No money, no English: a Chinese family in Canada rose from the bottom and now own a fruit and veg empire

- Leung Kin-wah’s family left Guangzhou for Vancouver in 1981 with little money, not much English but a desire to work hard. Now, they own a fruit and veg empire

- This year, Kin’s Farm Market celebrates its 40th anniversary. Leung, who helped his parents start the company up, talks about its beginnings and its future

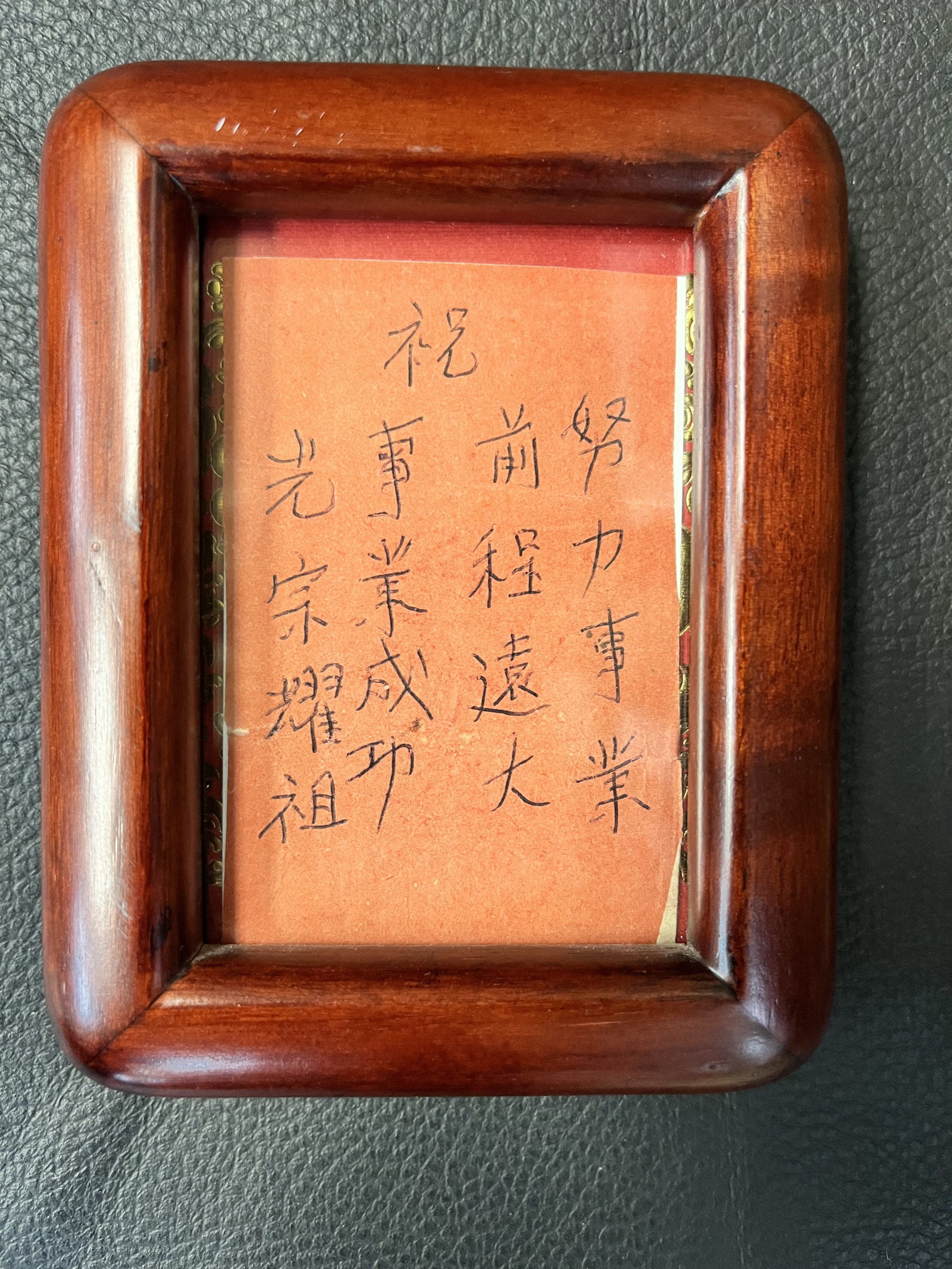

Back in 1981, when Leung Kin-wah was packing up to leave Guangzhou with his family and migrate to Vancouver, his 80-year-old paternal grandmother handed him a lai see packet.

