Review | Stitching is like drawing for Reiko Sudo, creative force of NUNO Japanese textiles, whose innovations she celebrates in a new book

- Reiko Sudo reflects on what goes into creating the extraordinary fabrics developed by NUNO in Japan, inspired by everything from jellyfish to chance to lentils

- The company, whose name means ‘cloth’, has brought material-making almost to philosophical experimentation

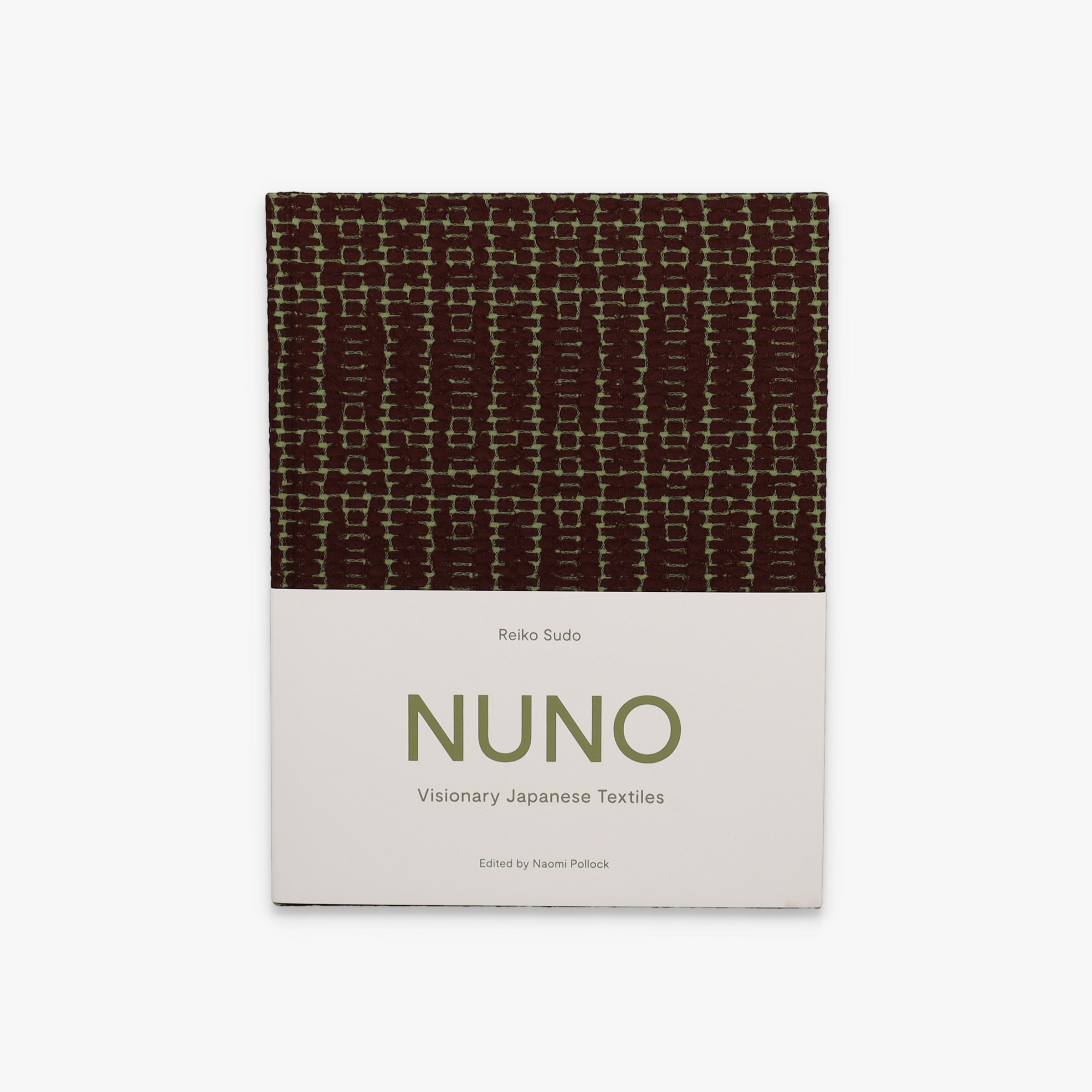

NUNO: Visionary Japanese Textiles, by Reiko Sudo and Naomi Pollock, pub. Thames & Hudson

NUNO: Visionary Japanese Textiles is an artefact in its own right.

Big, gorgeous, almost architectural, it is packed with images of some of the extraordinary fabrics made in the past 50 years or so by the textile company NUNO from its headquarters in Kiryu, two hours north of Tokyo.

Nuno is the Japanese word for “cloth”, but somehow by naming itself so simply, the company has brought material-making almost to philosophical levels of experimentation.

