What street names say about Hong Kong’s maritime past

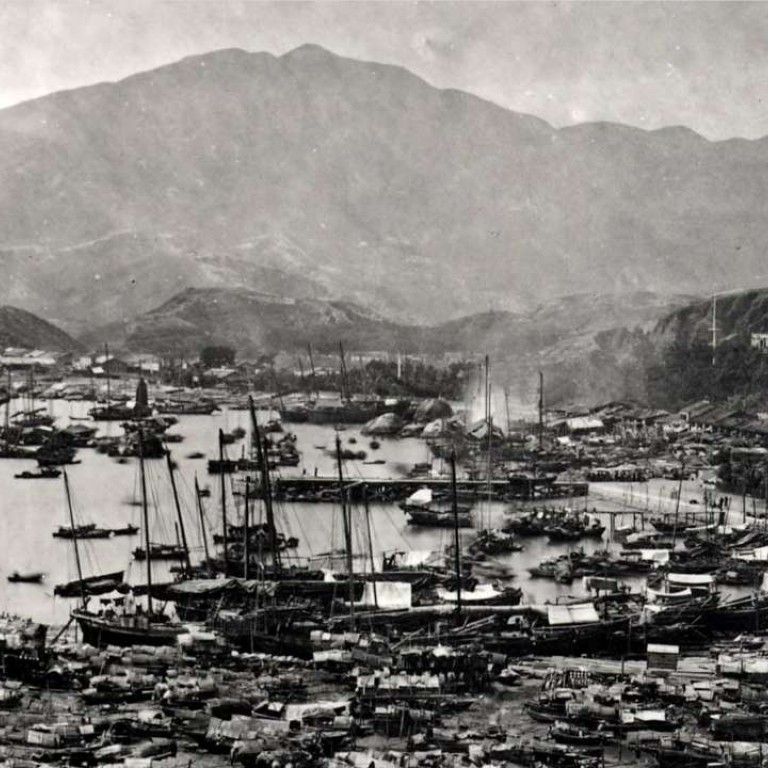

Colonial bias has left much of the city’s Chinese maritime heritage off the map, a historian writes

For no good reason, apart from a lifelong obsession with ships, the sea, seafarers and my Hong Kong home, I have found myself wondering what our street names can tell us about the city’s maritime story. So recently I started conducting a little exercise in the arcane study of street names, “hodonymy” to its fans, to find out whether those with a maritime link – by subject, date or location – would reveal any interesting patterns.

So far, I’ve come up with 114 street names, deliberately omitting those related to seashore topography – Headland Road, Deep Water Bay Road, Beach Road and the like. I have stuck with Hong Kong’s day-to-day maritime business, the people who did the work, the things they worked on or with, and the seaports with which Hong Kong has traded, such as Amoy, Newchwang, Foochow and Ningpo. As a result of my limited Chinese, and some doubts about what I should include, this is a work in progress.

Considering Hong Kong is one of the world’s great ports, street names with maritime connections are remarkably few – no more than 10 per cent of the total. But that is enough, when loaded into a database and tested for patterns, to add to what we know of Hong Kong’s maritime story, to reflect the biases of colonial officials who chose the names and the resolutely unmaritime – even anti-maritime – cultural proclivities of Hong Kong’s Chinese population.

Take location, for example; 70 per cent of the names on my list are on Hong Kong Island. Of those, the overwhelming majority are on the north side, with almost two-thirds located between Causeway Bay and Kennedy Town.

Combined with an analysis of when the roads got their names, divided into crude 30- to 40-year periods (some of the dating is very ballpark), the street names confirm Hong Kong’s development as a port began on the island and remained focused there until the early 20th century. They also show that the city’s emergence as a major global port got off to a fairly slow start, accelerated through the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th, eased back, and then experienced another surge from 1975, the era of containerisation.

