How the contemporary Chinese art collection of a former Australian ambassador to Beijing was accidentally pieced together via ‘friendship and serendipity’

- Geoff Raby’s collection of 174 artworks donated to a Melbourne university ranges from ribald to rueful, with nods to the scurrilous, salacious and political

- Roughly half of that mostly contemporary trove of art is showing at Sydney’s National Art School until the end of March

Soon after assuming his post as Australian ambassador to China in 2007, Geoff Raby visited a restaurant in Songzhuang, Beijing, and was captivated by what he saw: oil paintings of cheerfully industrious pigs.

So taken was the diplomat by the works that he asked for an introduction to the artist. An invitation to Li Dapeng’s workshop followed.

“But it just so happened that on the afternoon we were going, Andrew Forrest was in town,” Raby says, referring to the Australian mining billionaire, who subsequently joined the workshop excursion.

“It was full of happy pigs building things,” Raby remembers of the works they saw. “Happy pigs building the Three Gorges Dam. Happy pigs building car parks and shopping malls. And Andrew bought this enormous piece of happy pigs building the railway to Lhasa.”

Raby laughs about seeing the painting again while visiting the headquarters of Fortescue, Forrest’s mining and energy company, in Perth, Australia, a few months later.

“I said, ‘Look, mate, I’d suggest you don’t have that in the waiting area because it’s politically sensitive.’ And he said, ‘You know we’re celebrating building railways. What’s wrong with you?’”

Shortly after – as the raffish economist, diplomat, consultant, author and curator tells it – the artwork was removed.

Raby’s fondness for the scurrilous – as well as the salacious and political – is evident in his collection of 174 Chinese artworks donated in 2019 to Melbourne’s La Trobe University, his alma mater. About half of that mostly contemporary trove of art is showing at Sydney’s National Art School until the end of March.

