Explore Estonia: land of old believers, onions and chocolate box good looks

- Travelling south along the Russian border, from the rebuilt town of Narva to the capital Tallinn

- The beliefs of the starovery, who settled on Lake Peipsi’s shores, survive despite dwindling numbers

During World War II, Narva was contested by the Nazis and the Soviets. This northeastern Estonian town was one of the few places where the Germans halted the 1944 advance of the Red Army, delaying the Soviet victory for six months. Ninety-eight per cent of the town’s buildings were destroyed in the fighting. Today, almost 30 years after Estonian independence, 85 per cent of Narva’s population of 57,000 are ethnic Russians and more than one-third are Russian citizens.

Rebuilt in the 1970s, the town’s medieval Hermann Castle has ramparts that descend to the banks of the grey Narva River, which separates Estonia from Russia and from where it is possible to stare across the water to Ivangorod and a 15th-century fortress with Russian tricolour flags fluttering on its turrets.

Hermann Castle’s windswept main courtyard is watched over by the last statue of Vladimir Lenin standing in Estonia. The effigy of the Soviet Union’s first leader is 10 feet tall, right arm raised, defiant and eternal in bronze. It stood proudly in Narva town centre for 41 years before being removed in 1993, two years after Estonian independence. Narva’s mayor insisted the cable used to hoist Lenin from his pedestal should not be tied around his neck as a concession to local loyalists.

The drive south from Narva follows a border of fences and fields to Lake Peipsi, where marker buoys leave visitors in no doubt whereabouts in the water Russian territory begins. Tarmac turns to gravel as my car crunches through the small villages by the lake, following a route known locally as the Onion Road – no prizes for guessing what villagers grow in these chequerboard fields. The sun is out and locals have come to swim in Peipsi’s tideless water, pick raspberries in the surrounding forest and sweat in wood-burning saunas.

The villages along the Onion Road are home to the starovery, or “old believers”, whose ancestors broke from the Russian Orthodox Church and settled here 350 years ago. They refused to shave off their beards or wear Western clothes and sought out the shores of a lake big enough for full-immersion baptisms, as their religion demands. There are no more than 2,500 starovery left and the collapse of the Soviet Union and closing of borders means the road to Leningrad is no longer busy with the old believers’ onion trucks.

About a quarter of the way down Lake Peipsi is Kallaste, the largest starovery settlement since 1720. Its broad-faced women wear flowered shawls, pinned under the chin rather than knotted because the knot is symbolic of Judas’ suicide by hanging. The scarves are the only splash of colour in a functional workaday uniform of dark skirts and black rubber boots. Some older women wear a belt at all times, as a form of protection against the devil, I’m told, taking it off only in the sauna.

The yellow wooden church in nearby Kolkja is the centre of this village community and as I stand at the back (there are rarely seats in an Orthodox church) and listen to a service whose words and liturgy are unintelligible to me, I am moved by a simple event that has been rehearsed for hundreds of years.Its permanence belies the shrinking numbers of starovery by the lake.

The congregation consists mostly of women bundled up in layers of clothing, scarves pinned beneath chins (or in some cases, several chins), standing on the left of the church and crossing themselves with two fingers before candlelit icons. They all kiss a framed icon as they enter the church and occasionally a small bearded man in black emerges from the shadows to wipe the smears from the glass.

A small choir lurches into chants that can hardly be cast as hymns, the quivering voices filling the darkness of a room lit only by beeswax candles despite the gloom outside. Old believers scorn clamour and ostentation, so there is no bell ringing, though acrid incense issuing from brass burners fills the room and there is a hint of Byzantine extravagance in the heavy brass chandelier that hangs from the oak beams and the pendulous gold cross that swings from the priest’s neck. It parts a rift in his beard as he bends to place a ringed hand on headscarves and blesses his supplicants.

The cemetery outside, amid aspens, evergreens and birch, is no less burdened with symbolism. A fine Peipsi mist settles on the grave markers: traditional Orthodox crosses with twin diagonal bars, inscribed at the top with the names of the deceased next to their photograph.Some have been knocked flat, others are overgrown; some have congregated in conspiratorial huddles and others are isolated, surrounded by gaps of grass, where other markers might once have been. The chaos seems illustrative of the fight for the survival of the old beliefs, neither Russian nor Estonian, on the shores of this frigid lake.

Estonia’s capital, Tallinn, has never been razed or pillaged, unlike so much of the Baltic states, and the medieval old town has retained its ancient charm. Neglected by the Bolsheviks as unworthy of modern communism, the city has been restored to a technicolour chocolate-box prettiness (Tallinn became a Unesco world cultural heritage site in 1997) in a way that Narva and starovery communities could never be. Businesses in the old town require their staff to dress like medieval peasants lest anything spoil the experience for tourists.

The Estonian tricolour flies again over Toompea Castle, near the old town, although even in this modern and independent Tallinn, where cruise ships disgorge their summer loads to scour the old town alleyways and buy things they don’t need, the shadow of repression is never far away.

Patarei, a fortress built in 1840 by Nicholas I of Russia to protect the sea route into St Petersburg, served as a prison in Soviet times. The big stone building is being converted into a museum but for now remains a derelict, evil-looking edifice behind barbed wire, incongruous in its setting so close to the old town and the sailing boats on Tallinn’s harbour.

