How baijiu, China’s ‘white spirit’, stopped being uncool thanks to hip cocktail bars that are making it part of a new ‘drinking language’

- China’s national drink, baijiu had fallen out of favour with Chinese youth, but a renaissance is happening, thanks to cool bars that specialise in the spirit

- We talk to a bar owner whose Instagrammable cocktails are making youngsters ‘excited to learn about baijiu’, and look at how the drink’s marketing is evolving

In the 2021 Chengdu International Spirits Competition, Bastien Ciocca – co-founder of award-winning cocktail bars Hope & Sesame and SanYou, in Guangzhou, southern China – was one of two foreigners on the baijiu-tasting panel.

Nobody paid him any attention, not even when he wrote tasting notes that were similar to those penned by the master distiller of Luzhou Laojiao, a baijiu brand that dates back to 1573 during the Ming dynasty.

Heads only turned towards this perceived token foreigner after the audience learned that his bar SanYou, now with a branch in Shenzhen, is one of the few baijiu cocktail bars in the country.

Made mainly with sorghum, baijiu is a distilled spirit that’s fermented in urns or mud vats that may have been around for centuries, contributing to its sought-after vim.

Although infusions are popular, the flavours in baijiu – unlike whisky and gin – come from the spirit itself. Four main aroma categories were born in 1959 – light, rice, strong and sauce.

Baijiu’s ubiquity within the country and among the Chinese diaspora has placed it among the world’s bestselling spirits, with the top brand – Kweichow Moutai – charging more than US$5,700 for its finest bottle. As of February 2024, its market capitalisation is nearly seven times greater than that of French alcohol giant Pernod Ricard.

Yet most non-Asians have never heard of baijiu. And even if they have, its 50 per cent or higher alcoholic content limits its appeal, and its vermilion packaging is seen as a barometer not of patriotism but of corruption and as uncool, even among Chinese youth.

Ciocca has been pushing century-old baijiu brands onto the cool train. At SanYou, whole bottles are never sold – unlike how the older generation buy it – and visitors are greeted with a box that reveals towelettes, snacks and a low-alcohol welcome drink all laced with baijiu, which he calls a conversation starter.

“More often than not, our customers at SanYou outright admit they don’t like baijiu and that they only came because they liked Hope & Sesame,” Ciocca says, adding that most of his clientele are local twenty-somethings.

“This box is like a fine-dining experience but for drinks; it tells a story in a fun way that invites them to stay beyond taking a picture of the cocktail and leaving. They are excited to learn about baijiu.”

The 400 baijiu in SanYou’s collection are used mostly as enhancers for Instagrammable cocktails – married with tortoise jelly, infused with pumpkin seed pastry or washed with chicken fat (the last one whimsically served in poultry-shaped apparatus).

Ciocca says that since SanYou launched in 2020, he has seen more baijiu cocktail bars opening around the world, such as Laowai, in Vancouver, Canada.

He believes that baijiu’s relative obscurity outside China stems from poor marketing by brands that have been spoiled with remarkable demand for the past 30 years.

They know a threat is coming, but real change, Ciocca predicts, won’t happen for at least a decade.

Baijiu is not more difficult to understand than, let’s say, mescal. We just need more people to taste it and appreciate it

That change can mean something as minute as more informative labelling, or bigger strokes such as training brand ambassadors so that bartenders and consumers can better appreciate their product.

This lack of outreach, adds Ciocca, also has to do with the nascency of China’s cocktail scene.

“China is a big country, and change comes gradually. Sure, baijiu isn’t seen as much in big banquets, but small gatherings still take place; so the industry isn’t feeling any real need to be different,” he says, adding that brands’ top brass – mainly traditional Chinese businessmen – just can’t grasp what it means to be cool.

Zachary Chan Tin-ying, co-founder and director of HK Liquor Store, is happy to get any marketing direction from the baijiu brands on his shelves.

The more aggressive ones, such as Luzhou Laojiao, which hosted 110 events last year, including sold-out tastings at Chan’s stores, saw better sales than staples such as Kweichow Moutai. Other, more complacent ones remain in their shadow.

“The only way for people to understand baijiu is to taste it, but still this is only the first step,” Chan says, adding that the industry is struggling to find attractive descriptors like the ones prominent on Western spirits; instead, the brands fall back on long-winded backstories that make them almost indistinguishable from one another.

Simple pleasures: how Asia’s wine bars are shedding their stuffy image

“The baijiu education system in China is relatively new; they’ve been busy making it for so long but never had to talk about it,” he says. “They talk about their history and how their great-grandparents started making it. That’s nice – now tell me why I should drink you over the 600 other brands out there that have the same style.”