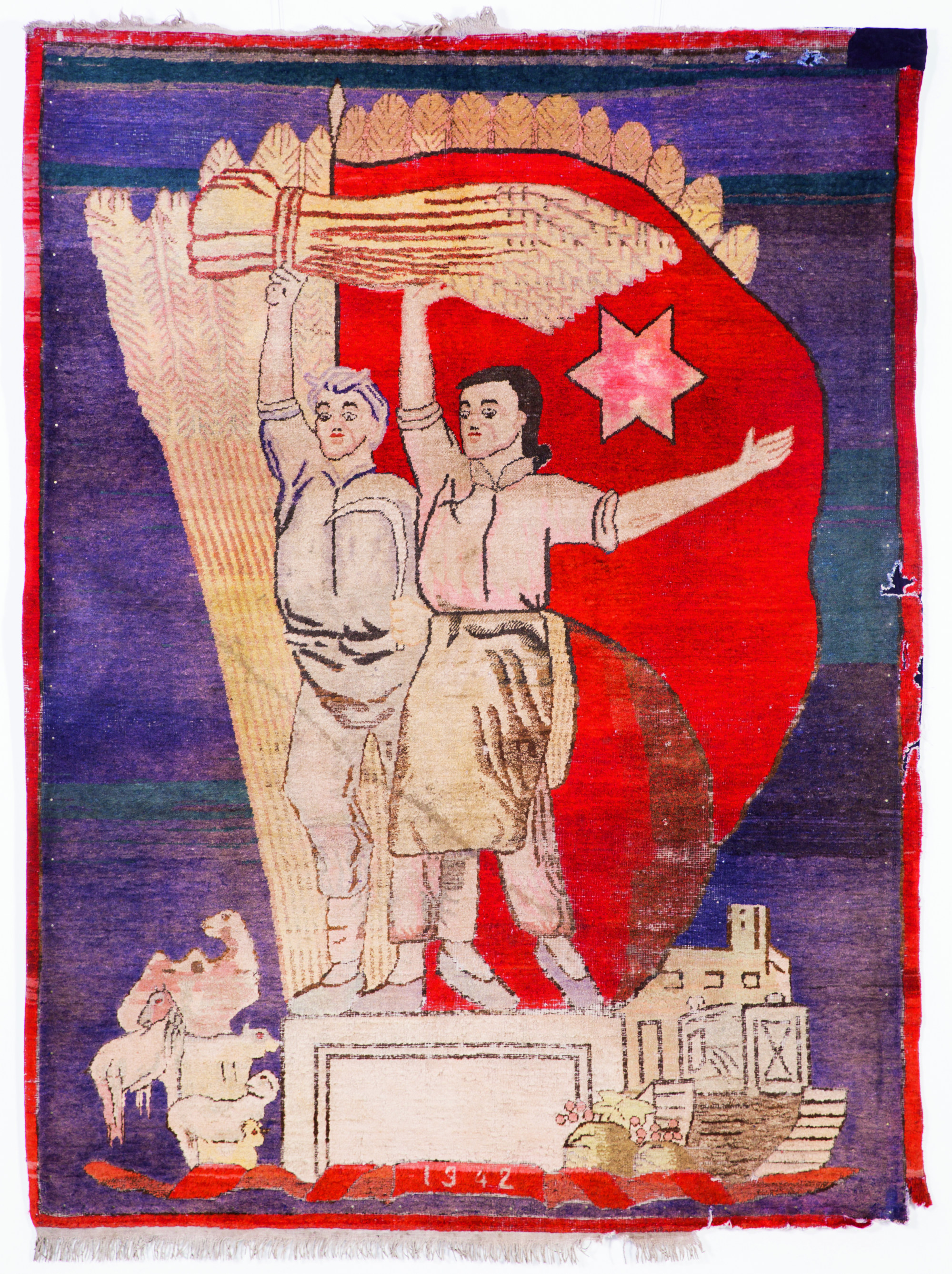

On display at “In Our Time: Four Decades of Art from China and Beyond” is everything from traditional brush-and-ink paintings to a 1942 carpet with Soviet motifs from Xinjiang, Chinese propaganda works, activist art before the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown in Beijing, and present-day creations including photography and sculpture. The ribald can be found among the rueful, while fashion rubs shoulders with performance art.

Li’s paintings are highlights of that show, in particular The Year of the Pig (2007), which features a pink porker in a yellow spacesuit.

“The moment I saw it, I knew [Li] was taking the p***,” Raby says.

Happy pigs are apparently a comment on the social contract between the Chinese Communist Party and the people it governs. The message seems to be: progress in the name of science and technology – but at what cost?

Does M+ show based on East Asian ink landscapes go too far or not far enough?

Still, during Raby’s four-year ambassadorial stint, The Year of the Pig hung in plain sight, latterly at his home in the St Regis Beijing, where he entertained officials regularly.

Raby arrived in Beijing in 1986, working as head of the Australian embassy’s economic section until 1991 before moving on to other positions in Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. By the time he returned to Australia in 2022, he had lived in China for almost 20 years.

His first acquisitions of Chinese art stem from those early buoyant years that were uplifted by the country’s open-door economic policy. Freedom and experimentation characterised art produced during the 1980s, when Chinese artists took cues from Western styles and art no longer served solely as an official political tool.

“Everything was new,” Raby says.

They reached out because we were available … And they reached out because we had money and an interest in buying their art

Nicholas Jose, a former cultural counsellor in the Australian embassy in Beijing and a colleague of Raby’s, was another witness to that period.

In the book accompanying Raby’s gift to La Trobe University, by curator and arts critic Damian Smith, Jose writes about Chinese contemporary art “emerging in Beijing in the late 1980s through a coalescence of graduates from liberalising art schools, newly self-styled artists from outside the academies, and foreigners, especially journalists and diplomats, who helped make introductions to the international art world. Geoff Raby was there at the beginning of that story.”

As ambassador, Raby was also there for “China’s coming out party on the world stage”, Jose says.

Get hands-on with Yoko Ono’s art of 7 decades in Tate Modern exhibition

Serendipity fed the narrative. “Accidental” networks of friends provided access to artists and their creations, Raby says, explaining that at the time he had no grand acquisition plans for investment or archival purposes.

“We gathered at parties to drink beer and smoke cigarettes. It was that sort of subculture that brought us together.”

It is the same message Raby served the crowd gathered for the opening of the Sydney exhibition. While his accumulation of Chinese contemporary art was not methodical, how it came together connects a sometimes chaotic and random collection.

