Review | Yan Lianke’s Cultural Revolution novel of love and hate is a visceral, violent triumph

- Born into violence and destined for a violent death, the hero of Yan Lianke’s novel embodies the self-destruction inherent in revolution

- Mixed in with Gao Aijun’s bursts of radical politics are erotic encounters with a mistress. Which comes first, love or revolution, Hard Like Water is asking

Hard Like Water by Yan Lianke, translated by Carlos Rojas, pub. Grove Press

Hard Like Water is a novel about love and revolution. At least, this is a short and simple summary. As is hinted by the title’s Taoist paradox, Yan Lianke’s story spins love and revolution into ever-shifting circles that are, by turns, intimate and constructive, joyful and erotic, while at others seem contradictory and oppositional, deceptive and destructive.

Yan isn’t the first writer to pair the passions that fire radical politics and life-changing sexual infatuation. As his long-time translator Carlos Rojas writes in an epilogue, Hard Like Water updates a literary genre popular in the 1920s and 30s: “revolution plus love”. The question Yan asks of this construction is: which comes first, the revolutionary or the lover?

Our hero is Gao Aijun, who is born on the same night that Japanese soldiers murder the male population of his hometown, Chenggang, in the Balou Mountains (familiar Yan territory). Among the victims is Gao’s own father, killed as he steps outside to call the midwife. This conflation of birth and death is the first of many uneasy oppositions: love and hate, male and female, city and countryside, or as Gao tells his son, “Without destruction, there can be no creation.”

Thematically, Yan files all these polarities under two main headings: the personal and political. His own name, Aijun, means “love the army”; he will name his son Hongsheng, “born red”, and his daughter Honghua, “red blossom”.

By a similar token, it is the formative loss of his father combined with the family’s marginal social status that will drive his later revolutionary fervour: Gao describes his father’s “intestines soaking the soil of our homeland, and igniting the vengeful anger of our People”. Equally, his urgent desire to destroy the town’s Memorial Arch is spiced by Gao’s dislike of the dominant Cheng clan.

Hunger, executions, escape to Hong Kong: a Chinese childhood

Indeed, his first explicitly political act, to join the army, is inseparable from personal feelings. Enlisting is part of the price he must pay to fulfil his ambitions of becoming a village cadre. Others include marrying the daughter of Chenggang’s branch secretary and producing a child. This Gao duly does, although he makes it clear he doesn’t see his wife as a lover so much as a meal ticket.

This uneasy metaphor prepares us for what happens next. Gao returns home with chip firmly on shoulder to a wife who defines foreplay as the un-Communist ravings of a “hooligan”. Gao has already been transformed in any case, falling in love at first sight with Xia Hongmei, whom he finds sitting enigmatically on some railroad tracks. Their physical attraction is instant and intense: there is a great deal of simultaneous trembling, electric shocks and pheromone aromatherapy. “I had never smelled such a scent on the body of my wife,” he notes in a hint of things to come.

What seals the erotic deal, even at this tentative stage, is their shared faith in Mao Zedong Thought. This lends their flirting a distinctly peculiar tenor. When Xia asks for an item of Gao’s army clothing, he replies, “My class compatriot, I’m truly sorry, but when I was demobilised I was given only two sets of clothing.” Hardly Valentine’s Day material.

Things get even stranger when they indulge in a charged bout of footsie, which shuttles strangely between fetish and political allegory: see Gao’s rhapsodies on her toenails “painted in brilliant red”. Their growing frenzy climaxes (the word doesn’t seem too strong) with the extraordinary line, “We stared at each other, our gazes like blood-drenched swords,” echoing Gao’s earlier comparison of women to poison.

Tragically for everyone involved, but particularly Xia’s husband, the underlying violence isn’t merely metaphorical but prophetic. We know from the start that the story ends badly: we first see Gao with “the muzzle of a loaded gun [placed] against the back of my head”.

Yan Lianke and the struggle to survive in mid-20th century China

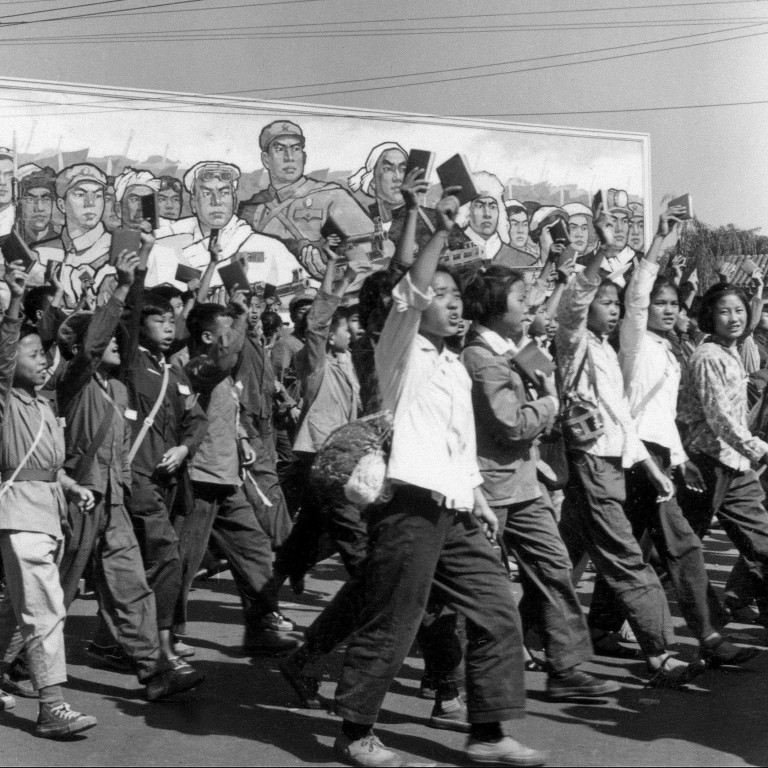

That the people threatening to shoot are “invoking the reputation of the revolution” reminds us of another of Yan’s central truths. Revolutions, by definition, revolve in self-destructive cycles: “Dragons beget dragons, phoenixes beget phoenixes.” Gao is referring specifically to Japan’s invasion of China, but he might as well be describing the self-immolation of the Cultural Revolution.

Whether these turns of history’s wheel propel you forward, or run you over, is down to timing, chance, and matters of geography, economics and society. But in Hard Like Water at least, they are also tests of character. “What kind of person did I want to be?” Gao asks not once but twice, before offering the same answer: “honesty”. Ironically, his greatest flaw is his failure to be honest with himself.

When he puts his experience as a railway engineer to good use and digs a “nuptial chamber” for himself and Xia underneath Chenggang, he calls it a “revolutionary tunnel of love”. Except, the “divine” underground retreat that he wants to be a symbol for his own misunderstood principles is, in reality, an admission of his own guilt, lies and hypocrisy. Why else keep it a secret?

“Revolution requires that we endure hardship and sacrifice,” Gao lectures his small band of would-be supporters. “It requires that we set aside our personal and family interests, and continually fight selfishness and repudiate revisionism.” Almost in the same breath, he adds: “However, the revolution is also capable of considering everyone’s personal and family interests.”

Gao is not the first human to become confused about the fine line dividing the means justifying the ends from having your cake and eating it, too – and he won’t be the last. That Hard Like Water presents him as sympathetic as well as grotesque, and weighs the senseless waste of the Cultural Revolution alongside its horror show, is testament to Yan’s vast talent. We would do well to read it closely today.