Rewind book: Paradise Lost, by John Milton

Throughout history, snakes have been portrayed in literature - from Kipling's Jungle Book to Saint-Exupery's Le Petit Prince to Rowling's Harry Potter - as creatures of power, but most powerfully as Satan incarnate.

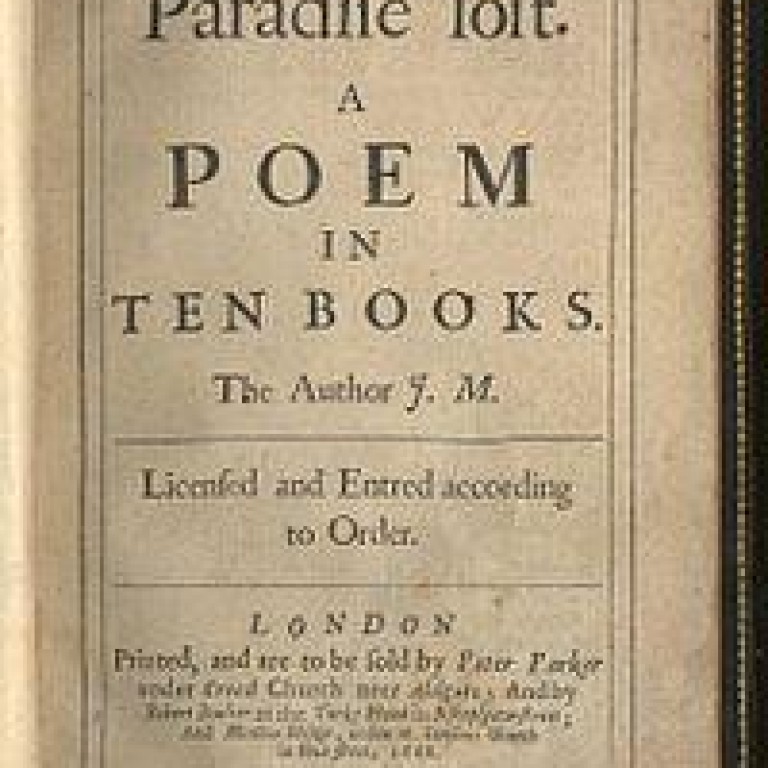

Paradise Lost (1667)

by John Milton

Samuel Simmons

Throughout history, snakes have been portrayed in literature - from Kipling's to Saint-Exupery's to Rowling's - as creatures of power, but most powerfully as Satan incarnate. "The Serpent suttl'st Beast of all the field, Of huge extent somtimes, with brazen Eyes," is how the snake appears in John Milton's epic poem .

Coming in the wake of the publication of the King James Bible in 1611, takes a scriptural tale and expands it into a masterpiece. Written in blank verse, originally in 10 books (but later expanded to 12) and following the epic tradition of starting in (in the midst of things), Milton's opus depicts the fall of man, and the serpent as the devil in disguise.

The snake epitomises deception and trickery. Satan takes its form to persuade Eve to eat fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, as expressly forbidden by God. Eve, in awe of a creature able to speak and reason as the serpent does, willingly eats in defiance of the Creator.

It is Satan's rhetorical skill and persuasive powers, then, which influence Eve, leading to "that fould revolt". When Adam follows suit, God punishes the pair by casting them out of Paradise. Satan as "th'infernal Serpent" is a power even God seemingly can't contend with.

Milton's purpose, as he states in book one, is to "justify the ways of God to men". Biblical references permeate English literature, but few harness them with such power as Milton does here. His central depiction of Satan as the catalyst for man's fall asks us to consider God's will, and the representation of both good and evil.

We must consider, then, too, what the Bible itself represents: the way the King James Bible was written transformed the way it was perceived as well. Dramatic voice and poetic form give power to the story from Genesis.

Milton's poem sparked criticism from the likes of Samuel Johnson, Sir Walter Raleigh and T.S. Eliot, who all rebuked its ideas and language. But it is a narrative rich in philosophical, spiritual and moral musings, and for all that God is the central figure, it raises questions about human reason, free will and potential too.

Milton - who was impoverished and blind by 1652, and had to dictate in its entirety - is one of the greatest English poets. Here, though, his most potent message is to warn of the power of words. In its wily poetical form, has us firmly in its serpentine coil.