More enlightening are the downtown Museum of Occupations and Freedom (plural because it covers both Soviet and Nazi periods) and the former KGB building, its basement windows bricked up to prevent the sound of interrogations and torture from reaching passers-by on Pikk Street. Estonians referred to this “headquarters of the organ of repression of the Soviet occupational power” with gallows humour as “the tallest building in the country”: even from the basement you could see Siberia.

The actual tallest building in Tallinn is next door. At 159 metres, the Gothic spire of St Olaf’s churchmay have been taller than anything else built by man when it was erected, at the end of the 15th century. I see white flecks of water and boats leaning into the breeze on the Baltic Sea from the observation deck below the spire, from where, it is said, the architect fell to his death. Legend has it that, as his lifeless form lay on the street below, a toad and a snake emerged from his jaws.

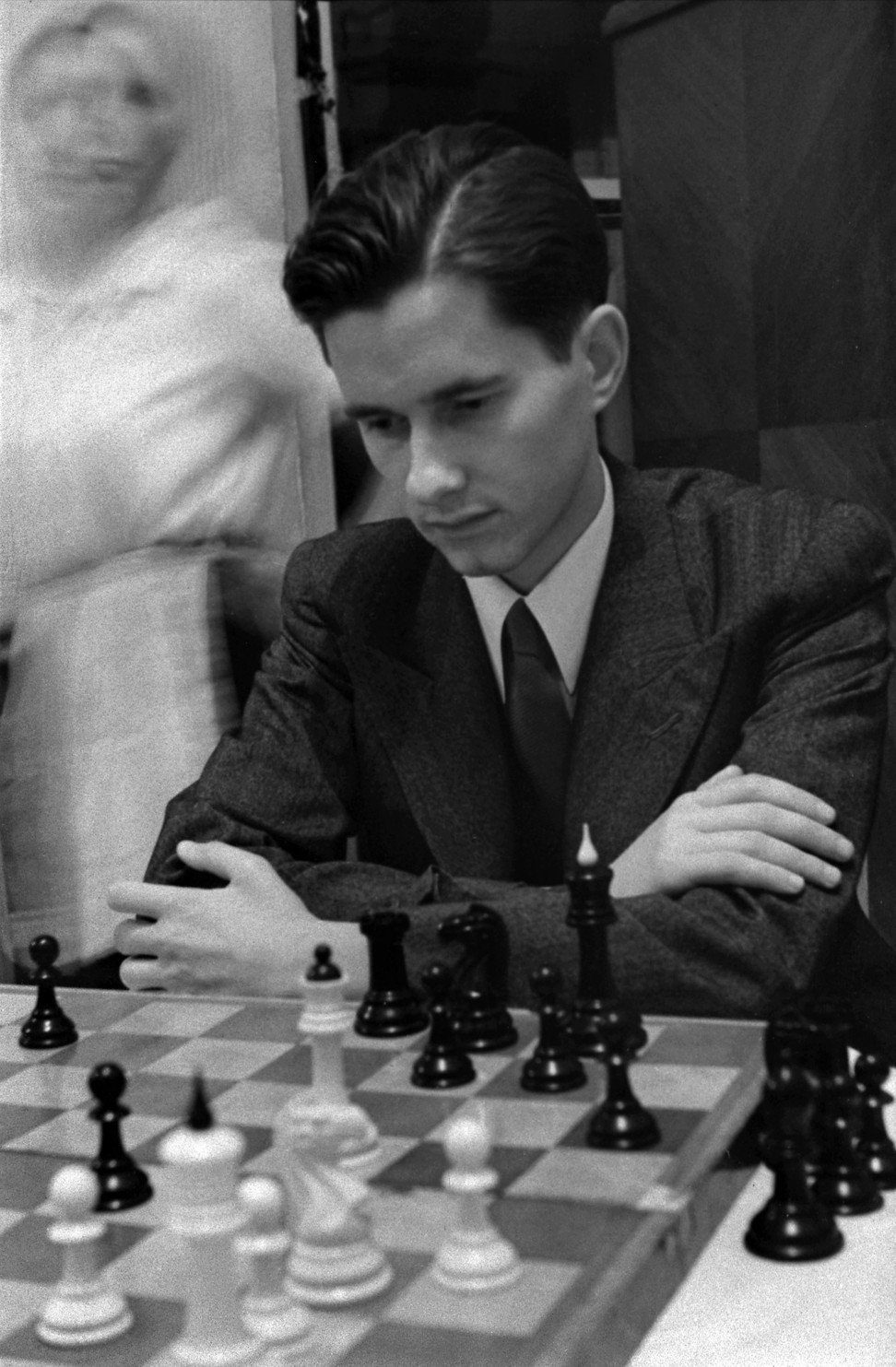

Estonia is a nation of contradictions. Its people love the outdoors but 100,000 attended the 1975 funeral of chess player Paul Keres, who they subsequently voted “sportsman of the century”. It’s a country of starovery but was also the least religious nation on Earth in 2009, according to a Gallup poll (although that award now goes to China).

As I look back from the Helsinki ferry (the Finnish capital is a 2½-hour ride from Tallinn) towards St Olaf’s spire, I decide I will return. I have become something of an old believer in Estonia, too.