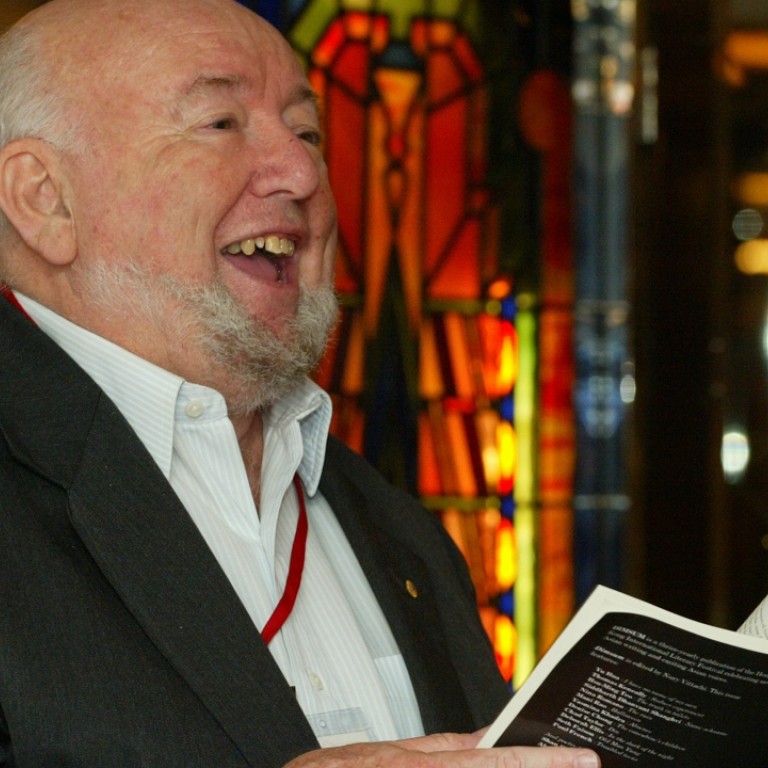

Book review: Napoleon’s Last Island by Tom Keneally is an intriguing tale of a world turned upside down

As with Schindler’s List, Keneally uses real events as a springboard to explore the tricks and turns of history and its relentless march past even the most significant people

by Tom Keneally

Random House

On a chance visit to an exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, author Tom Keneally discovered an astonishing Australian connection to Napoleon Bonaparte. When the exiled emperor was imprisoned on the south Atlantic island of St Helena, he spent three months as a guest of the Balcombe family. Napoleon’s Last Island is the intriguing tale of the friendship that sprung up between the Balcombe’s youngest daughter, Betsy, and the man known as the Great Ogre. A friendship that, in the end, saw the Balcombes exiled to Australia.

It is October 1815. The Balcombe family reside at their St Helena residence the Briars. William Balcombe works for the East India Company. His daughters, Jane and Betsy, live a free and easy life, interrupted only by occasional bouts of education. Betsy loves this tropical paradise and never wishes to leave.

When the British navy delivers Napoleon Bonaparte to the island, a captain informs William Balcombe that St Helena is to be the new Elba. “The Ogre is to be placed halfway between Europe, Africa and South America. This is the deepest pocket they could find to put the Universal Demon in.”

Keneally stages this contrast beautifully. Betsy’s island paradise is to be Bonaparte’s prison. Into her idyll comes a man feared, hated and admired in equal measure. But while repairs are made to his true prison, Longwood House, Bonaparte takes up residence in the summer house on the Briars estate.

For people such as the Balcombes, the chances of meeting a man such as Bonaparte on the global stage are infinitesimally small. The island confuses this sense of order and challenges the idea of authority. Europe may regard Bonaparte as a tyrant, but Napoleon and his entourage believe he is a poorly dealt with world leader.

As the political tide turns, the Balcombes, labelled as traitors to the British empire, are forced off the island. They too become exiles in the land of their birth. Their further exile to that island continent, Australia, in the guise of a government appointment for Balcombe as colonial treasurer, shows the extent of their downfall.

Napoleon’s Last Island is more than a work of historical fiction, it’s an account of contemporary relevance. In that sense, it’s typical Keneally. The author set his Booker Prize shortlisted book The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith during the Boer war, intending it as an allegory of the Vietnam war. Similarly, his 1974 novel about Joan of Arc, Blood Red, Sister Rose, is Keneally’s response to feminism, published at a time when Germaine Greer drove an international conversation about women’s rights.

As Betsy records her friendship with “Our Great Friend” (as the Balcombes call Bonaparte), her father William profits from the price hikes the emperor’s household demands bring. The islanders have never had it so good. The emperor is not so much a great tyrant brought undone, but an economic force and a charismatic, charming house guest.

Here’s another recurrent Keneally theme, that people have their moment in the sun before their lives are cast in shadow. The protagonist of his 1982 Booker Prizewinner Schindler’s Ark belongs in that category – by the end of the second world war, Schindler’s moment has passed. As British subjects, the Balcombes should revile the emperor Bonaparte, not be entertained by him. This confusion, that they are gaolers not intimates, contributes to their undoing.

Another Keneally trademark is using minor characters to tell a greater story. Through Betsy runs the fault-line between cultures: the British monarchy versus the dubious republican, the global battle writ small. It is her obscurity, her unimportance, which makes her the ideal lens.

Writing Napoleon’s Last Island from Betsy’s perspective allows Keneally to entertain readers with his trademark verve and impishness. Few can match him as a storyteller, and this story deserved his attention. Thank goodness future Balcombes valued the trinkets Napoleon gave them and thrived on this island at the bottom of the southern seas. For that, Keneally and his readers can be grateful.

The Guardian