This contrasts with Uli Sigg’s strategic acquisitions and subsequent donation of the bulk of his Chinese contemporary art collection to Hong Kong’s M+ museum in 2012. The 1,510 pieces acquired by M+ included 47 works bought from the Swiss collector.

‘My gift is for the long run’: Uli Sigg stands by M+ museum donation

Raby’s is a compilation of works by Chinese artists he came to know and sometimes befriend. Several subsequently emigrated to Australia after 1989 (although many later returned to China). Lending their support at the opening were, among others, Chen Wenling and Guo Jian.

Theirs was a world of cynical realism, a term coined in the ’90s to describe art imbued with social criticism but leavened by humour. There was also the closely related political pop, a genre that emerged in the ’80s and combined Western pop art with Soviet-influenced socialist realism, once China’s official artistic style.

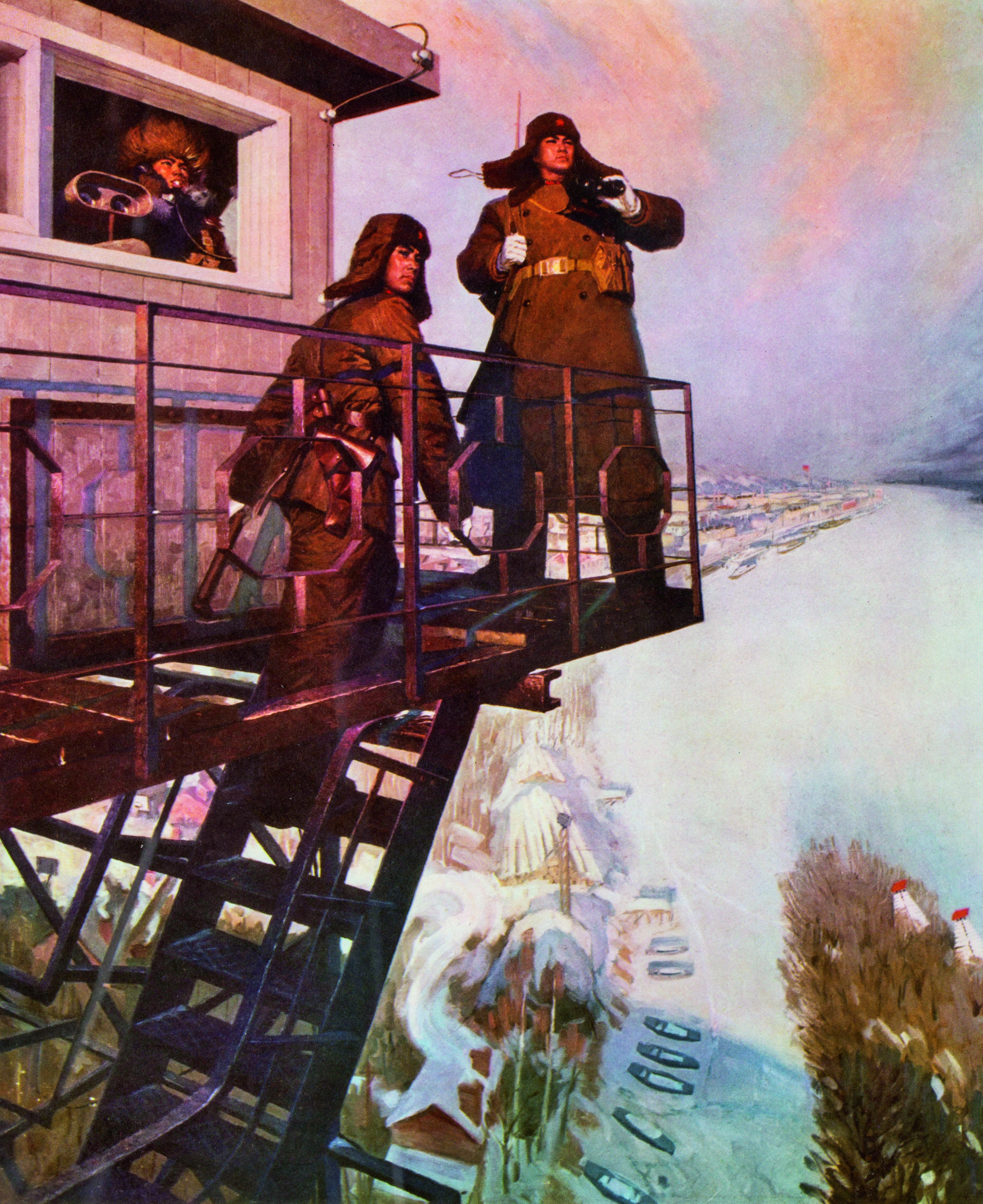

Near the exhibition entrance, Shen Jiawei’s Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland (1974) is a sobering example of Socialist Realism’s objectives. Mao Zedong’s fourth wife, Jiang Qing, liked the oil painting so much she had thousands of reproductions of the “icon of the Cultural Revolution” printed and distributed in China.

“What I have is one of those copies, but being an old friend of Shen Jiawei, he has annotated the piece,” Raby says.

Shen’s notes explain that the original had been reworked so that the three guards in the oil painting – protecting China from the threat of the Soviet Union – looked angrier and more heroic. After moving to Australia in 1989, Shen restored the painting to its original, less ruddy version.

