‘Keanu Reeves was all we had’: literary fantasy author Shelley Parker-Chan on growing up without role models as a queer Asian kid in Australia

- Identity was an issue for Shelley Parker-Chan growing up, and informs her debut novel, a ‘queer reimagining of the rise to power’ of China’s first Ming emperor’

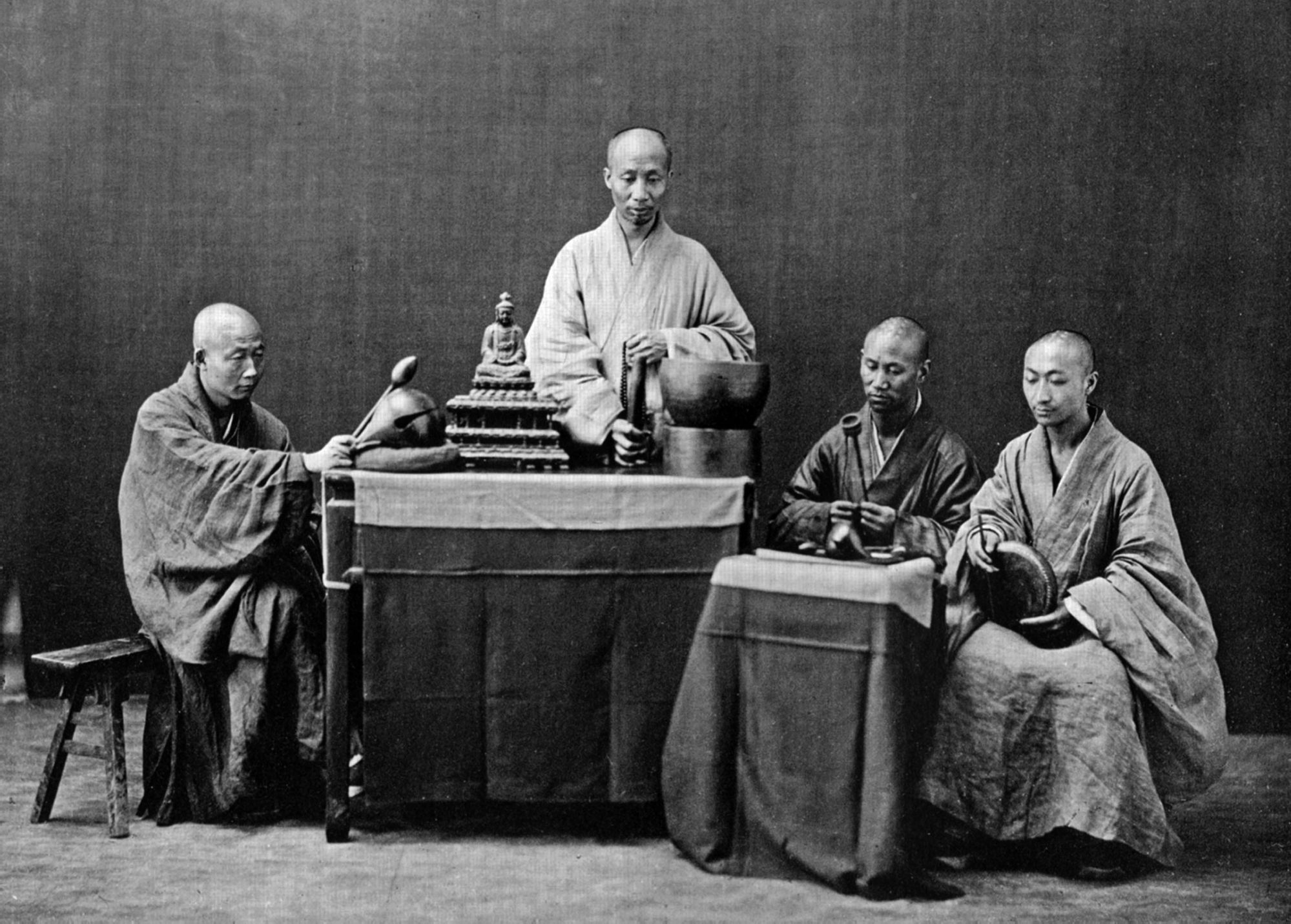

- She’s always had a thing about monks, she confesses – which is why they loom large in a work that’s also a love letter to Chinese period television dramas

She Who Became the Sun by Shelley Parker-Chan, pub. Tor Books

Writers respond in all sorts of weird and wonderful ways to that classic question: where did you get the idea for your latest novel? But few responses can top the one offered by Shelley Parker-Chan about her brilliant debut, She Who Became the Sun.

“I was looking for a big sweeping story with high stakes and monks,” she announces from her home in Melbourne, Australia. “I am weirdly obsessed with monks. You are going to ask why?”

It seems rude not to. Why? “As a child I somehow latched onto this idea of the ascetic monk who is a good person because they do everything correctly. Obviously it is a fantasy and has nothing to do with the reality of monastic life. I have met a few nuns in my time, and they are very worldly.”

