How Hong Kong New Wave director Yim Ho, in films from Homecoming to Red Dust, explored rarely seen sides of China in the 1980s and 90s

- Fellow New Wave filmmakers such as Ann Hui are better known today, but the films Yim Ho shot in the 1980s and 90s were among that era’s most interesting work

- Homecoming contrasts urban Hong Kong life with that in rural China, Red Dust charts an illicit romance, and The Sun Has Ears is an offbeat historical melodrama

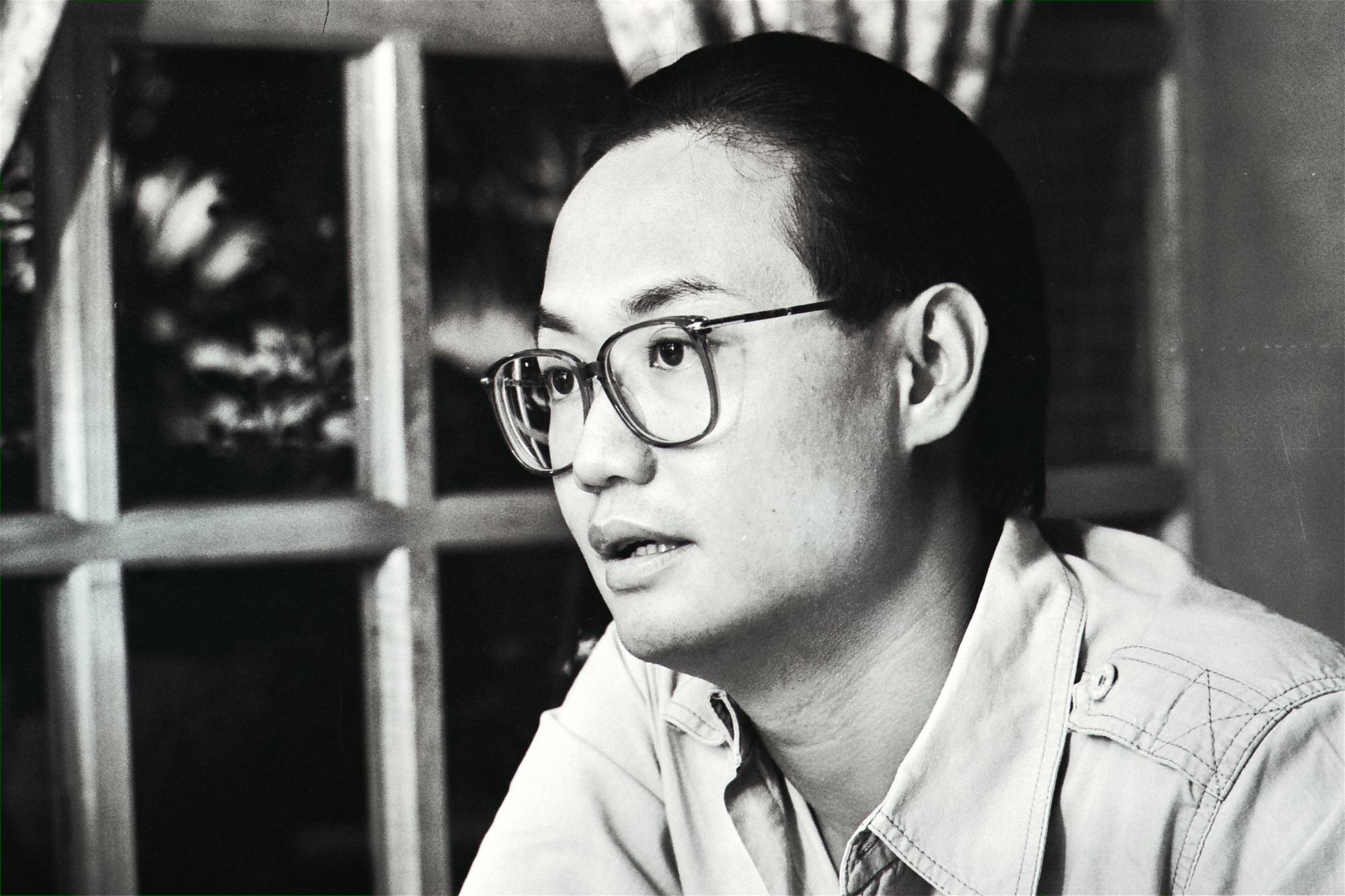

Yim Ho is less talked about today than his Hong Kong New Wave contemporaries such as Ann Hui On-wah, but the director made some of the most interesting films of the 1980s and 1990s.

Unusually for a Hong Kong director back then, Yim made his name with a series of films he shot in mainland China – his 1984 drama Homecoming was one of the first films to be shot by a Hong Kong filmmaker there.

Yim studied filmmaking in the UK, and cut his teeth working at Hong Kong broadcaster TVB. He moved into filmmaking with the comedic The Extras in 1978, before establishing his style with Homecoming.

