Love After Love director Ann Hui accepts criticism of film for its casting of Sandra Ma Sichun and adaptation of Eileen Chang story, says ‘It makes me think how I can improve’

- Love After Love, about the downfall of a woman who moves from 1930s Shanghai to Hong Kong, was criticised in China for its casting and plot

- Now 74, Ann Hui says it shows she still has room to improve, and admits the difficulty of adapting Eileen Chang’s dialogue-heavy stories for the big screen

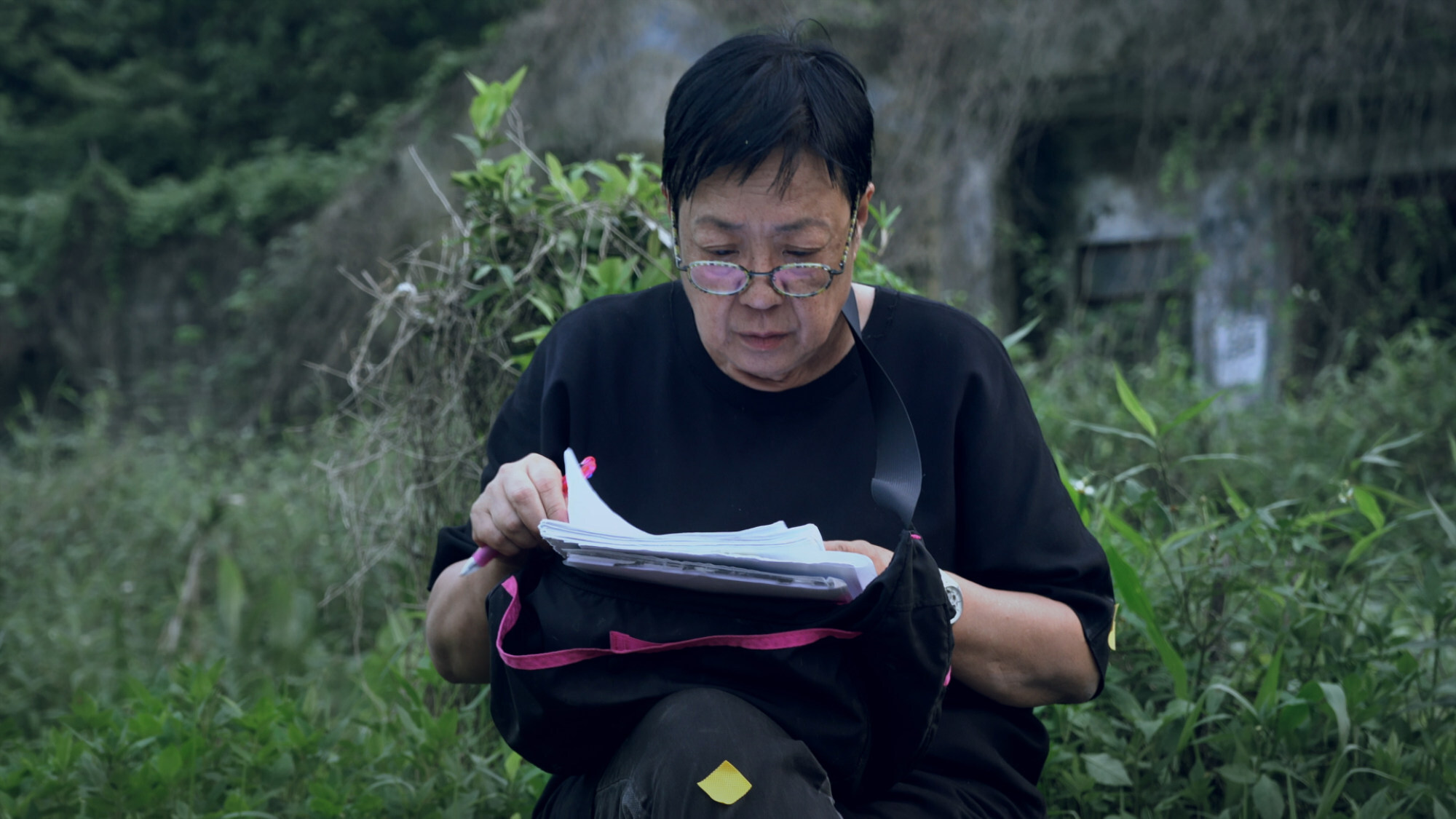

The response to Love After Love, the first movie by Hong Kong filmmaker Ann Hui On-wah since she won a lifetime achievement award at the 2020 Venice International Film Festival, has been harsh – unexpectedly so, according to the director.

