Who is getting the Chinese vote in the French presidential election

As the presidential election looms in France, the country’s Chinese community is coming together to make its voice heard. So who will they be rooting for on Sunday?

For the first time in the history of France, a significant number of French Asians are prepared to make their voice heard in a presidential election.

Ahead of the first of a probable two rounds of voting, which takes place on April 23, Post Magazine talked to some French Asian voters to see which of the 11 candidates appeal to them.

We meet Li Hong in Le Bistrot de Pekin, an elegant restaurant a few hundred metres from the Chinese embassy in the chic Parisian neighbourhood of the Champs-Elysées.

“I came here, I saw the beauty of the country – Paris, the Côte d’Azur – and suddenly I had the feeling I had found my second home, that France was also my country,” says the sprightly 60-year-old from Beijing, who is sporting a flashy red-leather jacket over a pink jumper.

Li arrived in France in the late 1980s, working as an assistant in a maritime logistics company while studying for a master’s degree. A few years later, she opened her own company, importing Chinese textiles specifically designed for firemen and laboratory workers. In recent years, she says, she has seen the French economic landscape become more challenging for small businesses.

Her preferred candidate in the election is François Fillon, the embodiment of the conservative establishment, who is from a staunchly Catholic background. His manifesto is based on tax and public-sector cuts and the tightening of immigration rules, and he has taken a traditional stance on gay and reproductive rights.

“Only he can save France,” says Li.

The fact Fillon is under investigation for the embezzlement of public funds – specifically for paying family members for fake parliamentary jobs – is of no relevance to Li.

“All députés [MPs] are pulling the same trick,” says Li. “It is just a conspiracy to make him fall so he cannot win the election. Plus, if you look at the amount of embezzled money [a few hundred thousand euros], it is really peanuts compared with the level of corruption we are used to in China.”

About 19 per cent of voters still think he is the best candidate for president.

Sitting next to Li, her husband, sixty-something Li Lingchung also likes Fillon, although he could be tempted to support Emmanuel Macron, the young centre-left ex-banker who is a surprise second favourite in recent polls (with about 22 per cent support), just behind the ultranationalist Marine Le Pen (23 per cent). His pro-Europe, liberal stance and apparent ability to agree with everybody have won him many supporters but his age (39) and lack of experience make him less credible to others.

“I don’t think he will be able to make the right alliances in order to govern,” says Li Lingchung.

For years we have been systematically targeted. About 10 assaults a day are happening against the Chinese community in Belleville

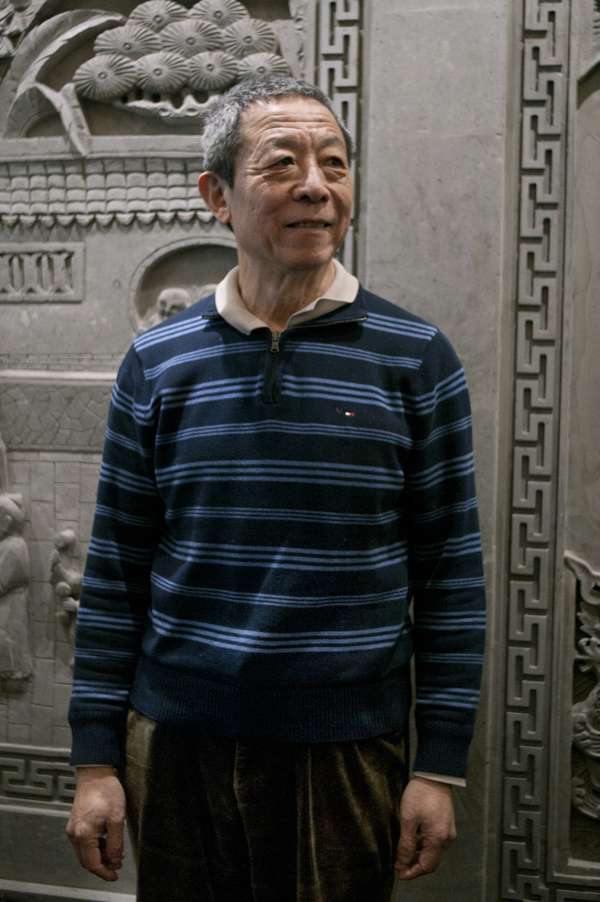

Another name comes from the Lis’ former French-language teacher, Professor Liu Yazhong, president of the Association of Former Chinese Students in France, who has joined us. Like most Chinese intellectuals who came to France in the 1980s, he is left-leaning, and this time he is backing Jean-Luc Mélenchon, a hardline leftist whose manifesto includes the renegotiation of European treaties, increasing the minimum wage and implementing a new constitution.