I usually describe the novel as a queer reimagining of the rise to power of the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty

As if to prove her point, Parker-Chan herself talks to me from a suitably monkish lockdown study (or “Harry Potter cave”) improvised beneath a staircase. Nevertheless, worldly monk is not a bad way to describe Zhu Chongba, her endlessly intriguing protagonist who finds sanctuary from a life of poverty, starvation and violence in a nearby Buddhist monastery.

At the same time, monk is only one of many identities Zhu adopts during her dizzying ascent to supreme ruler of a 14th century, parallel-universe China. Another might be a dead ringer for the real-life Zhu Yuanzhang, better known as the Hongwu Emperor.

As the eagle-eyed reader of pronouns might already have spotted, the most intriguing of Zhu’s identities, and the biggest difference between historical fact and Parker-Chan’s historical fiction, is that Zhu was born a girl.

“I usually describe the novel as a queer reimagining of the rise to power of the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty. It’s also a fun story about gender. And I wanted it to be fun, not a hit-you-over-the-head story with any particular message.”

As is hinted by that punning title She Who Became the Sun/Son, Zhu adopts her brother’s identity after their family is massacred by marauding bandits. What begins as a survival technique born from necessity evolves into a single-minded quest for “greatness” in defiance of a sexist culture and the fate foretold by a fortune-teller: that Zhu’s life will amount to “nothing”.

Like its hero-heroine, Parker-Chan’s novel is a beguiling hybrid of ideas and influences. Monks are only one of its many ingredients. “It’s a love letter to Chinese television dramas, which are the most addictive things on the planet […] full of drama and intrigue,” Parker-Chan says. “I wrote the novel because I couldn’t find that feeling in a book.”

This hint, that her writing is more than might immediately be apparent, is quickly confirmed. “The book is not really about historical China. The Mongol representation [in the novel] is terrible. They’re not really Mongols.

“They represent mainstream white Australian culture and a particular type of Australian masculinity that is held as the ideal. This excludes every other kind of masculinity, especially queer masculinity and Asian masculinity, which is often coded as queer or effeminate even when they are not.”

Parker-Chan’s credentials as an Australian outsider are impeccable. She was born in New Zealand to a Malaysian mother, who left Kuala Lumpur to continue her studies overseas. Parker-Chan was seven years old when the family relocated to Australia.

“I was raised quite Chinese by my mother in this little group of high-achieving, upper-middle-class Asians who played the piano and violin and got good grades. We kept to ourselves, but that did offer protection and gave me a sense of Chinese identity.”

Book review: ME – a mind-bending exploration of identity

Driven by a “stereotypical tiger mother”, Parker-Chan won a scholarship to a “fairly posh private school”, where she encountered Australia’s macho elite first-hand. “It was white boys with blond hair who could play football and row. If you were a queer Asian kid who’s not quite female and not quite male, where do you fit in?”

Starved of role models (“Keanu Reeves was all we had”), Parker-Chan tried to answer these questions of belonging by reversing her mother’s trajectory and moving to Asia. “Good old Australia,” she says wryly. “I left as soon as I could.”

She worked first as a diplomat, “which is a really fancy way of saying that I was an extremely low-level, bureaucratic functionary in the embassy”. Later she moved into international development, specialising in human rights, gender equality and LGBT rights.

Although she travelled extensively across the continent, Parker-Chan lived for the best part of a decade in East Timor and then Indonesia, where she met her spouse and began raising their daughter (now aged nine), before moving back to Australia.

The experience was by turns formative and challenging. “There’s nothing like living in Asia to make a Western-raised Asian person realise they’re not actually Asian,” she says with a laugh, before describing her spouse, an expat who grew up in Indonesia, as “in many ways more Asian than I am. But then no one expects him to be Asian, whereas I thought of myself as Asian. Everyone was like, ‘You are not one of us.’”

If this provided a shock to the system, then Parker-Chan’s encounters with Asian media – above all, those addictive Chinese and Korean TV dramas – were more affirming.

“Just seeing everyone on screen being Asian. No one had to be the singular Asian who had the entire burden of representation. People were free to be human. It’s stunning and sad that this was the first time I’d seen it. It was truly eye-opening.”

Indeed it seems that, frustrated in her attempts to find an ideal home on either continent, Parker-Chan began to build one in her own imagination. This started as a reader, projecting dreams of belonging onto characters in fantasy fiction. “I always identified with the half-elves. Anyone who was a bit on the margins.”

From here Parker-Chan graduated to fan fiction. “This is often where queer writers explore romantic stories not represented in the mainstream.” These experiments in turn led her to join a writers’ group. “I think we were all looking for a book with a lot of emotionality, that represented queer sexuality and desire in a way that was cathartic.”

Unable to find such a book in bookstores, Parker-Chan decided to write one of her own that would reflect her many identities. “I couldn’t write a book that would appeal to the mainstream Chinese audience. That’s not who I am,” she says. “The bones of my novel are like a Marvel farm boy rise to power. It really is East meets West, which is what I am, too. The mixed-race, diaspora person.”

The good news for readers everywhere is Zhu’s story is not finished. Parker-Chan is hard at work on a sequel. As for Parker-Chan herself, it seems that She Who Became the Sun has provided that longed-for home from home. “I got all my identity issues out on the page. And that’s a pretty good form of therapy.”