The film (released in mainland China in October) was scripted by Wang Anyi and adapted from mid-20th century Chinese novelist Eileen Chang’s short story Aloeswood Incense: The First Brazier. It has been panned for straying both in its casting and plot. On Douban, China’s popular review site, it is rated 5.5 out of 10.

While Hui is frustrated by the negative response, she is trying to use it as a chance to figure out what went wrong. “The audience are entitled to their views. I find their reaction intriguing,” she told the Post in a recent interview in Beijing.

“No one said anything about the big amendments in the movie version of Lust, Caution,” says Hui. “Its ending was changed. The audience enjoyed the movie so much that they lapped up all the amendments. They forgot there were changes.

“My movie couldn’t make the audience forget the changes when they watched it. That’s probably our problem … it makes me think about how I can improve [in future].”

The 10 best films of Ann Hui, Hong Kong’s most celebrated director

Weilong’s descent comes after she moves in with her worldly-wise, gold-digging aunt (Faye Yu Feihong).

It was shot in Gulang Island in Xiamen, formerly a treaty port with a British quarter in Fujian province, southeast China. “The island has many flame and palm trees, which are typical Hong Kong trees,” Hui explains.

Love After Love is the third film Hui has adapted from works by Chang, after Love in a Fallen City (1984) and Eighteen Springs (1997). While the latter was lauded for its portrayal of two sisters who give up true love to be with men they feel nothing for, the former was criticised for miscasting Chow Yun-fat and Cora Miao as the leads.

Hui says Chang’s take on Hong Kong is what compels her to adapt her stories. “I read her works when I was around 30. Her novels are very enjoyable. They were written beautifully with a touch of magic. Her descriptions of Hong Kong closely resemble how I feel about the city.”

One of the biggest criticisms of Love after Love is the casting of Sandra Ma. When she took to microblogging site Weibo in 2018 to post her thoughts about Aloeswood Incense: The First Brazier, internet users decried her interpretation of the story for being far off the mark. Some compared it to mixing up Hamlet and Harry Potter.

Hui, however, has been impressed by Ma’s past movies, and says the media is being too harsh on her. “I hope she will be strong enough to weather the storm.

“The many criticisms of her [concerning Love After Love] have nothing to do with her. It’s not her idea to play the role in my film. It’s us who invited her to come on board … it’s me who miscast her. It’s not her problem.”

Hui says adapting written stories for the big screen is not easy. “[In adaptations], you cannot flesh out all the descriptions about the characters’ mental feelings in the original. The zingers in the books which I found to be impressive also cannot be fleshed out. If I use voice-overs to flesh out characters’ inner monologue in the books, the film audience finds it too obvious.

“Chang’s works have long and literary dialogue sections. Such dialogue is OK in a stage play, but strange in a movie. But dialogues are one of the best things in her novels. I have yet to overcome such problems for adaptations.”

The filmmaker reasons that the audience attacked her film because it did not turn out as they expected it would. “They think a literary movie should be solemn and serious [in tone]. However, Aloeswood Incense: The First Brazier can be made into a black comedy because the relationship between the main characters contains black humour.

“One scene sees [Weilong] leave the dinner table to get a phone call asking her to be a call girl. Her husband [George] then gets angry. The scene is filled with absurdity. But the audiences don’t think they should laugh during a literary movie. As a filmmaker, I should understand them more.”

“I feel my movies are not technically good enough. I hope I can make artistically better movies, though I don’t know whether I will get the chance to do it, as the movies I like to do are difficult to attract capital for and the industry is not good now [financially].”

Directed by Man Lim-chung, the film provides a rare personal look at the life of Hui, including her failed attempts as a commercial filmmaker in the late 1980s and her relationship with her Japanese mother.

While Hui likes the film, she says she doesn’t want the attention to be on her private life. “I didn’t know the film would be seen by so many people,” she says. “I thought it will just be shown in [Hong Kong] Arts Centre for a limited release. I don’t want people to treat me better after knowing about my personal life. It’s embarrassing.

“What kind of person I am has nothing to do with my films. I hope people will forget about it after a while.”

Love After Love screens on November 14 as part of the Hong Kong Asian Film Festival, and opens in Hong Kong cinemas on November 25.