist Nguyen Trinh Thi.

For part of the 30-minute, multichannel work, there is no visual, just sound recordings of birds and animals in nature. The images, when they appear, are snippets taken from Hollywood and Vietnamese films, often war-themed, carefully edited to avoid showing any human presence.

The placement of the screens, together with mirrored panels, are inspired by the different points of view that are present in a shanshui painting, Nguyen says, a strategy that she has adopted to destabilise “the persistent power relations in postcolonial Vietnam”.

They cared for many families’ children. Photo show reminds us not to forget

The foregrounding of nature, and of sounds, is also an attempt by Nguyen, who is used to seeing the world through a single lens, to seek out a less egotistic, less human-centric perspective, she says.

The way the work was commissioned also serves as a model of how multiple parties can come together in a less hierarchical, binary relationship.

The plan was for M+, together with the Han Nefkens Foundation, Mori Art Museum and Singapore Art Museum, to co-commission a work with the aim to open up the pool of knowledge and avoid institutional groupthink. Invited “scouts” at the four institutions compiled a list of artists’ proposals, from which Nguyen’s was unanimously chosen. Each institution then decided individually how they wanted to show the work.

Another, separate, co-commission is Indian filmmaker Amar Kanwar’s The Peacock’s Graveyard (2023), first shown at the Sharjah Biennial, in the United Arab Emirates. Like Nguyen’s work, this is also a multichannel piece, in which the narrative moves across seven screens.

In some ways, the exhibition could have gone further. While a good number of Hong Kong-born artists are featured, it would be nice to have some kind of sidebar that provides context regarding the city’s home-grown responses to shanshui, given the genre’s deep cultural roots here.

There is also a complete lack of context regarding the history, evolution and diversity of East Asian ink landscape art.

While the M+ curators make clear that the exhibition is about “echoes and signals” of shanshui, they seem too determined to avoid talking about the ink tradition directly.

He covers himself in a white sheet so he can use all 5 senses to paint

Shenzhen-based Liang Quan’s two works titled Hidden Fish in a Clear Stream (2013-15) demand a small photograph, at least, of the Song dynasty shanshui painting of the same name by Li Tang, or some explanation of why Liang’s abstract paper collages are thus titled.

In fact, any visitor unaware of the term, or the heritage, might not appreciate this thoughtful “expansion of the canon”, as the curators describe the exhibition.

A simple remedy would be a neighbourly collaboration with the Hong Kong Palace Museum, which sits just minutes away and has a repository of classical, “canonical” ink paintings.

Maybe, one day, these two silos will level their own walls.

“Shanshui: Echoes and Signals”, South Galleries, M+ Museum, West Kowloon Cultural District, 38 Museum Drive, Kowloon, Tue-Thu and weekends, 10am-6pm, Fri 10am-10pm.