Dune speaks of climate change, war and resource loss. It’s not just a story – it’s a warning about our world

- A group of indigenous people wage war against the colonisers mining their land of a precious resource. Is Dune talking about Arrakis or our own world? It’s both

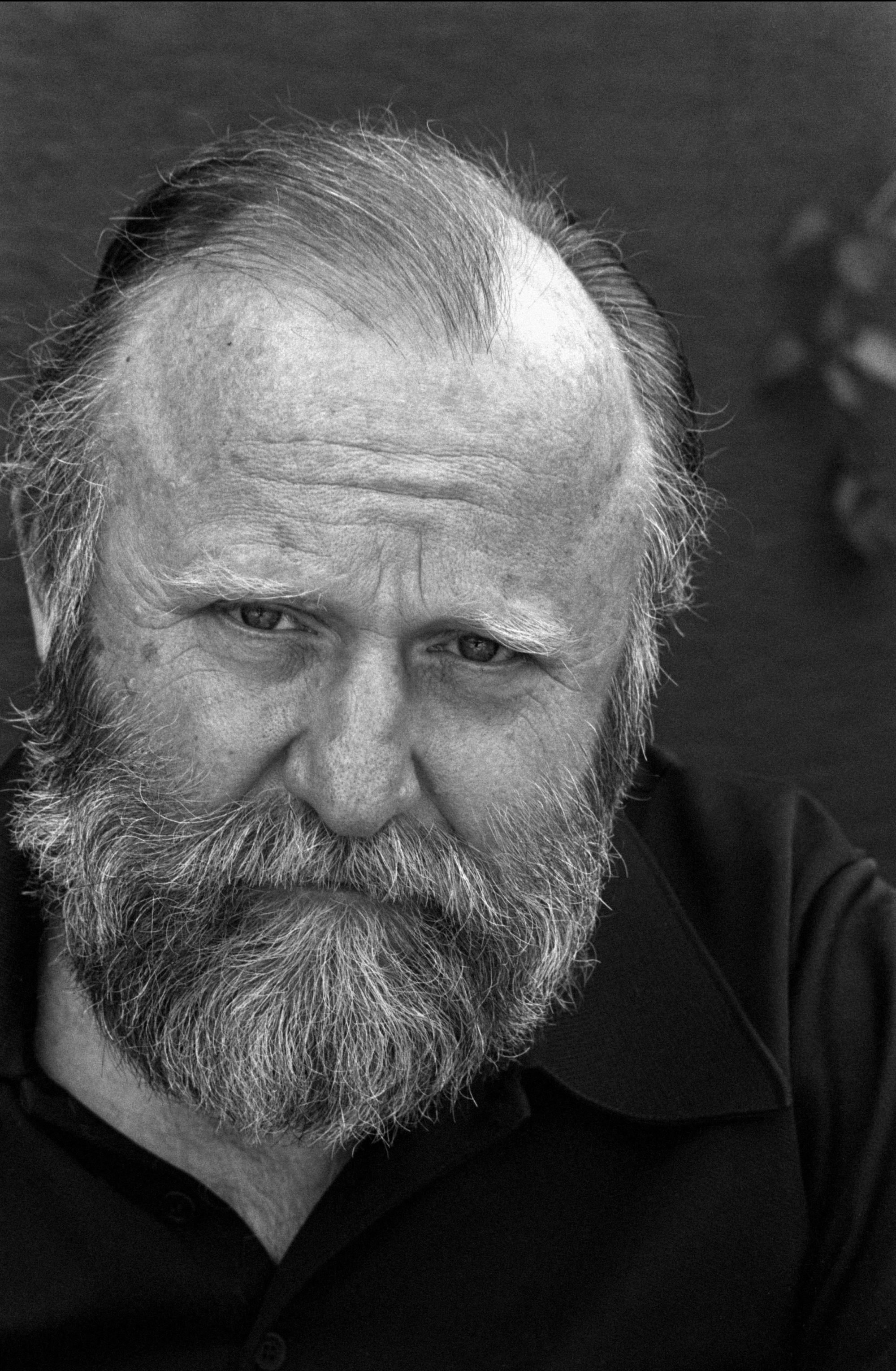

- The story’s author, Frank Herbert, intended his novel to be a cautionary tale of why we should take better care of our planet and warns against hero worship

This article contains spoilers

House Atreides has fallen. Duke Leto is dead and his son, Paul, lives in hiding, gathering his strength and awaiting the right moment to leave the Fremens and reclaim his birthright from the twisted Baron Vladimir Harkonnen.

Will our hero succeed? Is he a hero at all? What new challenges must he confront living among the dunes, storms and sandworms?

The book has amassed quite a loyal following since the novel’s debut in 1965. Herbert served as an early pioneer of science fiction with a climatological and ecological spin – “cli-fi” as folks in the know call it.

A native of Tacoma in the US state of Washington, Herbert was not the first to explore the subgenre, but his insights carry over into today’s world better than most. He cemented an uncannily prescient, even chilling, legacy for his most beloved work.

Without spoiling the second half of the story too much – part two of the screen adaptation of Dune by Denis Villeneuve is now showing – let us take a look at some of Herbert’s most enduring warnings.