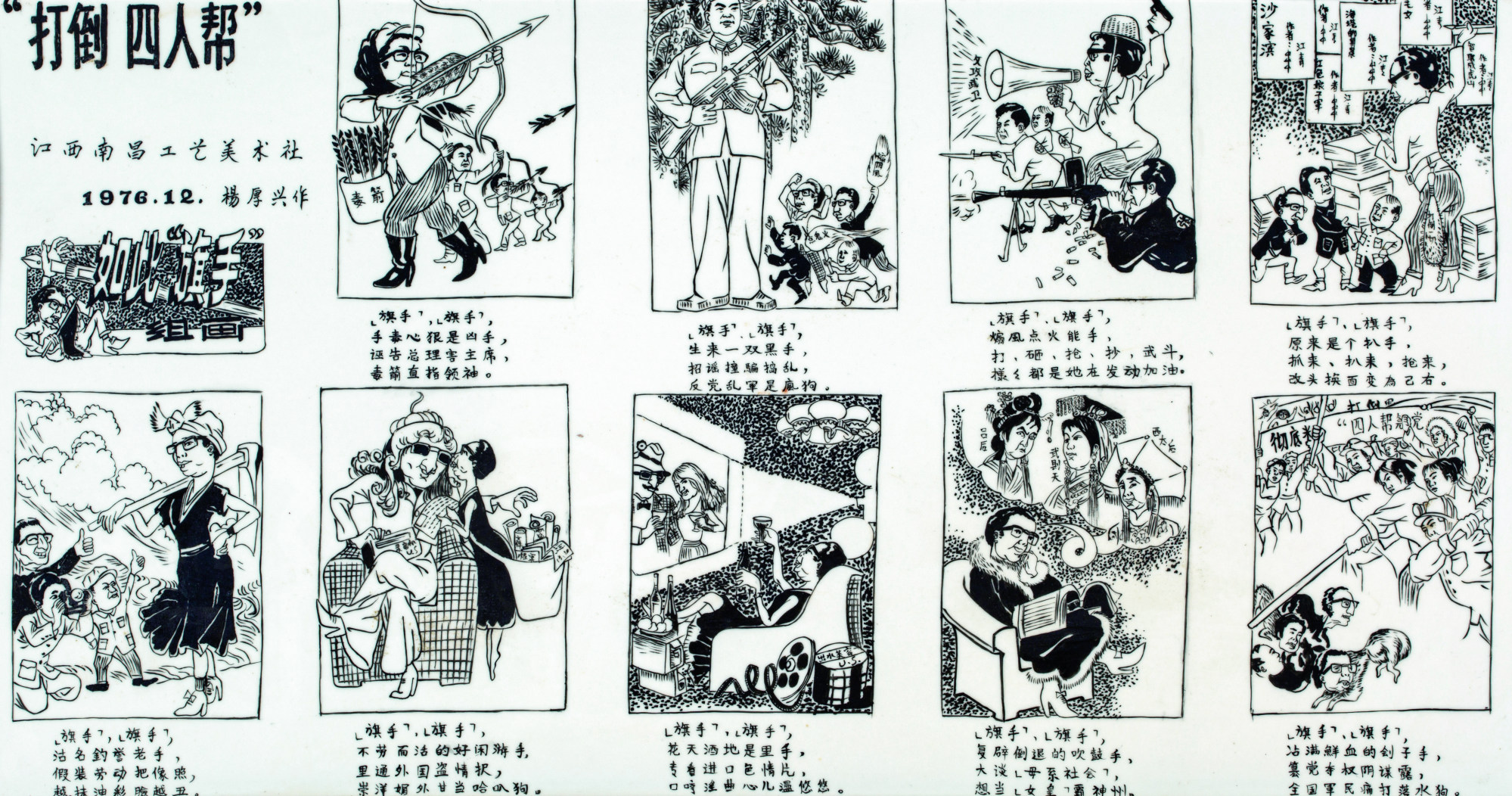

Jiang’s downfall is recorded in an unusual political cartoon positioned nearby. Titled Defeat the Gang of Four (1976), the work, by Yang Houxing (1915-1992), shows her mixing with Westerners and dreaming about reinstating China’s monarchy. Raby stumbled upon it while in Jingdezhen, the city in Jiangxi province dubbed the country’s porcelain capital.

“Many of my friends among contemporary artists had started to move from painting to sculpture and pottery,” Raby says. “I just happened to be at an antique shop, looked up and saw what I thought was a work on paper. And then it dawned on me it was propaganda art made on porcelain. So I had to have it.”

Raby would experience that urge innumerable times, which is why he credits intuition for guiding him in the works he bought.

Not lost on him was that the art being created reflected extraordinary social changes sweeping through China – although his former Chinese partner thought the collection “rubbish”, he jokes, and suggested that he “burn the stuff”.

Someone else with history on his agenda was Hua Jiming, whose exhibit, Chinese performance art (2009), celebrates with unruly sketches key moments from the art form’s 1980s beginnings. Among the interwoven acts depicted is Zhang Huan’s 1995 To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain. (A photograph and video of the performance are in the Sigg Gallery at M+, showing 10 artists lying naked on top of each other to raise the height of a peak.)

In the centre of Hua’s work is another record of a record, this time the artist’s impression of a photograph of Xiao Lu, gun in hand, firing at her exhibit, Dialogue.

That act, at the groundbreaking 1989 China/Avant-Garde show at the National Art Museum of China, saw Xiao Lu detained and the exhibition closed on its opening day. A 2004 black-and-white self-portrait recalling that moment – half her face an eerie photo negative – is called Open Fire.