Plotted on a map, the street names show how Hong Kong’s port has moved, as reclamation left the old working waterfronts inland. Names connected with shipyards – such as Sands, Fenwick and Ship streets – indicate there were once shipyards on the waterfronts of Kennedy Town and Wan Chai. Other street names in Kowloon and Quarry Bay – such as Dock and Bailey streets and Shipyard Lane – suggest the noisy, messy, land-hungry maritime businesses shut up shop or moved as ships got bigger, more complex and more expensive.

In east Causeway Bay and North Point, Yacht Street and Boat Street mark the sites of the first Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club and well-known yacht builder Ah King Shipyard, respectively, and are both now far from the sea.

When Kowloon began to supplant Hong Kong Island as the focus of deep-water berthing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and as settlement there expanded, new streets were named after the ports with which Hong Kong traded, including Saigon, Malacca, Tientsin and Shanghai.

The broad categories of names are interesting, too. Not surprisingly, the gritty realities of port life lead the field, accounting for 41 per cent of our 114 street names, including Ferry Street, Pier Road, Shek Chan (“stone godown”) Lane, Wharf Road, Shipyard Lane, Boat Street, Anchor Street and so on.

Another quarter of our sample is named for maritime people and dominated by Royal Navy worthies: Belcher’s, Bremer (ignoring its shoddy, 1949 misspelling “Braemar”), Cochrane, Collinson, Drake, Gage, Harcourt, Kellett, Nelson, Parker, Rodney and Seymour. Next come maritime business luminaries – including Thomas Sutherland, Douglas Lapraik, William Bailey and John Finnie – and just two representatives from the maritime side of government, William Pedder and Robert Rumsey. Curiously, Hong Kong’s longest-serving harbourmaster, Henry George Thomsett (1860-1888), had no street named in his honour, which tells us something about the status of the harbour in bureaucratic minds.

After people – though some way behind, at 14 per cent – come streets named for Chinese and Southeast Asian ports.

Then come names associated with shipping and other maritime-related organisations, although almost always allusively, such as Tit Hong Lane, meaning “iron company”, or P&O; Oil Street, after Socony-Vacuum Oil; and Shell Street, for Shell Oil.

Other names in this category reflect traditional Chinese maritime life, such as Ham Yu (“salted fish”) Street; seafarers’ gods (Tin Hau Temple Road); as well as Hong Kong’s pre-colonial years. Ma Tau Kok (“pier point”) Road and its variants probably refer to a long pier near the old Kowloon Walled City (the rather oddly translated Lung Tsun Stone Bridge), dating to 1873, the remains of which were unearthed in 2008.

HONG KONG’S MARITIME STREET names allude to a resolutely Western, colonial, pre-war world. The people commemorated are exclusively Western and mainly from the first century or so of Hong Kong’s colonial era. The same is true of the shipping interests they represent. Douglas Steamship Co is memorialised by Douglas Lane. Hongkong and Whampoa Dock gave rise to Dock Street, and Gillies Avenue was named for David Gillies, general manager of the dockyard. Royal Interocean Lines, a Dutch company that operated a regular passenger ship service between Java and China, is remembered by Java Road. Subtler but just as biased, the Chinese renderings of the names are almost always reductively phonetic – such as An Ka Kai for Anchor Street, not Mau Kai or Ding Kai – obscuring the streets’ maritime connection for Chinese speakers and readers.

As a result, our street names give a misleading impression of Hong Kong’s maritime story. So we need to feed into our picture the names we could have expected but that are missing. These include the people and businesses in early Hong Kong’s large and busy Chinese maritime world, whose names appear nowhere, as well as maritime activities that were never reflected in the names of the streets where they took place. Others did once appear in street names but have been eradicated by development or bureaucratic whim.