“It’s not a hopeful book, it’s a pessimistic book,” says Devin Griffiths, an associate professor of English and comparative literature at the University of Southern California in the US. “It’s deeply critical of business as usual.”

Dune: Part Two – Denis Villeneuve’s sci-fi sequel is a masterful epic

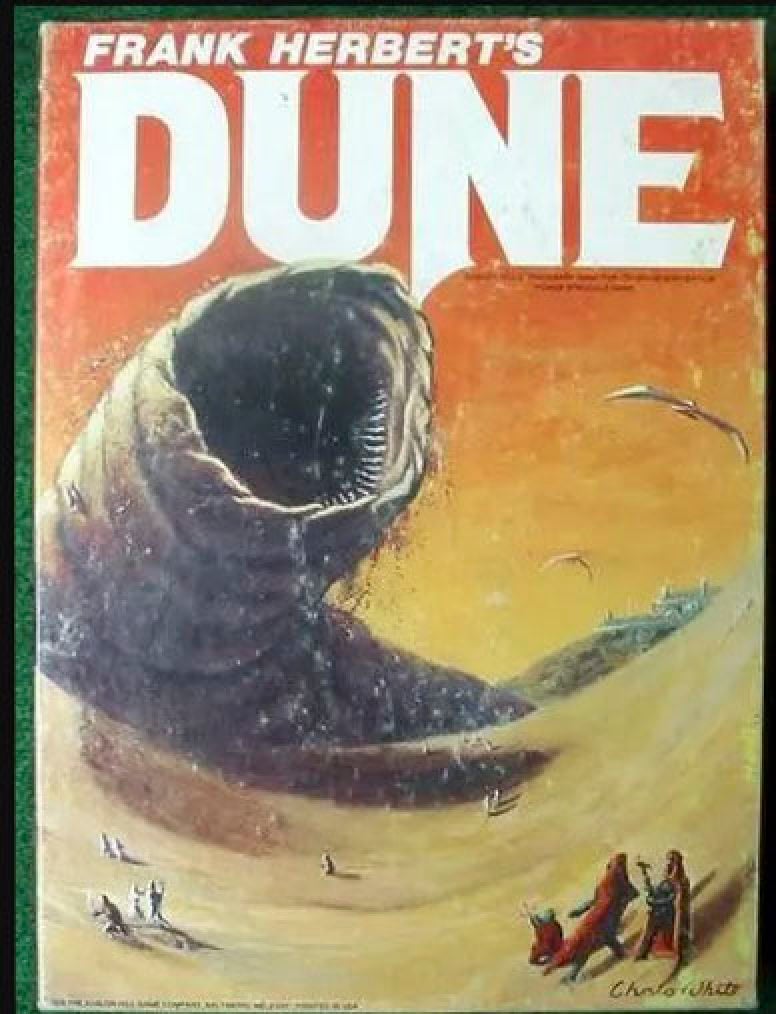

In the story, we have got a barren and dry planet covered in sand, occupied by the indigenous Fremen people and imperial colonisers who occupy the northern hemisphere and harvest “Melange”, also known simply as “spice”.

Melange is a drug, sacred to the Fremen and precious to the broader galactic empire because it enables interstellar pilots to safely navigate through space. Without the spice, interplanetary economies would crumble and so too would the empire.

Therein lies the catch and the conflict. Not only do the Fremen detest colonisers mining their planet for spice and often attack them, the mining operation is also a dangerous activity in and of itself. Melange is a by-product of the massive sandworms that also inhabit the planet. These scaly creatures, 400 metres (1,310 feet) long and with thousands of long, razor-sharp teeth, attack the mining operations without fail.

Take the sandworms out of the equation and a few things about spice might start to sound familiar. This is a rare substance, found on foreign soil, needed for travel, underpinning entire economies, the building block of whole governments, something over which generational wars are fought.

This is a story of scarcity, power and violence, says Jesse Oak Taylor, an associate professor in the University of Washington’s department of English.

“You have to be trying really hard not to see these convergences happening around us,” Taylor says.

For his story, Herbert drew heavily from his time in his native region, taking into consideration both the ecology of the Pacific northwest and its indigenous people, Griffiths says. He also took inspiration from the Aboriginal Australians, the Bedouin of Northern Africa, and the Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania.

As with these peoples, water in Dune is a scarce resource among the Fremen on Arrakis, something to be conserved at every opportunity.

Take in the whole scene together and a picture emerges of a delicate climatological and ecological balance on Arrakis. To be sure, it is a harsh planet that has chewed up colonisers for as long as they have invaded the place.

While Atreides is living in the desert, learning the Fremen way, his mother stokes the flames of an ancient prophecy among the community, convincing them that her son is their chosen one. They rely on that prophecy and religious fundamentalists who believe in it to seize power.

Does Atreides use this prophecy to defeat the Harkonnens, who are objectively terrible? Yes, but his ascendancy results in a deadly, intergalactic holy war.

Herbert wrote about his distrust – hatred, even – of hero worship and how it influenced Dune.

“Don’t give over all of your critical faculties to people in power no matter how admirable those people may appear to be,” he said. “Beneath the hero’s facade, you will find a human being who makes human mistakes. Enormous problems arise when human mistakes are made on the grand scale available to a superhero.”

“You find your own solutions,” Herbert wrote in 1980. “Don’t look to me as your leader.”