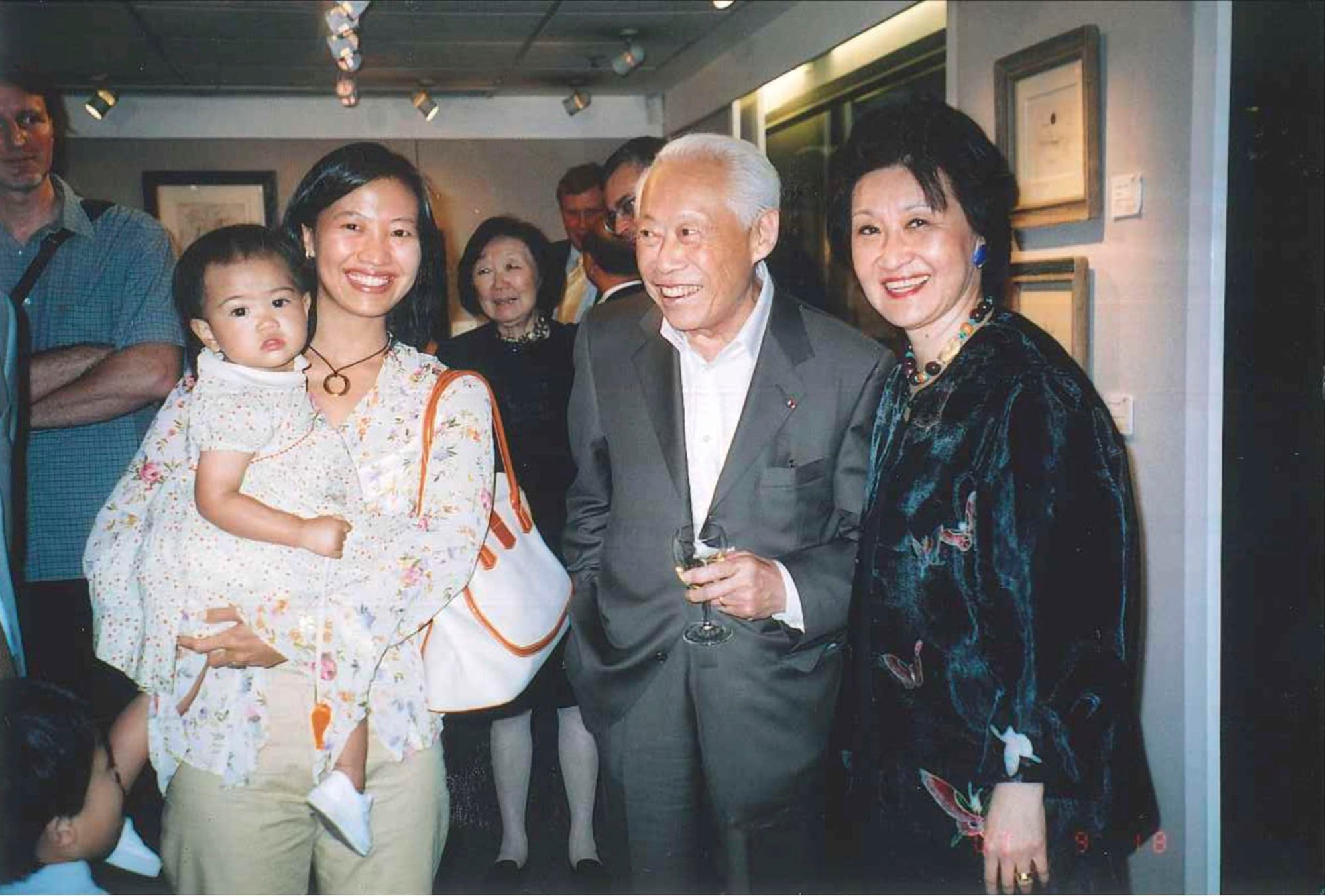

Profile | She’s educating America about Chinese art – Daphne King-Yao, niece of Tung Chee-hwa, on taking over her mother’s gallery, memories of home and cultural diplomacy

- Daphne King-Yao, granddaughter of shipping magnate C.Y. Tung and Tung Chee-hwa’s niece, has been surrounded by art since she was very little

- Today she runs Alisan Fine Arts, the Hong Kong-based art gallery her mother co-founded, which recently opened a branch in New York

Daphne King-Yao grew up in a world where art, family and business always overlapped. Her grandfather, shipping magnate C.Y. Tung, frequently travelled to New York for work and on these trips sought out budding young Chinese dancers and musicians.