As she wrote years later about the incident: “Four months later the Tiananmen incident took place … and my work became known as the first gunshots of Tiananmen.”

Fellow Australian and exhibition attendee Brian Wallace, founder of the trailblazing Red Gate Gallery in Beijing, describes the Raby collection as not only wide-reaching but also important.

About the first generation of artists graduating after the Cultural Revolution, Wallace writes in Smith’s book: “They were stymied by the lack of exhibition opportunity and frustrated by being frowned upon by the cultural autocrats.”

Which is why relationships were sealed at the exhibitions of “unofficial” art hosted by Raby and other foreigners in their apartments in the capital, even though, Wallace says, the artists’ audience was limited.

These amazing clay works will crumble right in front of your eyes

Did the artists also seek out foreigners to legitimise their work?

“That’s too academic,” Raby counters. “They reached out because we were available … And they reached out because we had money and an interest in buying their art.”

A genial portrait of Raby, nursing a giant bottle of Chateau Latour and a cigar, points to the evident camaraderie and win-win relationships made. By sculptor Chen Wenling, the 2014 ink and colour on paper also bears a warm inscription describing him as, among other things, “honest and playful”.

Little wonder Raby keeps returning to happy chance to describe his collection.

“It was based on friendship and serendipity,” he says.

In Our Time: Four Decades of Art from China and Beyond, The Geoff Raby Collection, is on at the National Art School Gallery in Sydney, Australia, until March 30.