Each of his films set in China is different; they include a social drama, a glossy historical romance, a true-life murder mystery, and even an ethnographical work.

How Tsui Hark made two of Hong Kong cinema’s most nihilistic films

The director, who told the Post he only made his earlier comedies to get a start in filmmaking, has always taken his work very seriously.

“Filmmaking for me is a process in which I am trying to learn more about myself,” he told this journalist in 1995. “I think it reflects the mental state I am going through when I’m making the film.”

Homecoming (1984)

Yim’s first film to be set in China tells the story of Coral (Josephine Koo Mei-wah), a Hong Kong businesswoman who returns to her family home in China to attend her grandmother’s funeral. She spends most of her time quietly trying to score points off her old friend Pearl, played by Siqin Gaowa, then China’s biggest movie star.

Yim contrasts the differing daily lives and aspirations of the two. Both are unhappy, but each feels that their own lifestyle is superior – Coral claims that her city life is more exciting, while Pearl responds that her simple village existence is more rewarding.

“Much to its credit, the film makes no overt moral or political judgment on Coral’s situation,” wrote Post reviewer Terry Boyce. “As a result of their renewed acquaintance, Coral and Pearl are forced to re-examine their lives. Closer scrutiny reveals cracks in both, the only difference being the way they cover them up.”

The style of Homecoming has much in common with that of China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers, who were just starting out in 1984. But it lacks the Fifth Generation’s critiques of the communist system.

Yim said in a later interview that working in China meant he had to abide by the restrictions on how he could depict life there.

Buddha’s Lock (1987)

Yim followed Homecoming with something completely different – a fascinating ethnographical drama set among the minorities in the Daliang mountains on the Sichuan-Yunnan border during the Second World War.

The story, which is based on a tale that Yim heard while travelling in China, is about an American soldier who is kidnapped and sold into slavery.

When US serviceman James Wood (John X Heart) tries to get involved in silver and opium smuggling, he’s tricked by his contact, and sold as a slave to the primitive Yi ethnic group. The Yi are aware of foreigners, but decide that they are more animal than human, noting that it’s rumoured they are descended from sheep.

Wood spends 10 years among the local tribes, learns to speak their dialects, and even finds himself a wife – although he is not freed until the People’s Liberation Army reaches the region and tells the tribes that slavery is now forbidden.

“Buddha’s Lock represents the only serious attempt at filmmaking in Hong Kong during the last year,” wrote the Post’s critic in 1987.

Yim told the Post that the film was concerned with “how we are controlled by destiny”.

Red Dust (1990)

Red Dust was something different again – a star-studded period romance set in an unnamed Chinese city the 1940s, and loosely based on an episode in the life of writer Eileen Chang.

Red Dust, which was shot in northerly Harbin, tells of an affluent novelist who falls in love with a Japanese collaborator during the Sino-Japanese war, and details the effect this illicit affair has on her and those around her.

The film is a well staged romance, but it lacks Yim’s usual insight. “Lin is intelligent and eloquent, but the scriptwriters have her spending more time mooning over the fact that ‘he has never said the words I love you’, than examining – or avoiding – her conflicting emotions on loving a traitor,” read the Post review.

“We knew very little about politics and the creation of the story was based only on a writer’s viewpoint,” Yim said in a Post interview in 1990. “But I found the story was quite close to the present situation in Hong Kong [in 1990] – that our society is also facing both political and social instability.”

The King of Chess (1991)

Tsui did not like the way the film was progressing, and took over directorial duties. The result is very uneven, with Yim’s scenes generally regarded as the best parts.

“It gradually dawns on the viewers that there is little dramatic connection between the two stories and the comparisons are often awkward,” wrote the Post’s Paul Fonoroff.

The Day the Sun Turned Cold (1994)

Changing tack again, Yim made the intriguing murder mystery The Day the Sun Turned Cold, which was based on a newspaper article he had seen in China.

The story is about a man who tells the police about the murder of his father – by his mother. The police procedural work is convincing, and Siqin Gaowa’s performance as the mother is superlative.

Hong Kong New Wave cinema: the directors and their groundbreaking movies

“Much of the dialogue was taken directly from official documentation” Yim said. “The challenge for me was where to draw the line between fiction and reality.”

The dilemma that Yim tries to resolve is the conflict between Confucian duty to the family and the law. “Should the son act according to the laws of society? Or should he be a rebel son of the Heavenly Kingdom, and defy its law?” Yim said.

The Sun Has Ears (1995)

The Sun Has Ears, which is set in rural China during the warlord era of the 1920s, is a historical melodrama about a peasant woman (Zhang Yu) who is torn between a handsome warlord general and her scheming peasant husband.

“The film comes up smelling fresh due to its offbeat narrative style and constantly shifting alliances,” Derek Elley wrote in Variety.

It was a conscious effort to do something new, Yim told this journalist. “In my earlier films, the characters weren’t that likeable. But after studying US films, I realised that the audience wants to like the lead character. So this time, she is likeable,” he said.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.