It is estimated there are between one million and 1.5 million first- and second-generation French Asians, although it is difficult to ascertain exact figures, as France does not allow statistics gatherers to inquire about ethnicity. Once someone acquires French citizenship (and thereby the right to vote) he or she disappears from immigration tallies.

It is known, however, that the Chinese form the largest Asian ethnic group in France. And their number has been bolstered by several waves of immigration.

First came the Chaozhou (also called Teochew) refugees from Indochina: Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.

“At least 60 per cent of [refugees from Indochina] were Chinese, and only 40 per cent actually were ethnically Cambodian, Laotian or Vietnamese,” says Liu.

These families had left China over several generations to settle in Southeast Asia. As they tended to represent the elite in the countries in which they had settled, they were among the first targeted when communist governments came into power in the region in the 1970s.

When they arrived from their war-torn countries, many Teochew settled in the south of Paris, in the 13th arrondissement, known since then as Le Quartier Chinois (“Chinatown”). They worked in supermarkets and opened restaurants or grocery stores. More than 120,000 refugees from Southeast Asia were admitted without political opposition; that’s four times the number of Syrian refugees France has reluctantly agreed to take in recently, creating a heated debate in parliament.

Undoubtedly, in the confusion of the ’70s and ’80s, an unquantifiable but significant wave of people from mainland China also migrated to France.

Generally speaking, these ex-refugees are considered supporters of the left-leaning parties. First, because politicians from the left are known to be more open to immigration and many got their French citizenship under the socialist government of François Mitterrand (1981-1995). Furthermore, because of the rough conditions they endured on arrival, “their economic development was quite slow,” says Liu, and thus they were not in a position to take advantage of the economic rise of China, as later arrivals have done. They therefore tend to benefit more from the social policies offered by the left.

Our parents came from countries where there wasn’t any freedom to think for oneself, let alone vote

The second main group of Chinese arrivals came from the Wenzhou region of Zhejiang province: the “Wen”, as they are known, as if they were an ethnic group in their own right. Even though they came to France en masse only recently, the initial batch of men from Wenzhou arrived during the first world war.

Similar to the Chinese Labour Corps recruited by the British government, France enlisted an estimated 40,000 Chinese workers to help in French factories and in support roles behind the front line. Thousands died at the front or from the Spanish flu, and most of those who survived returned to China, but about 3,000, mostly from Wenzhou, remained. They opened small businesses and many of those who prospered would approach the end of their lives without an heir. According to immigration studies, distant relatives

were summoned to inherit small fortunes and continue the businesses in France.

“In the beginning of the ’80s, I met several people in a [Chinese] airport; they were going to France to meet an old relative they had never met and become his heir,” says Liu.

The big wave from Wenzhou came later, though, in the ’90s. And on the whole they benefited from the economic rise of China. They bought small shops selling textiles, leather and jewellery, and then cafés and tobacconists; they settled in Belleville, a former working-class district where rents were still affordable and where many Jews from North Africa had settled in the ’60s. More recently, Belleville has seen the arrival of families and single women from northeastern China, not all of whom have arrived legally.

The communities have co-existed peacefully and today, with its Asian bazaars and hipster cafés, Belleville is one of the trendiest neighbourhoods of the French capital.

Until recently, the Wen had a reputation for being uninterested in national politics.

“My family could not care less about politics,” says Mélanie Ren, the very French daughter of the Wenzhou owners of a Belleville leather shop. “Here or anywhere else, to be honest. We never talk about it.”

But things are changing. The second generation is now old enough to vote, and to convince their elders to do the same. Like many other business owners, the Wen could be attracted by the promise of tax cuts and bureaucratic simplifications made by the right.