“You’re going to Canada, so there is the possibility I won’t see you again,” she told her then 21-year-old oldest grandson. “Don’t open this now, only after you arrive in Canada.”

“It was so special, better than giving money,” he says of her words of encouragement.

Leung has since framed the piece of paper and remembers these words every day as he works at the headquarters of the family business, Kin’s Farm Market, which recently celebrated its 40th anniversary.

Four decades ago, the family of five, including Leung’s younger brother, Kin-hun, and older sister, Kin-fun, began their new lives in Canada, with only meagre savings, and not much English.

This whisky is made from rice. In Canada. By a Chinese immigrant

After two years, Leung recalls, a friend took his family to a tourist attraction called Granville Island, where they saw vendors doing brisk business selling fresh fruit and vegetables on tables they rented out daily.

“New immigrants wanted to get into business, but how?” says Leung of that time. The family decided to give it a try, despite knowing nothing about retail, let alone the fresh-produce business. Back in Guangzhou, Leung’s parents had worked in a state-owned bus company, his father in human resources, his mother in bookkeeping.

“We only knew about gai lan and bak choi, we didn’t know what raspberries and strawberries were,” he says. But when they saw people buying these berries, the family found farmers to source them from, along with other popular produce such as lettuce.

People liked buying their produce because it was fresh, but business slowed down significantly during the winter. Granville Island is located right by the water, and when business was slow, Leung would set crab traps, reasoning that if they didn’t sell much produce, at least his family could eat crab.

However, they could not watch both the traps and the stall at the same time, and the traps were stolen. Adding to their dismay, they discovered that other stalls were making 10 times more daily revenue than they did.

The Leungs realised they had to step up their customer service and use their broken English to persuade people to buy from them.

“We introduced the produce to them, told them how to prepare it, or gave fruits to the children and chatted with their parents,” says Leung.