So there is no road in Sheung Wan named Nam Pak Hong after the South North Company, a pre-1851 sea-trade organisation that formed one of Hong Kong’s oldest and most important Chinese shipping concerns. Neither is there a street named for Tam Achoy, one of modern Hong Kong’s first traditional “elders” and a co-founder of the Man Mo Temple, whose maritime interests included leasing a pier to the Hongkong, Canton & Macau Steam Boat Co. Above all, there is no street name that references the burgeoning emigrant trade about which historian Elizabeth Sinn has written so eloquently in her book, Pacific Crossing (2012.) Also invisible are Ko Mun-wah (or Gao Manhua), a founding director of the Tung Wah Hospital, and his business, Yuen Fat Hong, established in 1843 as part of Nam Pak Hong, which he took over and made successful.

Hong Kong’s first Chinese owner of a modern steam fleet, Kwok Acheong, the one-time comprador of P&O and another co-founder of Tung Wah Hospital, is similarly ignored. By 1876, he owned 13 steamships and, when he died in 1880, was Hong Kong’s third greatest ratepayer.

No street in Western or Kennedy Town marks China’s first modern shipping company, China Merchants, founded in 1872 and active in Hong Kong as of the 1880s. Merchants’ Wharf Pier is close to where its 19th-century forerunner was, but no street name reflects this near 140-year maritime presence.

Other than Anchor Street, the paraphernalia of shipping – cargo, chandlery and so forth – is almost equally invisible. There is no Coal Street, for example, even though Hong Kong was importing 944,000 tonnes annually by the early 1900s.

Ropewalks – the long, straight narrow lanes in which strands were laid before being twisted into rope – and their ancillaries get no direct mention, although Hong Kong had several over the years. Today, nothing recalls the open space in Ap Lei Chau once called Ta Lam Lo, which translates roughly as “ropewalk”, and which was associated with rope making as late as the 1960s. Also ignored are Wong Ping and the ropewalk he owned at the western end of the long-gone Lower Bazaar, in Sheung Wan.

The only street name that might allude to rope making – and there are grounds for doubt – lies further west, in Forbes Street, where the Kennedy Town Rope Works was founded in 1895 by Russell & Co (headed by Robert Bennet Forbes) and grew into a major international manufacturer and exporter, the now-defunct Hong Kong Rope Manufacturing Co.

Other absences from the story are names that have disappeared along with the world they belonged to. In Tai Kok Tsui, any echo of the Cosmopolitan Dockyard and the many boatyards that built and repaired small craft in the area was lost when Ship Lane and Junk Street disappeared. The same is true of Navy Street, in Tsim Sha Tsui, which once marked the Royal Navy’s Kowloon Naval Yard, with its torpedo camber and coaling depot.

Lamont’s Lane, in Causeway Bay, once recalled shipbuilder John Lamont. He built the first Western-style ship in Hong Kong, the little schooner Celestial, launched in 1843; Hong Kong’s first steamship, the Queen, launched in 1853; and the Aberdeen dry docks, opening Lamont Dock in 1859. Once a short, private alley off Fuk Hing Lane, which runs from Jardine’s Bazaar to Jardine’s Crescent, Lamont’s Lane has been zapped by development.

Long gone, too, are Hong Kong’s “bunds”, echoes of Shanghai’s famous waterfront boulevard. The South Bund and West Bund used to run along the seashore near the Hongkong & Kowloon Wharf & Godown Co and the Kowloon Naval Yard, close to modern Canton Road. Also gone – in favour of the names of landlubber colonial government worthies – are those of the first waterfront thoroughfares, The Praya (Hoi Pong) and its extensions the Western Praya/Praya West (now Des Voeux Road) and the Eastern Praya/Praya East (Johnston Road). Only the Kennedy Town Praya and Kennedy Town New Praya survive.

