Five independent champagne producers show there’s more to life than Moët & Chandon and Dom Pérignon

- France’s Champagne region is home to thousands of ‘secret’ independent winemakers happy to welcome those thirsty for something different

- Fallet Dart’s cellar holds one million bottles, Gilles Mansard produces brut, rosé, and blanc de blancs, and wine has been made at Champagne Aspasie since 1794

Champagne may rank as one of life’s ultimate luxuries but the choice for many buyers outside France is often limited to the renowned brands, which are known as the grandes maisons: Dom Pérignon, Ruinart, Moët & Chandon, Bollinger, Perrier-Jouët.

Yet for the French, there is a strong tradition of discovering your own champagne producer; an independent vigneron that you may have visited while touring Champagne’s vineyards or discovered at a winemaker stand at a seasonal gourmet fair, perhaps while stocking up for Christmas and New Year.

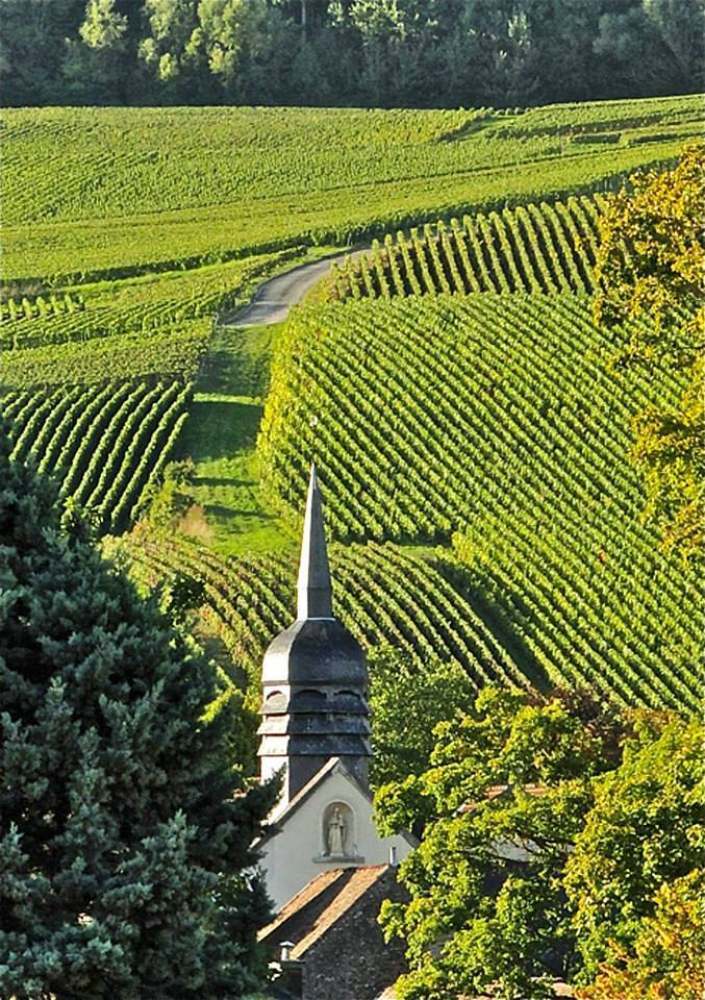

Chance encounters make for loyal customers, whose friends may later be permitted to order from these “secret” bubbly suppliers. Maybe the new converts will themselves travel to Champagne, to visit the cellar of their new favourite vigneron; the region, whose “hillsides, houses and cellars” are on Unesco’s World Heritage List, is spectacular throughout the year, from spring, when buds hang from the vines, through to harvest time, with its autumn colours, and winter, with its snow-dusted landscapes.

There are thousands of independent winemakers across Champagne, producing their own vintages while crucially selling part of the harvest to the grandes maisons. Some, though, are waking up to the possibility of exporting their own product, especially since the boom in online shopping brought about by the pandemic began.

Here are five vignerons ready to dispatch a courier with a case of their bubbly to a curious Hong Kong champagne lover. And who knows, perhaps that customer may wish to visit when travel is a realistic possibility again.

Champagne Fallet Dart

Just 40km outside Paris, the A4 autoroute exit towards the Marne River immediately heads into champagne country, with rolling hills suddenly covered in vineyards, and quaint signs proposing wine tastings displayed outside almost every village house.

Paul Fallet is the proud 17th generation of a family that has been making wine here since 1610. His ancient stone farmhouse is surrounded by a 24-hectare vineyard, and everywhere Fallet goes, his faithful dog, Otis, follows.

Visitors to the estate are warmly welcomed with a free tasting and a cellar tour that explains the complexities of champagne production.

“Our family historically sold our grape harvest to the village wine cooperative, but in 1972, my father made the decision that we should finally make our own champagne, meaning a huge investment to create a cellar,” Fallet says. “This meant we became officially récoltant manipulant, the champagne term for an independent vigneron who can both make his own champagne and sell grapes to the likes of Veuve Clicquot, Mumm and Pommery.