They called it ‘Humiliation Day’: the Canadian law that split Chinese families

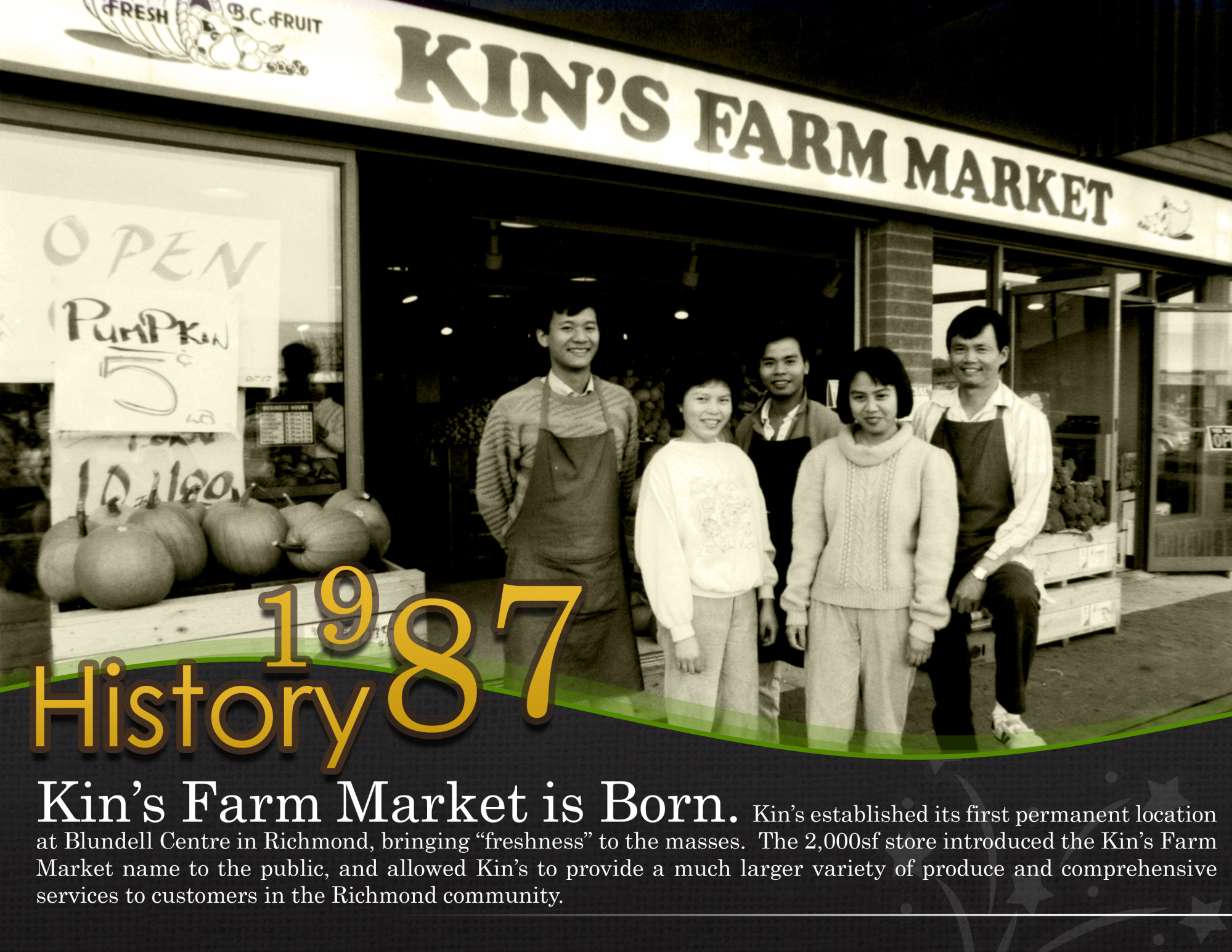

Leung’s wife, Queenie Chu, adds: “At the time paper bags were expensive and we got a lot of plastic bags for free, so we helped people bag their other purchases as an extra service.” Chu started working as a cashier at Kin’s in 1987 and the couple were married six years later.

It was this philosophy of treating customers like friends that helped the family build its business to the point where they could open their first bricks-and-mortar shop, in Richmond in 1987.

“Each farm’s growing season is different, but usually the beginning and end of the season don’t have the best produce,” he says. “It’s the period in the middle when the produce is the best, so I only buy it then. That’s why I go to different farms to source the same produce because I need to give the best to customers.”

In 1990, the family opened their second store, in Ladner, which was double the size of the Richmond shop. Following customers’ suggestions, the Leungs tried selling dry goods, such as sauces and newspapers. But after a few months it became clear that no one was buying these items and they were just taking up space. The Leungs decided to once again focus on their strength – fresh produce.

“We welcome all people to come here to shop,” he says. “We have done so well with the local Canadian population and they have accepted us. We can open shops anywhere.”

They saw their limitations in 2007, however, when they expanded on the east coast with two stores in Ontario, an hour’s drive from Toronto. Finding it difficult to manage the businesses from afar, they closed them after about three years.

Leung’s stepson, Victor Lau, is the chief operating officer and third generation of Kin’s Farm Market. In high school, Lau started stocking produce and learning bookkeeping. After graduating from university with a business degree, he worked in merchandising and now focuses on buying, distribution and marketing.

During a tour of their warehouse, we spot supersized button mushrooms, bright-red hothouse tomatoes, deep purple plums, sweet-smelling peaches and several varieties of grapes including the coronation, which starts sweet and has a slightly tart finish.

Kin’s buys as much produce locally as possible, but in the off-season they source from 45 countries, including the United States, Mexico and as far away as Israel, Japan and the Netherlands.

Today, Kin’s Farm Market has 23 stores and Leung says they are keen to expand further.

“I believe every neighbourhood needs fresh fruits and vegetables,” he says, explaining the manifesto that supports their motto: “To inspire a better quality of life in our communities.”