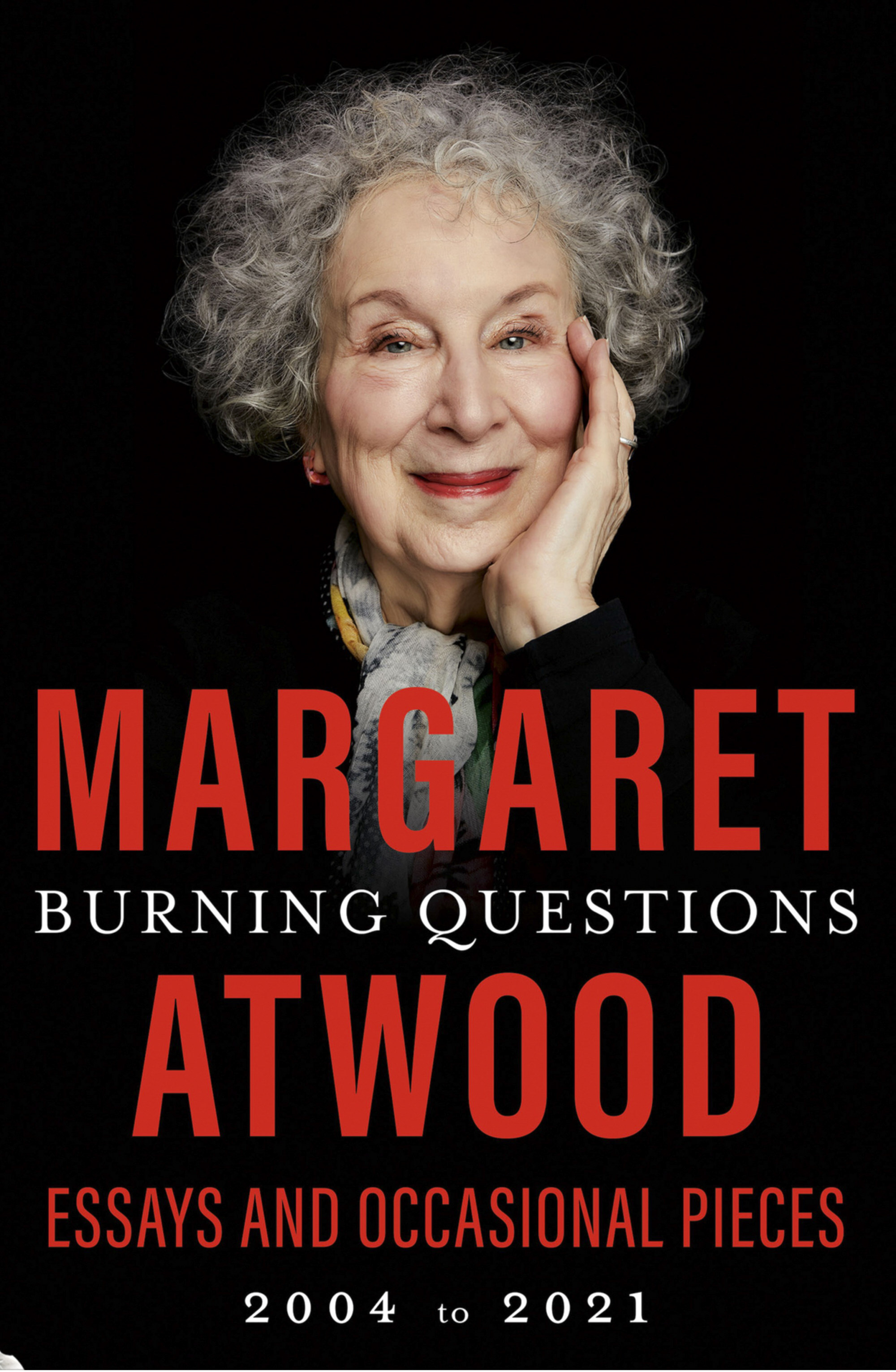

Review | Burning Questions, Margaret Atwood’s third non-fiction collection, is funny, fluent, wide-ranging and occasionally urgent

- Made up of ‘essays and occasional pieces’ composed between 2004 and 2021, Atwood’s collection spans everything from reviews to issues such as quarantine

- She eulogises fellow Canadian writer Alice Munro, encounters a polar bear, watches birds with her late husband and nurses him through dementia

Burning Questions by Margaret Atwood, pub. Doubleday

Add in graphic novels and children’s books, and all that remains for her to do is write a play and a cookbook.

Burning Questions is Atwood’s third collection of non-fiction: the others being Second Words (compiling work between 1962 and 1980) and Moving Targets (1982-2004). As Atwood writes in the introduction, the material in each volume owes almost everything to circumstance (or commissions): the political temperature of each period (civil rights and feminism, communism and free market economics, terrorism, technology, and Trump), to Atwood’s personal life (was she teaching or freelance, famous or getting there, a parent caring for young children, or a parent caring for her partner with dementia).

What this means for the reader is a mixture of personal appreciations (Franz Kafka, Shakespeare), introductions to classic works (Scrooge, Anne of Green Gables), reviews of mega-peers (Stephen King, Hilary Mantel, Doris Lessing and Rachel Carson) and finally articles that circle around all the above: Atwood on quarantine, Atwood on science and science fiction, Atwood on beauty, Atwood on the environment, Atwood on birdwatching with her husband.

It comes as little surprise to discover that all these Atwoods are self-assured writers: fluent but unflashy, funny and unassumingly emotional. This is partly the result of practice; as she also records in her introduction, Atwood has always found it hard to say no to interesting assignments.

But it is also a consequence of being Margaret Atwood. How many writers would begin a prestigious lecture (at Ottawa’s Carleton University) by highlighting the fact she is the first woman to deliver it, and then disperse (and possibly increase) any embarrassment by cracking cutting jokes at her own expense.

First, she is too short to be threatening (“and apart from Napoleon, what short person has ever been threatening?”), and second she is an icon, “and once you’re an icon you’re practically dead, and all you have to do is stand very still in parks, turning to bronze while pigeons and others perch on your shoulders and defecate on your head”. Take that.

Atwood has taken some trouble to put the 50 or so pieces into some sort of order. There is the title, which, she explains, is suggestive of urgency, whether about democracy, escalating inequality (of wealth and race) or the environment. The “essays” themselves are further “arranged” into five sections with somewhat tremulous titles, including Art is Our Nature, and Thought and Memory.

Literary ambition in 1960s Canada was something “about which you would of course feel defensive and ashamed, because art was not something a grown-up morally credible person would fool around with”.

Seeking less familiar terrain, one could turn to Somebody’s Daughter, a report about a camp that forges bonds between the Inuit women of Nunavut, in the Canadian Arctic, by teaching them traditional crafts and literacy skills. Atwood encounters a polar bear, eats caribou and uses writing to teach about feminism.

All of this coalesces in a short foreword to her husband’s bestselling The Bedside Book of Birds (2005). Atwood sketches their relationship through a shared love of birdwatching: how a childhood passion she had taken for granted was renewed by Gibson’s enthusiasm; how this inspired him to collect bird myths and support various conservation activities; and finally how birds sustained them both during the last year of Gibson’s life, when vascular dementia had robbed him of almost everything else.

“Our backyard feeder and our birdbath were attracting only sparrows and robins and grackles and the occasional pigeon, but he didn’t care: every bird was worthy of attention.”

One could say something similar about certain pieces in this excellent collection.