“From the first, we decided never to sell any of our harvest, choosing to make quality wines and valorise our work in the vineyard and cellar.”

A cellar that holds a staggering one million bottles allows Fallet to sell both a classic range of blended, non-vintage champagnes and a premium line – the Collection Privée – from which wine buffs can choose champagne from a specific year.

Domaine Bonnaire & Clouet

Just a short drive from Épernay, the unofficial capital of Champagne, the entrance to the commune of Cramant is marked by a fitting statue: a towering bottle of bubbly.

Here, the modern cellar of Bonnaire & Clouet differs from its neighbours, as this domaine represents two very different estates. It was created upon the marriage of the parents of young winemakers Jean-Emmanuel and Jean-Etienne Bonnaire. Both vineyards are prestigious grands crus, one in the Bouzy commune, in the Côtes des Noirs, an area famed for its pinot noir grapes, the other in Cramant, the heart of the Côtes des Blancs, where chardonnay is the star.

“Right now the demand [for champagne] is stratospheric, like a meteor that we can barely keep up with,” Jean-Emmanuel says. “And I think the pandemic has changed the way people drink champagne. Instead of occasionally ordering for parties, weddings, festivities, people were stuck at home and started to enjoy champagne all year round, as we do here in the vineyards, where it is an aperitif but also a wine to be paired during meals.”

The Bonnaires offer free cellar tastings and run the B&B Les Barbotines, in Bouzy.

“Our family has always followed the philosophy of wine tourism as a duty to share our passion, the fruits of our work,” says Jean-Emmanuel. “My mother, Marie-Thérèse, still looks after the B&B, decorating the four rustic rooms and looking after breakfast, while visitors get the experience of staying in an authentic 19th century vigneron’s manor house, with tastings in the garden or below, in the cellar.”

