Review | Will Cantonese struggle to survive like Welsh, Hawaiian and Tibetan languages? Author predicts a rough road ahead

- Repression of language was at the forefront of the cultural intolerance shown to native populations in Wales and the Hawaiian islands, James Griffiths writes

- Chinese rulers in Beijing have long promoted Putonghua over minority tongues, he notes, and the fight to save Cantonese could come sooner than many foresee

Speak Not by James Griffiths, pub. Zed Books

One recent study suggests that just over 3,000 languages are currently endangered – nearly half of those in use today globally. What causes language death? The process is, generally, gradual: an accelerating shift from an old linguistic system towards one with greater perceived utility or status. But, as journalist James Griffiths argues in Speak Not: Empire, Identity and the Politics of Language, this process is often driven by malign forces.

“Languages are not lost, they are taken,” he argues. “They are uprooted by malice or neglect, their speakers assimilated into a new tongue, or left to struggle in the space between the fading old and the out of reach new.”

Griffiths sets out to explore this thesis in three geographically diverse places: Wales, Hawaii and Hong Kong. Though thousands of miles apart, they are united by their experience of colonialism. Wales was “the first colony” of the English, Griffiths writes, while Hawaii moved from colony, to territory, to state.

Hong Kong’s history is more complex; a former British colony it has now been, in Griffiths’ words, “subsumed by the People’s Republic of China, which inherited and shored up the territorial reaches of the Qing Empire and has advanced an assimilatory language policy that previous Chinese rulers could only have dreamed of”.

Wales and Hawaii have both seen their respective languages brought to the brink by policies of repression, as well as the more subtle influence of inward migration by speakers of a global language. In Wales, this was part of a cultural intolerance that reached its zenith in the Victorian era.

As with native customs in other colonies, the Welsh language was dismissed as backward; an inhibiting factor on the progress of the people who spoke it. As one report put it, because of their insistence on using Welsh, “[a]lthough equally industrious with their English neighbours, the Welsh are much behind them in intelligence, in the enjoyment of the comforts of life, and the means of improving their condition”.

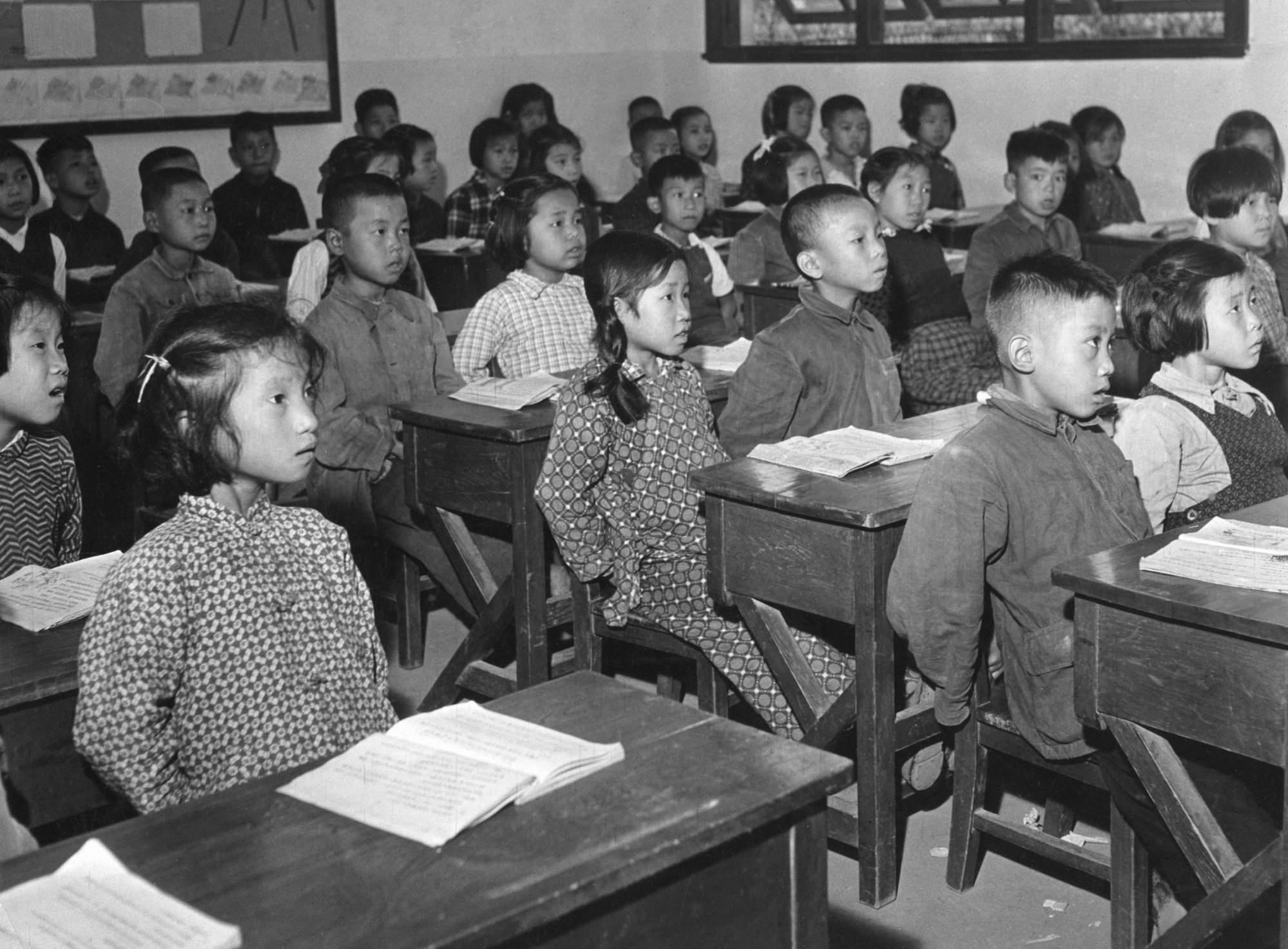

In both Wales and Hawaii it was reform of the education system that had the most deleterious effect on the native language. One Hawaiian missionary account explained the purpose of rules stipulating that English should be the sole language of the education system: “The present generation will generally know English; the next generation will know little else. Here is an element of vast power in many ways. […]

“As this knowledge goes in, kahunaism [a reference to Hawaiian religious figures, known as kahunas], fetishism and heathenism generally will largely go out.”

Griffiths’ account of the demise of Welsh and Hawaiian is clearly complementary. And the fate of Welsh offers, to some extent, a good news story: in recent decades national policies have rejuvenated the language.

How, though, does the story of Cantonese fit with these two oppressed languages? Cantonese is spoken by about 80 million people globally, mostly in southern mainland China and Hong Kong: it seems to be far from a dying language.

Griffiths walks the reader through the long debate in China around its national language. Despite its dominant linguistic position in China’s south, and the commercial significance of this area, there had long been scepticism of the virtue of encouraging Cantonese literacy.

The Yongzheng emperor was “exasperated by the unintelligible speech of officials from Fujian and Guangdong”, establishing institutes to teach them the lingua franca of the imperial court. When the People’s Republic of China was established, in 1949, it was Putonghua – the “common language” – that was adopted as the country’s “unified tongue”, drawing from the dialect and pronunciation of the north.

Putonghua established a “dictatorship”, “threatening other Chinese languages and dialects, including Cantonese”.

These warnings from the past should be carefully heeded, Griffiths comments. “Cantonese is facing rough decades ahead,” he concludes. “Its speakers may find themselves fighting for the survival of their language sooner than they expect.”