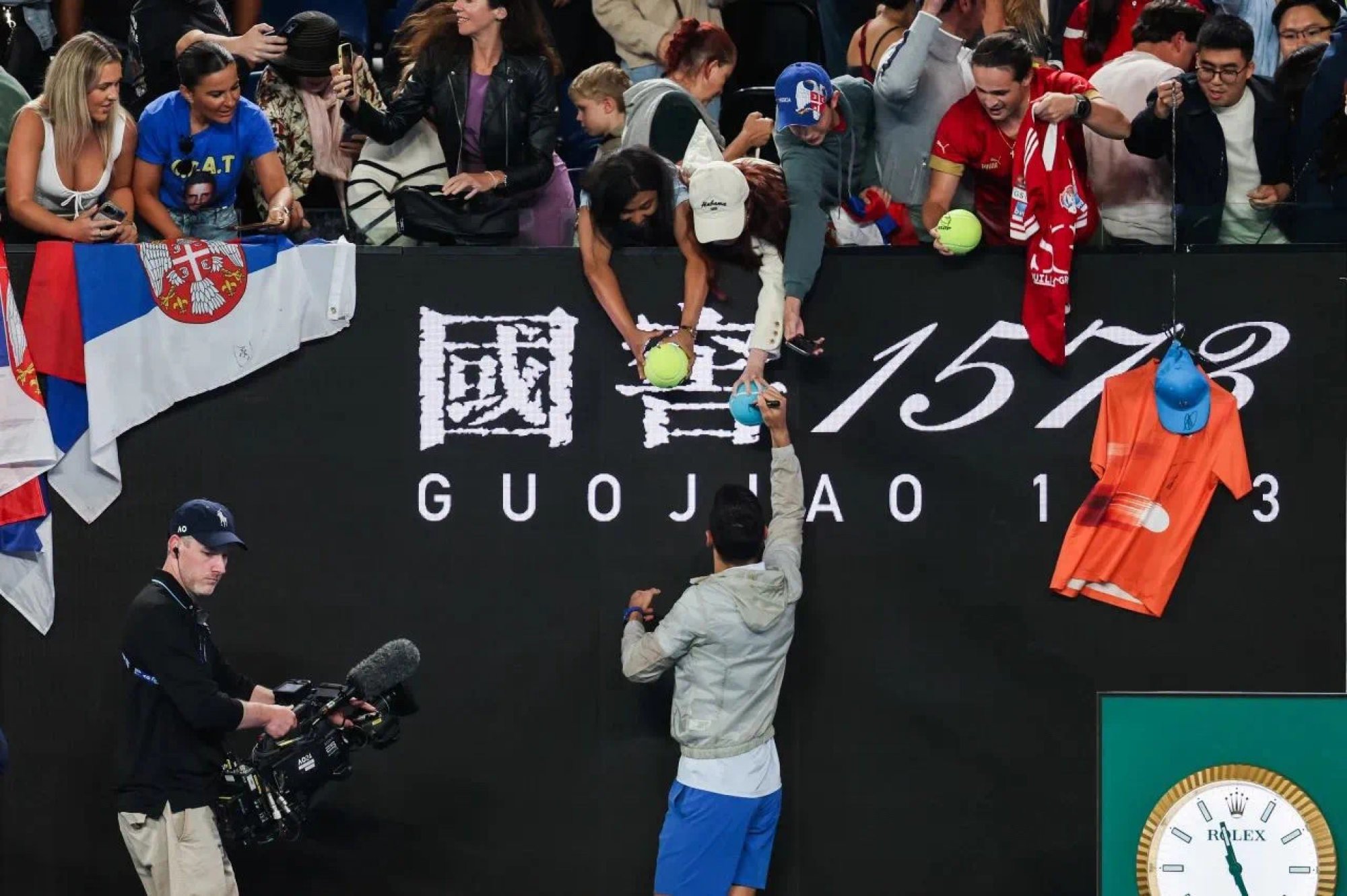

Brands are, however, trying. Jiangxiaobai – a light-aroma baijiu from Chongqing, in Sichuan province – has been sponsoring music festivals, dance competitions and street art. Luzhou Laojiao, meanwhile, has been backing mega events such as the Australian Open and the Olympics.

Lucy Siu Lu-lu, senior regional sales manager for Hong Kong, Macau and travel retail for Luzhou Laojiao International Development (HK), agrees that the baijiu industry needs to react to a changing audience.

She takes pride in the brand’s many bar and restaurant collaborations, mainly done with its entry-level line, Ming River, designed to be used in cocktails and for an overseas market, which is evident in its lower alcohol content and, of course, the English name.

“Five years ago, we started doing travel retail; progress is slow, but now we are in the duty-free spaces in Japan and South Africa,” she says. “We even have our own office in the United States.”

Back at SanYou, Ciocca is reaching out to Kweichow Moutai, whose recent presence in ice cream, coffee and even skincare has shown up on the radars of the cool crowd. He knows that other brands will follow.