Champagne Gilles Mansard

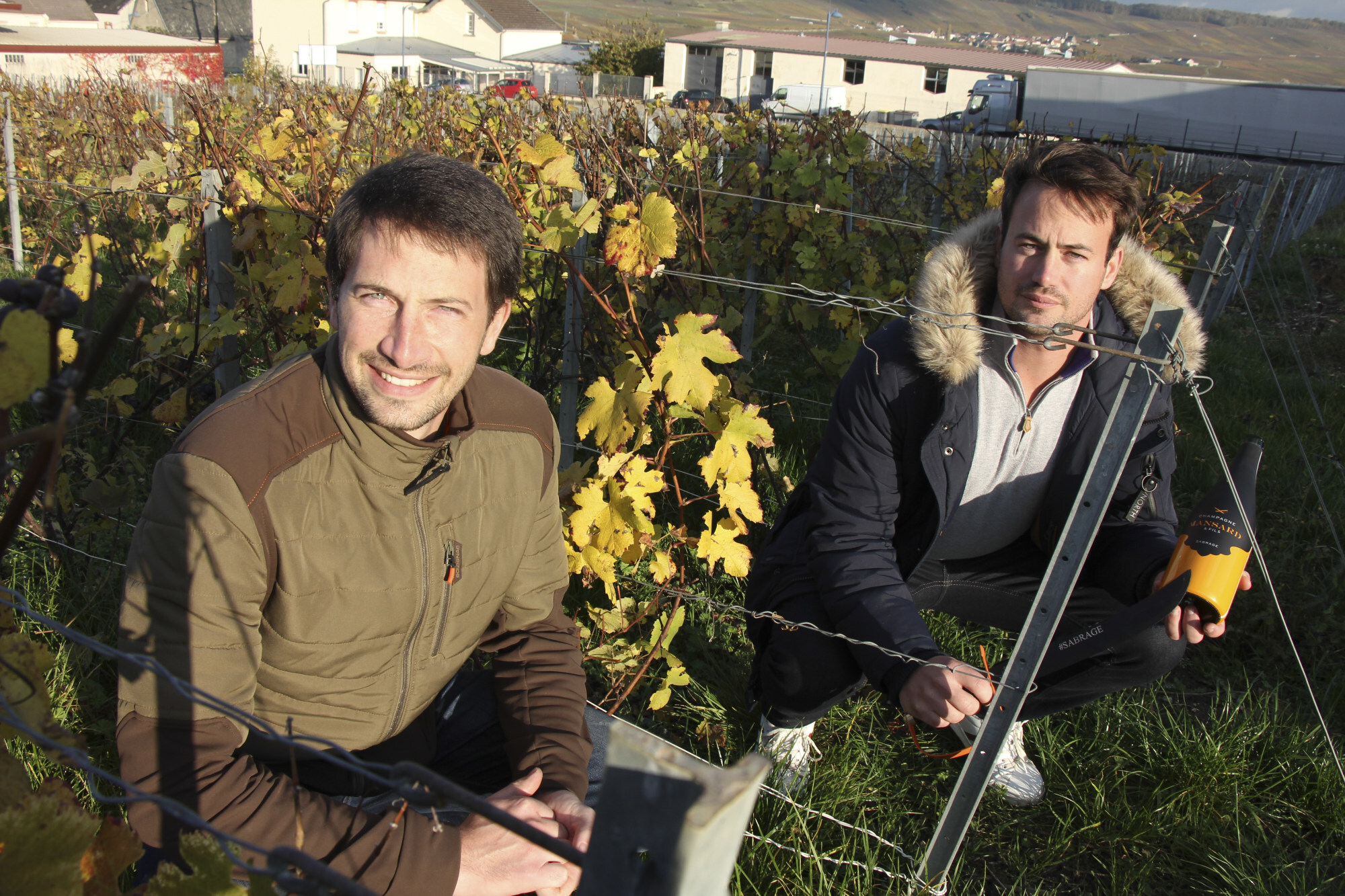

Maxime and Vincent Mansard are brothers in their early 30s who are breathing new life into their family winery. Their great-great-grandfather, Benoni Mansard, was a pioneer récoltant manipulant, producing and bottling champagne some 120 years ago.

The Mansard cellar is located in the sleepy hamlet of Cerseuil, the grand 12th century church of which is surrounded by sturdy stone cottages whose inhabitants work mostly in the surrounding vineyards. Although the brothers’ estate amounts to just 24 hectares, it is divided into a complex patchwork of 71 parcels, stretching across 10 villages.

“But as this is the first year we are taking over the family business, for the moment we make our own champagne from just the best five, six hectares, producing around 60,000 bottles, and sell the rest of the harvest to the grandes maisons,” Maxime says.

Apart from producing a classic range of brut, rosé and blanc de blancs, the brothers are breaking new ground. Next year, they will commercialise a high-quality clos (made from vines grown in a wall-enclosed plot), using grapes from the heart of Cerseuil.

And they have just launched a case containing a stylish orange and black champagne bottle alongside a fearsome-looking sabrage blade – the only producer in Champagne to offer such an option – giving an invitation to drinkers to flamboyantly sabre the top off the bottle.

Champagne Jean Sélèque

In the same picturesque village as Château de la Marquetterie and Château de Pierry, both of which date back to the 18th century and host luxury champagne events, Nathalie Sélèque welcomes visitors to her far more down-to-earth tasting room.

Hers resembles a garage art gallery and also exhibits the colourful abstract paintings of her late father, Jean. She is as effervescent as her champagne, popping open bottles from 10 cuvées, sipping but savouring the bubbly rather than spitting, as she recounts the complex history of her winery.

Sélèque was the science teacher at the local school before becoming a vigneronne, but in a complex inheritance struggle – not uncommon in winemaking regions – she lost her father’s cellar yet kept the family’s four hectares of vines, including highly prized premier cru plots around the commune of Pierry.

Officially, therefore, she is a récoltante coopératrice, meaning she cultivates and harvests the grapes but then works with the local wine cooperative, which produces her champagne and stores it for ageing. However, it is Sélèque who decides on the blends that become her cuvées.

She has a lucrative contract selling part of her harvest to Bollinger, James Bond’s favourite label, which has been spotted in almost every 007 movie since Live and Let Die (1973).

Pierry’s vineyards are all classified as premier cru, so, with 1,200 inhabitants, it is livelier than many of the surrounding small villages and abundant with winemaker cellars, boutiques and cafes.

Before church property was confiscated during the French revolution (1789-99), much of Pierry was owned by a nearby abbey, with Benedictine monks based here at the same time as Dom Pérignon was discovering how to make champagne in Hautvillers, 9km to the north.

Champagne Aspasie

In the village of Ville-Dommange, Paul Ariston sips a flute of his own champagne in the classic rural bistro Coq et Vins – where a typical three-course lunch of fricassee of escargots with leeks, braised pork belly and curly cabbage, and apple tart smothered with almonds goes for €23 (US$26).

“Even with a GPS it is not easy to find our hamlet of Brouillet and its 75 inhabitants,” he says. “But for us it is the centre of the world, although the cathedral city of Rheims and all the grand champagne houses are just 25km away.”

Ariston lives in a 400-year-old farmhouse within which the family has made wine since 1794. He declares himself an artisan vigneron and, cultivating a 12-hectare vineyard, he is that rare winegrower who grows and blends all seven grape varieties allowed under the champagne designation, including the rare arbane. He is another independent récoltant manipulant who refuses to sell any of his harvest to champagne houses.

A further surprise here is the visible biodiversity.

“The farm actually covers 100 hectares, with woods, pastures and farmland, as I continue to grow wheat, barley and alfalfa,” Ariston says. “I won’t give up my agricultural roots even though sometimes I think I am still stuck in the Middle Ages.

“But I love making champagne and that is crucial to our family’s financial independence. And next year will be our first as officially certified organic.”