“He would take them out to dinner and support them,” says King-Yao. “When my mother was young, she would often travel with my grandfather on these business trips. She even met [Chinese-French painter] Zao Wou-Ki back then.”

King had her work cut out for her when she opened one of the first art galleries in Hong Kong. King-Yao, then a young girl at Maryknoll Sisters’ School – now called Marymount Primary School – recalls her mother commenting that people would rather buy a designer bag than a piece of art.

“I wasn’t even 10 yet and already I was immersed in that world,” she recalls.

‘My life is a string of serendipities’: Hong Kong photo art gallery founder

In 1984, Alisan Fine Arts found a home in Wellington House at 3A Wellington Street, and the following year it moved to Holland House.

“He was very excited and started to unroll all these big works in our living room and soon our entire living room floor was covered by these colourful florescent paintings,” says King-Yao.

During the mid-1980s, she was at boarding school in the US. One summer holiday, she was with her mother at the family’s New York home in the Upper East Side when Walasse Ting, another celebrated artist of the gallery, visited.

As a teen, she was impressed with his colourful personality and the convertible he collected them in to take them to dinner in Chinatown.

“Walasse Ting paints these nude ladies with flowers in their hair and birds,” says King-Yao. “They are full of life, and he was like that.”

In the late 1990s, there were just five galleries, maybe less, and by 2011 there were more than 100

In 1991, she graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a degree in European history. Although there was an open invitation to work in the family business, the art gallery, her mum was not pushing her, nor was she in a hurry to come back.

Instead, she spent a couple of years in the New York advertising world before returning to Hong Kong and working with British advertising, marketing and public relations agency Ogilvy.

In 1997, just before the return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty, she left Ogilvy to work with her mother at the gallery – Walters had already left, in 1990 – and the adjustment, compared to working at a big agency where she already had a team reporting to her, came as a shock.

“My mum said I had to start at the bottom,” recalled King-Yao, “the bottom of a team of five where one was her receptionist and one was her PA.”

Two years later, she got married, and the following year her son was born, the first of three children. Her mum had made it clear that her children should come first, and she made them her priority, helping out with the gallery when she had time.

It was not until 2011 that she took over the gallery fully, by which time the art scene had exploded in Hong Kong.

“In the late 1990s, there were just five galleries, maybe less,” she said, “and by 2011 there were more than 100.”

Like her mother, King-Yao did not set out to chase trends and stayed close to the gallery’s main mission of promoting contemporary ink art, diaspora artists and some Hongkongers.

“It confuses your collector base and your clients if you start jumping all around and showing different things.”

I always thought Chinese art was mainstream but going there I realised it’s a big education process

On the flip side, having so many international galleries in Hong Kong makes it harder to attract young Chinese collectors.

“I’ve noticed that young Chinese collectors don’t look at Chinese paintings or Chinese contemporary art that much,” she said. “They end up collecting Western art because the big galleries are here, they woo them, they have parties.”

That said, the gallery itself has gone international, opening in New York’s Upper East Side in November 2023. This was not just because New York was so formative to King-Yao – her husband is from New Jersey and they have spent their summers there.

“I always thought Chinese art was mainstream but going there I realised it’s a big education process,” she said. “You really need to educate people to understand what it’s all about and where it’s coming from.”

In May last year, King-Yao was appointed chairman of the Asian Cultural Council Hong Kong (ACCHK), succeeding Michael Jebsen.

The ACCHK is a non-profit organisation that awards grants to artists in Hong Kong and China to visit the US for cultural exchange. King-Yao sees her appointment, as well as the New York gallery, as part of her mother’s legacy of promoting cultural diplomacy.

The ACCHK is now fully independent and no longer funded by the Rockefellers, an American industrial, political and banking family in New York. As a result, King-Yao’s mission is to create more awareness about the ACCHK and raise funds.

King-Yao’s eldest child has already graduated, while the other two are still at university. This has given her the opportunity to devote more time to the gallery and her artists.

Her husband has jokingly asked her why she is working so hard when he is thinking about retiring. However, with the New York gallery taking off and the Art Basel Hong Kong art fair around the corner in March, she is just getting into her stride.