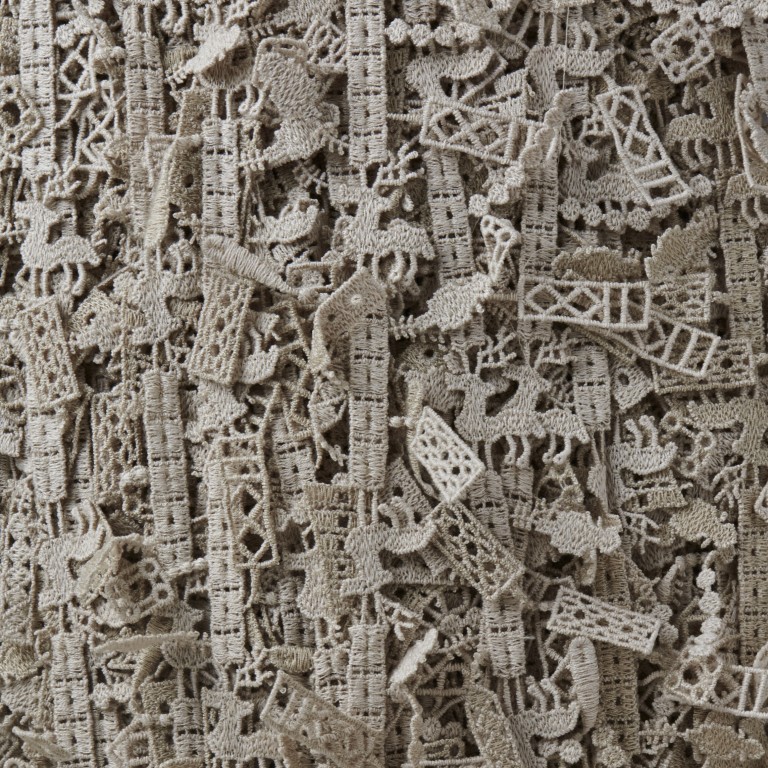

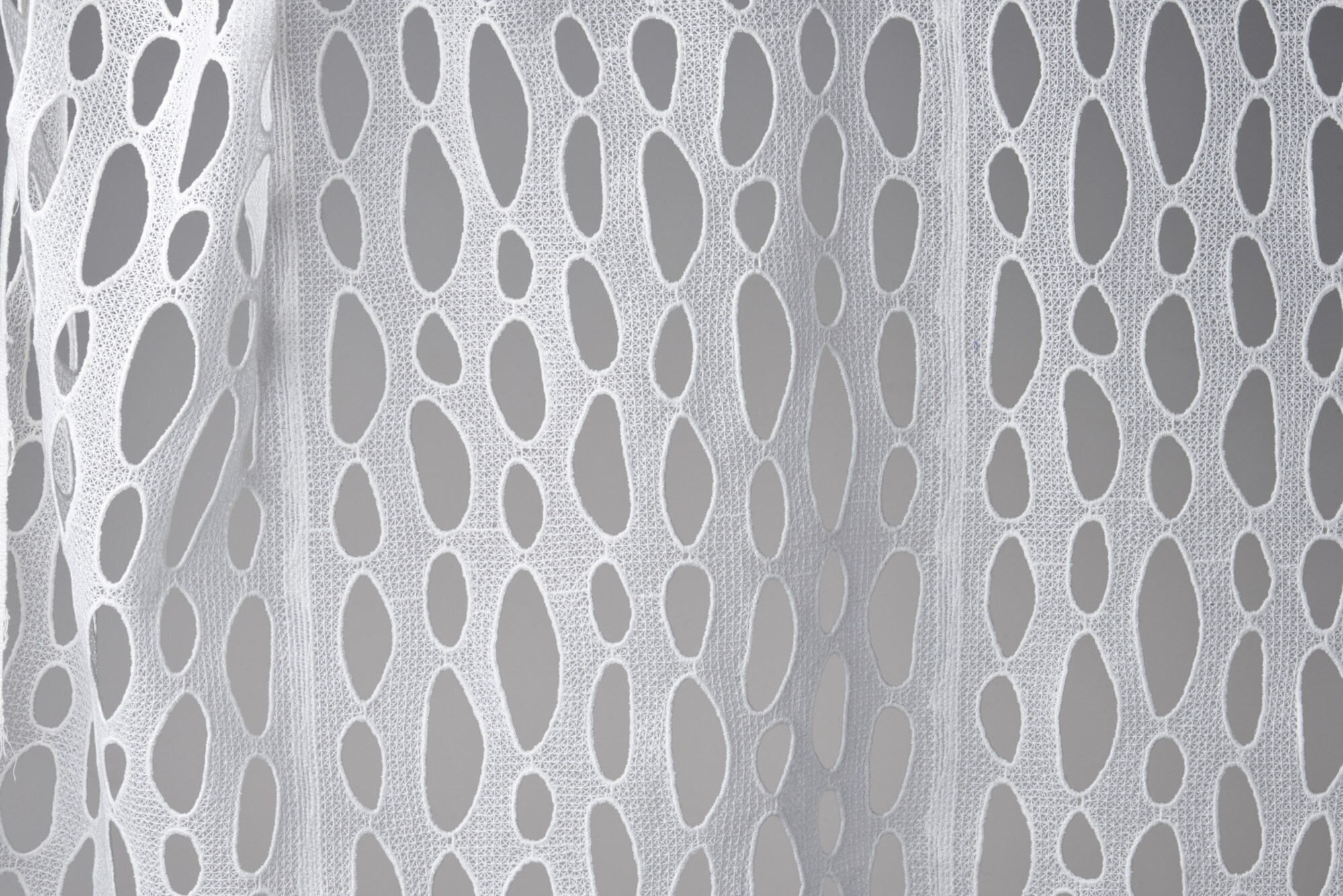

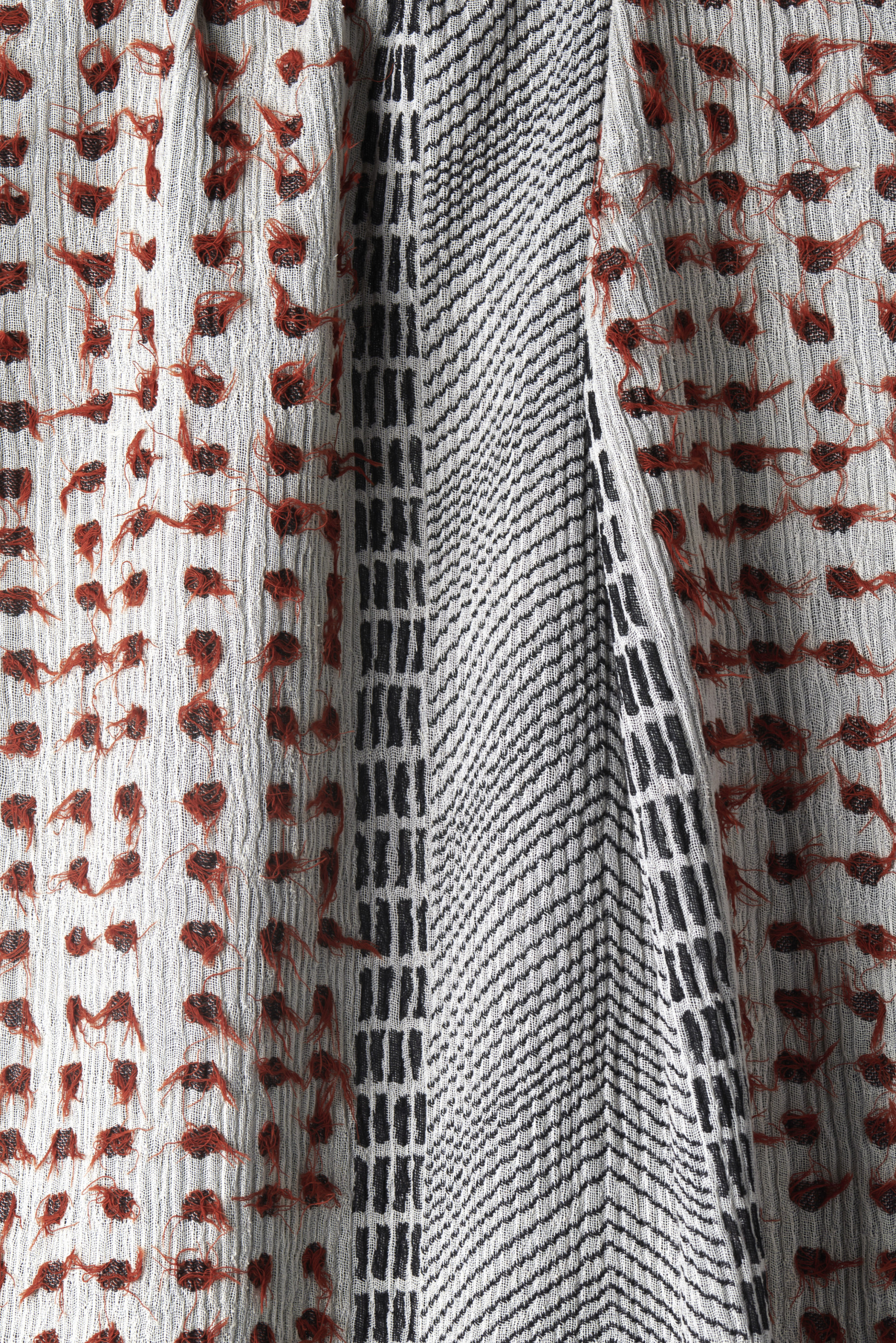

There are fabrics inspired by jellyfish. And scraps. And mushrooms and stringiness and chance. And disruption. And lentils. And heraldic beasts. And the travertine limestone whites of Turkish walls.