“A lot of Wenzhou people will vote for Fillon,” predicts the Chinese owner of a grocery store in rue de Belleville.

A tendency towards non-involvement in French politics has been common to all Asian groups, the language barrier and the complexity of an electoral system that can put forward 11 candidates having played their parts.

“Our parents came from countries where there wasn’t any freedom to think for oneself, let alone vote,” says accountant Jacques Hua, the son of Teochews from Cambodia.

To encourage second-generation Asians to participate in this election, Hua, together with director Hélène Lam Trong, who is of Vietnamese descent, have made a short video aimed at a young audience on social media. The video quickly attracted a million online views.

“The idea was to give young Asians of France a sense of pride and belonging,” Hua says. “Most of us still have to justify our ‘Frenchness’ on a daily basis.” And that struggle is not helped by the prevalence of anti-Asian racism in France.

“There is a kind of socially accepted racism against Asians, because it’s considered funny,” explains Frederic Chau, a comedian of Cambodian-Chinese descent who has popularised the Chinese accent in his shows and become the face of young East Asians. While open racism against Arabs and blacks is considered unacceptable, jokes poking fun at Chinese speech, food and clothing are still commonplace among French youngsters.

“Second generations do not want their children to be exposed to the same kind of racist taunting at school that they had to face,” says Lam Trong, explaining another key driver of political engagement. In the past 10 years, about 100 Asian associations have been created, all with more or less the same goal: to foster a voice, visibility and empowerment for a group that is still subject to vilification and worse.

There is a kind of socially accepted racism against Asians, because it’s considered funny

Speaking in Pho 168, a Vietnamese restaurant in Belleville run by Wen, Shi says he arrived as an illegal immigrant in the back of a truck, with many others, in 1999.

“My first memory of France was a moustache,” he smiles. “That belonged to the policeman who opened the door of the truck; a nice guy, who probably saved my life.”

Shi was aiming to get to Britain; a few months later, 58 young Chinese were found dead in the back of a lorry in Dover, after having sailed from Belgium.

Quick to learn the language, Shi worked as a translator for the police, in the process learning of the plight of Chinese shop owners who were being hounded daily by gangs of youths from neighbouring blocks.

“We started to talk among ourselves and to the police, telling them that the situation could not last,” he says.

After years of silence, the first Chinese protests took place in June 2010. As a result, a special police unit, the Brigade Spécialisée de Terrain, was created and deployed in Belleville.

“The situation is much better than it was in 2010,” says Shi.

Last year, French Chinese mobilised again following the death of Zhang Chaolin, a 49-year-old tailor who was beaten by three young muggers in northern Paris, in August. For the first time, Asian citizens were seen occupying the Place de La République, where all major protests take place, waving French flags and asking the government to protect them. “These protests are part of a democratic learning process,” says Lam Trong.

Last month, Liu Shaoyo, a father of five, was shot dead in his home by a policeman after a neighbour reported a disturbance. Although his death had little to do with his ethnicity, the ensuing demands for justice for his family once again put the Chinese in the spotlight, giving candidates such as Macron the opportunity to shake hands with leaders of the community.

Some politicians hadn’t waited for a death. Over the past year, representatives of the Front National, the populist and ultranationalist party headed by Le Pen, “came regularly to visit and talk with members of the community”, says Hua. The question of safety being so crucial for the Chinese, the Front National’s proposals on harsher punishment for criminals and an increased police budget have a particular appeal. The nationalist stance against Muslims, accused by some of being responsible for the insecurity in the country, is also attractive to some Asians.

Nevertheless, the Front National remains a hard sell where most Asians are concerned.

“It would not make much sense for children of immigrants to vote against their own rights, like the right of the birthplace,” says Ren.

Says Hua: “Maybe it is too early for them to vote for the Front National, but in 10, 20 years [...] who knows? If their safety situation does not improve, many could be tempted.”

Liu continues that thought, “Especially if Marion Maréchal-Le Pen [the niece of the Front National’s current leader] takes the reins. She is perceived as less aggressive than her aunt, and her more soft-spoken personality could appeal to the community.”

And Li Hong? “If the second round of the election is between Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, I will go and vote for Mrs Le Pen.”