BUT IT ISN’T ALL LOSS. Since the 1980s, names referencing modern maritime Hong Kong have appeared, and have done so more even-handedly than in the past. We now have World Wide Lane (named for Sir Y. K. Pao’s post-war shipping company), Container Port Road South, near the current container port in Kwai Chung, and Yue Shi Cheung (“fish market”) Road, in Aberdeen. There have even been thoughtful nods to a forgotten past, such as Kong Sin Wan Road, in Cyberport, which commemorates Hong Kong’s first submarine cable, landed in 1872 by the Eastern Extension Telegraph Co in what became Telegraph Bay (Kong Sin Wan).

There are borderline cases, too, like the housing estates in Shek Pai Wan whose names all begin with Yu (“fish”) to reflect Aberdeen’s fishing past. Those were named in the late 20th century, but an earlier example can be found in Shau Kei Wan, where part of the bay was reclaimed in the 1920s and five roads were built whose names all begin with Hoi (“sea”).

Other street names are faint echoes of obscure maritime historical “relics”. I have two favourites: Tin Lok Lane and Haven Street.

Tin Lok Lane is an extension of Morrison Hill Road, between Wan Chai Road and Hennessy Road, and a last echo of Observation Point, the starting datum for Edward Belcher’s pioneering 1841 survey of Hong Kong waters. Originally a small promontory jutting out into Victoria Harbour, later called Point Albert, after Queen Victoria’s consort, Observation Point was quickly swallowed by reclamation. It appears in pre-war gazetteers as Observation Place, or Tin Lok Li in Chinese.

A short alley off Leighton Road, Haven Street is a private road first named in 1931 that recalls an earlier time, when Causeway Bay ran all the way up to Tung Lo Wan Road and a little tidal gully in its southwest corner provided a haven for small craft. It’s nice to think the memory has endured.

Some “maybe maritime” names throw up interesting puzzles too. Are Minden Row, Minden Avenue and Blenheim Avenue named after Royal Navy ships that served in Hong Kong? Or are they the names of prized battle honours (Blenheim 1704, Minden 1759) of British Army regiments that occupied land nearby during their time in Hong Kong?

Should we count punning derivatives, such as Tim Wa Avenue and Tim Mei Avenue, both clearly plays on “Tamar” – the name of the ship that served as the Royal Navy base in Hong Kong, and later the name of its shore station – as maritime in origin? What about maritime-sounding names such as Sam Pan Street and Schooner Street? We know they were not directly related to sampans on the seawall at the end of the road or a newly built schooner on the slipway of a nearby shipyard because, by the time they appear in the early 20th century, the sea was at least two blocks away.

Hong Kong street names are a wonderful entry point to the stories of the people, practices, paraphernalia and places that created the city’s maritime history, both in what they tell us directly and in where they are notably silent.

NAME CHECKING

In an attempt to be as comprehensive as possible, I have revisited the first street-name index, from the late 19th century. Before that the only recourse is maps, and the map record before the grand resurvey in 1900-04 is aleatory.

There is some evidence that not all paths, alleys and so forth had official names until quite late on (the 1870s-80s or later), though by 1860 almost all streets and roads did. There is no record of unofficial names or colloquial Cantonese names, except where these have been recorded or remembered, and there is no evidence except anecdote of how far back these may go. We can be fairly confident we have all the early maritime names that subsequently gained official recognition, which have been cross-checked against annual Public Works Department reports.

Cross-checking has also been carried out against earliest known references in all readily available government documents and, where possible, newspapers. After the jury lists were published (from 1854), the main street names where jurors lived were mentioned. The primary check, though, usually involved some government notice about night soil or rubbish collection points, rickshaw stands, land sales and so on. Wide date brackets are used because often only a first reference date is available, with no clarity of when before that date a street was named.

For those names that do not exist, I have gone as deeply as scant resources and luck will allow. We can be sure that some will have been missed, and equally sure there will have been names that never surfaced in any record, so stumbling on one would be by pure chance. Even if stumbled upon, one would have no clue how widely such a name was in currency or for how long.

By definition, therefore, not only is there no complete list of all the names there ever were, but no such list can be compiled using currently available sources.