The book is organised by concepts. Fuwa fuwa (fluffy); shiwa shiwa (wrinkled); shima shima (striped); kira kira (a lovely word, meaning both dazzling and messy); suke suke (flimsy); zawa zawa (frenetic); and finally, boro boro, which means crumbly, or “the faded glory of things as they age”.

Put like that, it’s not just about fabrics: it’s also a metaphor for life.

Author Reiko Sudo has been the creative force behind NUNO for more than 30 years.

Explaining what characterises a NUNO fabric, she says, “It has to be something we have never seen before. And at the same time it has to be something we already know.”

I was doing hand weaving. But I was really bad. I was so slow. It would take me a year to do one piece

That innate paradox – of how the future somehow informs the past – could be said to be reflected in her personal journey as well.

She was born on almost the same day her maternal grandmother died. And from then on, family members would say, “Reiko, you’re doing things your grandmother couldn’t do in her life.”

Her grandmother had loved making traditional Japanese embroideries and tapestries, like the one that hung prominently in Sudo’s childhood home, one of her earliest textile memories.

When she was 10, her mother gave her an embroidery frame, and she realised that – for her – stitching was like drawing. She found a talent for making little stitched animals and figures.

“I had to,” she says. “My mother had six brothers and sisters. And my father the same. And that meant I had huge numbers of cousins. Unbelievable numbers. I couldn’t even count. And I’m the oldest. So you can imagine. I had to make so many gifts!”

With this early experience of running an embroidery production line, and also the sense of destiny literally hanging over her, a career in textiles was perhaps inevitable. But success didn’t arrive immediately.

“[After leaving university] I was doing hand weaving,” she says. “But I was really bad. I was so slow. It would take me a year to do one piece.”

An architect friend took pity, and whenever he was creating a new restaurant or office building, he would commission her to do a tapestry. “But he would say, ‘Sorry, Reiko, I don’t have the budget to pay you for a whole year’s work.’ Even my husband was saying, ‘Reiko you have to find a new job,’” she says.

She thought that textile drawings might be her thing, but the process of carrying drawings around and trying to sell them was painful.

Then one day, when she was 29 and in Tokyo, she looked into an art gallery window and saw an installation made of cloth. She stopped short.

Everyone in the textile world knew Junichi Arai, a man who had gone reluctantly into the family fabric business but who had made it his own, reconstituting traditional methods to make the new kinds of cloth needed in the 1960s and 70s. He was famous for supplying fashion designers such as Issey Miyake. But she’d never seen his work before in real life. The textures amazed her.

So she went in. To her surprise Arai was there.

“He asked me, ‘Why don’t you work with me?’”

At first she shook her head.

“I said, ‘What are you talking about? I don’t have experience selling things, and even my drawings I find hard to sell.’”

Why Reiko Sudo wants to reuse what other textile makers refuse

Later her friends said, “Reiko, why don’t you just help Junichi?” And her husband said “Well, you don’t have any talent as a weaver: this is a great chance.”

So she changed her mind. To Arai’s exuberant inventiveness she added her quieter, more patient approach, and together they made textile history, experimenting with all kinds of fabrics and fibres and science and techniques, and heating and melting.

And coincidence so often played a vital part in the creative process.

One day a needle broke on a sewing machine, and the stump punched through the fabric, ruining it. Instead of throwing it away she thought “how interesting” and created a way of making a textile that looks blurred, as if seen through a soft lens.

Another day, passing a colleague’s desk, Sudo saw origami doodles that intrigued her. Thirteen years later NUNO announced a loom that made peak and valley folds, and a technique where the holding threads were removed by heat, leaving the pleats in place “just like magic”.

The book is itself covered in NUNO fabric.

“We had a few ideas,” Sudo says.

One of those ideas was cotton redyed with indigo, like the fabrics they have helped fashion company reMUJI recycle.

Another was embroidery with a repeat pattern so big that each book would look completely different.

The one they chose, however, was a green and brown cloth woven to look like the cells of plants under a microscope.

The cloth is made of rayon and acetate, the former because it is often made from wood pulp, “just like books are made from wood pulp”, and the latter because it is the base material for photographic film.

The two together – reconstituted book, reconstituted film – symbolise a photography book reconceived in a marvellous way.

Which is exactly what this book is.